Thomas C. Fleming, 91, is the nation's oldest and longest-running black journalist. The co-founder in 1944 of the Sun-Reporter, Northern California's largest weekly African-American newspaper, he continues to write two articles a week for the paper from his home, in addition to his syndicated column, "Reflections on Black History." The column is distributed by the National Newspaper Publishers Association and sent to more than 200 African-American newspapers nationwide.

In 1926, after graduating from Chico High School, Fleming began his career as a bellhop for the Admiral Line, then spent five years as a cook for the Southern Pacific Railroad. He entered journalism in the early 1930s as an unpaid writer for the Spokesman, a progressive black paper in San Francisco. In 1932, at the height of the Great Depression, he returned to Chico as a political science major at Chico State College, completing three semesters before returning to the San Francisco Bay Area in 1934.

In 1944 he was hired as founding editor of the Reporter, which later merged with another black paper, the Sun, to become the Sun-Reporter. For almost 50 years, the Sun-Reporter was published by Fleming's closest friend, the late Dr. Carlton Goodlett.

In July 1997, Fleming retired as executive editor of the Sun-Reporter to concentrate on his memoirs, which have appeared so far in more than 60 weekly installments as "Reflections on Black History." The column is written in collaboration with Max Millard, a former copy editor and staff writer for the Sun-Reporter, who interviews Fleming on tape, blends the words with Fleming's writings, then fact-checks the result. The complete columns to date can be found on Fleming's web page in the Free Press.

On his 90th birthday in 1997, Fleming self-published his first book, a 48-page collection of stories and photos from his early boyhood in Jacksonville and Harlem. On his 91st birthday, he published "Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934," co-authored by Michele Shover, a professor of political science at California State University, Chico.

A lifelong bachelor who lives alone, Thomas Fleming is the 1997 winner of the Career Achievement Award for Print from the Northern California Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.

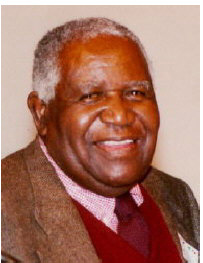

SAN FRANCISCO -- In July 1997, at age 89, Thomas C. Fleming retired as the executive editor of Reporter Publishing Company, Northern California's leading chain of African American newspapers.

The city's oldest and longest-running journalist, Fleming increased his output in September 1997 by launching a new weekly column on the Internet, "Reflections on Black History." It is posted on websites around the country and distributed by the National Newspaper Publishers Association to more than 200 African American newspapers.

Fleming is still the Sun-Reporter's most prolific writer, totaling about 2500 words a week -- the lead editorial, the "Weekly Report," which concentrates on human rights issues, and a black history column with a San Francisco focus.

On November 13, 1997, Fleming was honored with the Career Achievement Award for Print from the Northern California Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, receiving a prolonged standing ovation from an audience of 300.

Nearly as large a crowd attended his 90th birthday party on November 29, where the keynote speaker was San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, whom Fleming has known for over 40 years. When Brown first ran for public office in 1962, the only newspaper to give him front-page coverage week after week was the Sun-Reporter. Although Brown lost that first race, he won in his next attempt for the California Assembly in 1964, and has remained in office ever since. Brown has always credited the Sun-Reporter for jump-starting his career.

Fleming's "Reflections on Black History" is also being self-published in book form, as each section is completed. Part One, covering the years 1907-16, tells of Fleming's experiences in Florida and Harlem, with his eyewitness accounts of the history unfolding before him. A schoolmate of Fats Waller, he describes watching Marcus Garvey lead parades, and the black troops marching through Harlem on their way to fight in World War I.

Gifted with a prodigious memory, Fleming has been brushing shoulders with history for most of his life. Out of the 100 most significant African Americans of all time, as described in Columbus Salley's 1993 book, The Black 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential African Americans, Past and Present, Fleming has met 45, including Martin Luther King Jr., W.E.B. DuBois, Charles Houston, Thurgood Marshall, Malcolm X, Paul Robeson, A. Philip Randolph, Langston Hughes, Mary McLeod Bethune and Duke Ellington. Some, such as Robeson, became personal friends.

Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Fleming moved to Chico, California in 1919, graduated from Chico High School in 1926, and that summer moved to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he began his career by working as a bellhop for the Admiral Line and for the Southern Pacific Railroad.

The founding editor of the Reporter newspaper in 1944, then San Francisco's only black paper, Fleming remained as its editor when it merged several years later with the Sun to form the Sun-Reporter. He has been writing for it ever since. Over the past 54 years, his only absence from its pages was during a seven-month span in 1945, when he served in the U.S. Army.

A lifelong bachelor who lives alone, Fleming starts each day with exercise, cooks all his own meals, walks without a cane and reads four newspapers a day to keep abreast of the news.

In a visit to his crowded, somewhat cluttered San Francisco apartment, surrounded by his beloved history books and jazz collection, Fleming revealed that he didn't originally plan on a newspaper career, because no daily paper in the Bay Area hired a full-time black reporter until 1962. Then Ben Williams got the nod from the Examiner -- thanks to a recommendation from Tom Fleming.

Fleming plunged into community journalism in the late 1920s as an unpaid writer for the Spokesman, a black paper that supported the general strike of 1934, which shut down waterfronts all over the West Coast.

"We were aware of what working conditions were on the waterfront before the strike was called," Fleming said in his resonant, musical voice. "Blacks could only work on two piers in San Francisco. The rest of them -- if you even went near them, you might get beat up by the hoodlums. And there were only two shipping lines that you could ship out to work on.

"During the strike, there were some vigilante groups patrolling the entire Bay Area. . . . Apparently they were displeased with some of the editorials we were writing, because we came to work one morning and all the plate glass windows were smashed out. They had gotten inside and smashed the keys on the keyboard of our linotype machine, and they pasted up a note: `You niggers go back to Africa.'"

The paper went out of business soon afterward, but Fleming kept his hand in journalism by hosting a radio show, "Negroes in the News," and writing a column for the Oakland Tribune, "Activities Among Negroes."

His real break came in June 1944, when a "chance meeting with a guy on the street" led him to an interview with Frank Logan, a local black businessman who was planning to launch the Reporter and needed an editor. Fleming was his man.

"Blacks were up in arms about the hiring practices in the shipyards and other war industries," Fleming recalled. "And the Key System, which operated the transit system in Oakland, would not hire any black bus drivers or streetcar operators. . . . so I started writing editorials saying that if blacks could drive those big army rigs, they could drive those buses on the street too. They were demonstrating in front of the Key System's office, carrying placards denouncing Jim Crow practices in hiring. So apparently somebody with them started reading our paper, because the first thing I knew, I received greetings from my draft board."

Although he was the sole supporter of his invalid mother, and two years over the draft age limit of 35, Fleming's deferments were cancelled. A woman at the draft board told him in confidence, "They don't like those editorials you're writing."

Fleming's best friend, dating back to 1935, was Carlton Goodlett, who, at Fleming's urging, moved to San Francisco in 1945 after completing medical school, and set up an office near the Reporter. Dr. Goodlett's soon-flourishing medical practice allowed him to invest in the paper. Then one night, in a poker game, Goodlett won the newer Sun newspaper from its owner, a white businessman, and combined the two.

By the early 1950s, Goodlett had become the Sun-Reporter's publisher, a platform he used to become one of the most influential civil rights activists in San Francisco's history.

In the decades that followed, up until Goodlett's retirement in 1994, he and Fleming took turns writing the newspaper's editorials. Noted Fleming: "He never told me what to write and I never told him what to write."

Goodlett died in 1997, and was honored by having the block in front of City Hall officially renamed 1 Carlton Goodlett Place.

During the 1960s, the Sun-Reporter acquired the California Voice, an Oakland-based black paper, and launched seven weekly Metro Reporter newspapers, which expanded the Sun-Reporter's reach throughout Northern California.

Fleming estimates that over the years, his output has been 2000 to 3000 words a week, or about seven million words in print. In his career, he has attended nine national political conventions, met two presidents and gotten to know most of the leading political figures of California.

"The paper has always been committed to civil rights and complete equality," he explained. "I think that's been the primary goal of the black press. It was our stated goal to attain first-class citizenship, and to be a watchdog for whatever injustices based on racism occurred -- to let the world know about it.

"I felt that blacks had to have an editorial voice. And I think that's why black papers are in existence all over the country. If the white papers covered all the different facets of black society the way they do white society, there wouldn't be a black paper in existence."

In the Sun-Reporter's old building in the Fillmore District, a few blocks from Fleming's apartment, Fleming arrived every afternoon, holding court in the downstairs office, greeting people as they entered, reading his papers and receiving many phone calls and visitors. But in 1997, when the newspaper moved across town to the Bayview District, now the city's largest African American neighborhood, Fleming realized it was time to retire.

Asked whether he had achieved everything he expected out of journalism, Fleming responded with no regret: "I guess I did, with the exception of the pay level. But I was a good soldier. I was more interested in accomplishing one of my goals -- to see that we had a black newspaper here in San Francisco. I never did think about the income as much as other people might have thought. Because my needs were very simple, because I lived alone, and as long as I could take care of my personal needs, and purchase all these books through the years, and the records and things like that, that's about all I wanted out of life."