|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 34 |

Ships of the World

by Thomas C. Fleming, May 13, 1998 On my second day as a crew member of the S.S. Emma Alexander in 1926, fog closed in on the ocean and the foghorns were heard with their mournful tones as they continued their systematic dirge, warning ships that danger was near the shore. A waiter told me that the foghorns were baby whales crying because they had lost their mother, and that I was to throw crackers into the ocean to feed the unhappy baby whale that was following the ship, because it thought the ship was its mother. Two other waiters standing near began to laugh loudly when I walked to the ship's railing and peered into the ocean, searching for the lost baby. I caught on that it was a joke, and felt quite sheepish. I found out they told that to everybody who first came to work on the ship. The stewards crew was called about 6 o'clock in the morning. The cooks and bakers had been up since 5 and were busy preparing the breakfast. Some passengers rang for coffee, and others paced the decks looking out at sky and water. The ships went far enough out to sea that the coastline was invisible.

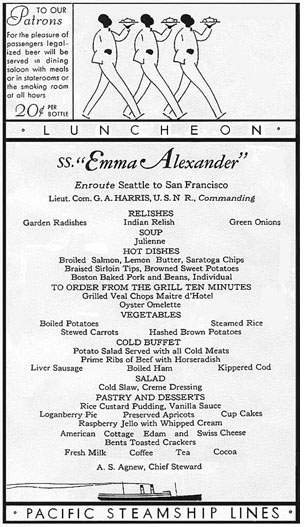

Menu for the S.S. Emma Alexander, circa 1920s. Entering San Francisco Bay from the sea was a different view than was presented when I left on the Emma for the northward trip. The Emma had to slow down outside the Golden Gate for the harbor pilot to board the ship. His duty was to steer the ship through the many channels and currents of the bay. As the ship slowly entered the harbor, I noted the names of shipping companies painted on the piers facing the water. The harbor was filled with ships of all dimensions -- huge freighters that sailed to all corners of the world, and passenger vessels that in some instances were even bigger. Ships loaded and unloaded cargo before resuming their voyages for ports everywhere. The Embarcadero was busy, with the ferries and the huge maritime trade that sailed to San Francisco, including the ships that plied the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers. The Union Line was an Australian company which operated large passenger liners between Australia and the United States. The British had passenger liners that sailed around the world, called the Peninsula and Orient Line. A Japanese shipping company was very prominent; it had a lot of luxury liners on the Pacific coast. There were also passenger ships of the Holland American Line and the Scandinavian Line. Most of the ships flying foreign flags were staffed by Asians in all departments outside of the officers. They were non-union, and the crewmen made the ships their homes until they retired with enough money to make them very important people in their hometowns in Asia. The Dollar Line -- very big, round-the-world ships -- was headquartered in San Francisco, and carried a large amount of cargo and passengers. Then there was the Matson Line -- American flagships which sailed between San Francisco, Los Angeles and Honolulu. There was a lot of work on the waterfront, but despite this huge traffic of cargo and freight, blacks were very conspicuous by their absence. Black longshoremen were barred from all but two piers in San Francisco -- the Panama Pacific and the Luckenbach Line piers. Both companies had their headquarters in New York City. The Luckenbach ships were primarily big cargo carriers that had accommodations for about 50 passengers. The Luckenbach Line served ports in South America, both on the Pacific and Atlantic coast. The Panama Pacific had two large passenger ships, the Pennsylvania and the Virginia, which plied the seas from New York City. They sailed down the coast to the Panama Canal and were navigated through the canal to the Pacific Ocean. Then they would make the run to Los Angeles, where they would stop and discharge passengers and cargo, then end their voyage at the Pacific Coast terminal for the company, in San Francisco. The stewards crew on the Panama Pacific Line was all black. The Matson Line and the Dollar Line didn't hire black people, even for stewards. They had mostly Asians in their stewards department. Like other ships flying the American flag, they received considerable subsidies from the government for carrying the U.S. mail. The U.S. Army operated large troop transports that called at New York and other East Coast ports, then through the Panama Canal to San Francisco, Honolulu, Manila, Hong Kong and Shanghai. They carried American service personnel and their families to the army posts in Hawaii, the Philippines and China. The army transport service hired blacks in their stewards crews. These jobs on the Army vessels were sought for diligently by seamen, because the pay was good and the ships touched so many ports.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Fleming. Email. At 90, Fleming continues to write each week for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. A 48-page book of his stories and photos from 1907-19 is available for $3, including postage. Send mailing address.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |