Reflections

on

Black

History

______Part 39 |

The Southern Pacific

by Thomas C. Fleming, Jun 17, 1998

It was the last days of June 1927 when I arrived back in Oakland, California to try to find work on the railroads. I was helping my mother and my sister Kate, because I had the biggest job in the family for the first three years when we moved down to the San Francisco Bay Area. I was just 19, but in reality I was the head of the house. I gave my mother most of what I earned, because I knew she had a house to run.

Mama had rented an apartment on 8th Street which had one room and a kitchen. There was a community bathroom which we shared with two other tenants. Mama and Kate slept in the room, and for several months I slept on a pad in the kitchen, until my earnings made it possible for us to move to a house in Berkeley.

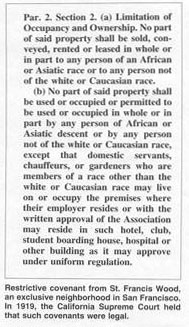

Photo and caption of a restrictive

covenant from San Francisco.

There were certain areas in Oakland, San Francisco and other cities nationwide where black people could not live because of restrictive covenants. The property owners all signed an agreement that they wouldn't sell to anyone who wasn't white; it was used against Asians too. It had been challenged in the courts, but in 1919 the California Supreme Court had ruled that restrictive covenants were legal.

There were certain areas in Oakland, San Francisco and other cities nationwide where black people could not live because of restrictive covenants. The property owners all signed an agreement that they wouldn't sell to anyone who wasn't white; it was used against Asians too. It had been challenged in the courts, but in 1919 the California Supreme Court had ruled that restrictive covenants were legal.

In the 1920s, there was an area of East Oakland called the English Village where they wouldn't sell to blacks, but one of the cooks I would soon work with, Bourbon Thomas, got a white real estate man to buy a house there and transfer the deed to him, so he was able to live there. That was fairly common.

In San Leandro, right next to Oakland, I don't know if they had covenants, but you weren't welcome: nobody would sell to you. There was a lot of hostility directed against blacks by what was largely a Portuguese community there. I think it was based more on language than anything else, because many of the Portuguese speakers came from the Cape Verde Islands and were brown-skinned or black themselves.

When you talk about railroads in California, you can only speak of the Southern Pacific. It was the biggest property owner in the state. They were the big bad boys in California, and they dominated the state legislature. When Hiram Johnson was elected governor in 1910, he went to Sacramento to fight the monopoly that the Southern Pacific held over the state capital. He fought them all the way, and managed to stop some of the things they were getting away with.

In 1927, the Southern Pacific had a large terminal in Oakland. It put on a lot of extra cars in the summer to handle the traveling American public, and the Pullman Company added more sleeping cars, club cars and observation cars, which meant bigger train crews.

I went to the Southern Pacific commissary in West Oakland and asked if there were any openings. The man at the dispatcher's window said no, but told me to stick around and wrote my name in a pad. There were quite a number of other black men, some of them students, waiting around the commissary to see if they would be hired. Most of the dining car crew were black, but a few were white.

I stayed until four o'clock that day, and for two more days, when the dispatcher came out and asked if I wanted a job as fourth cook. I answered yes. He signed me up and told me the number of the dining car, which was in the railroad yard, stocking up in preparation for a trip to Los Angeles the next morning.

My father had been a cook, and I came down to Oakland to be a cook. I didn't want to be a waiter, because learning to be a cook, you'd get jobs in other places more quickly than a waiter could.

The Southern Pacific also hired blacks as porters and maintenance workers at the terminals. And a few blacks worked as clerks at the company's headquarters on Market Street in San Francisco.

There were two black supervisors on the dining car crews -- Henderson Davis, who was titled traveling chef, and Max Hall, the traveling headwaiter. These two men would travel over the Southern Pacific system as far east as Ogden, Utah. Their job was to inspect the work of the crews and see that the kitchen, dining room and pantry were always clean and in order.

If we were traveling south, the northbound train would pass us at a certain point every day. If there was an inspection that day, one of us would signal that the inspector was up or down the road, so there would be a frenzied period of getting things in order.

Allan Pollak, the general manager of the railroad's dining car service, would frequently leave his San Francisco office and travel all over the whole system on inspection.

I can recall one time when Pollak was on the car at the same time that Henderson Davis and Max Hall were there. Davis and Hall did what the crew called a great Uncle Tom act, and were very caustic in their comments to the crew. We knew they were just trying to impress their boss.

I worked for the Southern Pacific for almost five years. I didn't think the company would ever be sold, as big as it was. But there's no Southern Pacific any longer. Union Pacific bought it out in 1996, and the merged company hauls only freight. Amtrak, which is subsidized by the federal government, was formed in 1971, and since then, it has operated almost all the passenger trains in America.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Fleming. Email.

At 90, Fleming continues to write each week for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. A 48-page book of his stories and photos from 1907-19 is available for $3, including postage, and a 90-minute cassette tape of his recollections of black life in Florida, Harlem and Chico from 1912-1926 is available for $5, including postage. Send mailing address or call 415-771-6279.

Fleming Biography

More Fleming articles

Back to Front Page

|