Reflections

on

Black

History

______Part 53 |

Deadheading to Portland

by Thomas C. Fleming, Sep 23, 1998

Between 1927 and 1932, I worked for Aunt Mary. That was the nickname the black workers gave to the Southern Pacific Railroad. I never heard a white person use that term. The company was like our aunt -- that's what we meant. Aunt Mary took care of us, provided our living and gave us jobs.

At that time, the Southern Pacific was still the biggest private landowner in California. All over the country, the railroads and ships had a monopoly in hauling freight, passengers and mail for long distances. Every rail company had a contract with the government for carrying the mail, and ships flying the American flag got a payment from the government if they carried even one letter.

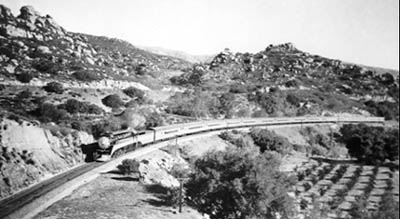

Southern Pacific's "Daylight" train, which ran between San Francisco

and Los Angeles, featured some of the most spectacular views of any

railroad line in the nation. (Photo circa 1940, courtesy of Bill Yenne.)

Many rail companies got their land from the federal government in the 19th century, in the form of land grants. After they raised enough money, they went go to the government, and it granted them the right to build a rail line. The government wanted to develop the country, so it would give the land away, and sometimes money too.

Many rail companies got their land from the federal government in the 19th century, in the form of land grants. After they raised enough money, they went go to the government, and it granted them the right to build a rail line. The government wanted to develop the country, so it would give the land away, and sometimes money too.

The government granted as much as 20 miles of land alongside the track, on one side at a time in a checkerboard pattern, so that the railroads wouldn't have exclusive control over the adjacent land. The railroads were responsible for most of the towns in California: they sold the land off, encouraging people to come out and settle. That happened all over the West.

The corporate headquarters of the Southern Pacific was in Louisville, Kentucky. Their tracks never touched anyplace in the state, but Kentucky had the lowest corporate tax of any state in the union. The company held its board meetings there -- that was all. A lot of big corporations did that in those days.

One night in 1928, instead of getting the regular three nights at home after arriving back in Oakland, we were given orders to return to the commissary the next morning to stock up the car immediately. Then we were told to remain on the cars, which would be leaving within a few hours, destination unknown. Not expecting to go out again right away, I did not have a razor, a change of underwear or an extra shirt.

A switch engine uncoupled our car and pulled it to another track, where the switching crew formed a train. Soon there were 12 dining cars, six club cars, and six observation cars all coupled together, each fully stocked. Then a big locomotive slowly pulled us out of the assembly yard.

We heard that the train would deadhead to Portland, Oregon with just the crews and no passengers. The railroad jargon "deadhead" means to go directly from one point to another, with no stops except to change the operational crew, who were always white men.

Almost everyone else on board -- the porters, cooks and waiters -- were black men. We had a full day and a half of travel, in which all we had to do was walk from one car to another exchanging gossip. We only had to prepare meals for the crews, which usually required just one cook. As the train rolled through Northern California, I spent most of the afternoon sitting on the platform of the last observation car of the long train, reading newspapers and watching the scenery. In one dining car, one of the biggest crap games I had ever seen was taking place among the crew members.

At Gerber, about 200 miles north of Oakland, the train halted long enough for a second locomotive to be added as a "helper hog," as we started climbing into the mountains. The engineer, fireman, conductor, and brakemen made their departure, and were replaced by another crew to operate the train. After the usual inspection of all of the cars, the train began to move for Mt. Shasta City, at the base of Mt. Shasta.

This was a regular stop of the Southern Pacific during daylight hours, when passengers would get off and drink the clear, naturally carbonated water from the springs. The kitchen crew always scooped up a gallon or so in some storage cans. It would be hot as hell in the kitchen, and you were glad when you could go out with one of those cans and fill it up with that ice-cold water. We added sugar to it, making the most delicious cream soda I have ever consumed.

A short time later, the train crossed over into Oregon, which I thought was very beautiful. Everything was so green; trees and other vegetation grew so lushly in that state. It was a remarkable contrast, because after June, just about everything in California turned brown, because there was so little rain, while in Oregon, it rains during the

summer months.

When the train reached Portland the next afternoon, new trains were made up, with Pullman sleeping cars, an observation car, club car, and two dining cars in each of the new formations. The trains filled up with Shriners, who were holding their national convention in Los Angeles that year.

The convention lasted four days, and because of a hotel shortage in L.A., some people remained on the trains, requiring the Pullman porters to work every day.

I got a view of Los Angeles from the area near the railroad yards, and saw a big sign standing on a hill near Glendale which read "Forest Lawn." The chef explained to me that it was the fancy burial grounds, where impressive funeral services were staged for the well-to-do. He emphasized that no blacks were ever buried there.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Fleming. Email.

At 90, Fleming continues to write each week for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. A 48-page book of his stories and photos from 1907-19 is available for $3, including postage, and a 90-minute cassette tape of his recollections of black life in Florida, Harlem and Chico from 1912-1926 is available for $5, including postage. Send mailing address or call 415-771-6279.

Fleming Biography

More Fleming articles

Back to Front Page

|