|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 75 |

Blacks and the labor movement

by Thomas C. Fleming, Apr 28, 1999 San Francisco always had a reputation of having a good liberal population, because one thing, it's always been a strong union town, whereas Los Angeles was what you'd call an open city, where you didn't have to belong to a union to work. The labor movement reached its height in the 1930s, when the Depression seemed to bring American industry to a halt. But even in San Francisco, most unions then excluded black workers. That color thing was very powerful. Up until the late 1800s, blacks had worked as cooks and waiters in some of the city's best restaurants. But when the restaurants began to unionize, they wouldn't accept blacks as members, and the black workers were replaced by whites. In order to be recognized by company owners, a union had to be a member of the American Federation of Labor. The biggest union in the AFL, then and now, was the Teamsters, who operated all commercial vehicles, including the ones on the docks. They were called teamsters because at one time, they all drove wagons pulled by teams of draft horses. When I first came to San Francisco in 1926, workhorses were still being used on the waterfront, pulling heavy freight wagons called drays, although they were rapidly being replaced by trucks. I don't think blacks were getting any Teamsters jobs them. The union was ruled by thugs and hoodlums, and plagued with leaders right out of the underworld. The United Mine Workers, which held a charter from the AFL, was one of the few trade unions that was truly integrated from its infancy. Its president, John L. Lewis -- perhaps one of the most able leaders in the history of the U.S. Labor movement -- early perceived the need for blacks to work alongside white workers. Lewis recognized that if blacks were left out, they would be used by owners whenever strikes were called in the industry, so the owners would not be compelled to sign any sort of labor contract with the union. Lewis had to convince the rank and file to bring blacks in: it was a matter of self-preservation. American industry in the 1930s was largely steam-operated, as electricity was still in the experimental stage as a power source. Coal had to be used in the steel mills, which were largely concentrated in states from the Atlantic coast to Illinois. Lewis and his lieutenants recruited heavily in the states of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Michigan and Minnesota. In the automobile industry, Henry Ford did not discriminate as much racially as General Motors, which itself was separate companies -- Chevrolet, Cadillac and Buick. Ford enjoyed some industrial peace initially, for he was the first of the big car makers to start paying $5 a day, and he got some stool pigeons to form what they call a company union in the Ford plant. It didn't belong to the AFL. When the Depression came, the auto workers union began to take shape under the able leadership of Walter Reuther, with stiff opposition by the owners. Reuther received moral support only from John L. Lewis. I'd put Reuther and Lewis in the same category as Harry Bridges, who headed the great waterfront strike in San Francisco in 1934. All of them welcomed black membership, and I think all were devoted to the cause of the working man. There were more strikes during the Depression than ever before. In the early 1930s, the sit-ins started in the Ford Motor plant and other big industrial plants. They closed whole auto factories in Detroit. The companies didn't meet the demands of the workers about raising wages and the number of hours to work, so most of the workers would go inside the plants and sit down, and stay in there for days. Henry Ford controlled his workers with the aid of Harry Bennett, who was head of security for the Ford empire. Bennett operated with the help of paid labor goons, who would beat and abuse Ford employees. I have a feeling that Hitler's Gestapo learned some techniques from Harry Bennett. Bennett made exclusive use of "Chowder Head" Cohen, an infamous strikebreaker, who scoured the gutters and alleys of big cities to recruit men noted for their brutality and sadism. "Chowder Head" worked anywhere in the nation where a strike was in progress. The National Labor Relations Act, also called the Wagner Act, was passed by Congress in 1935 to try to bring some labor peace. There was no such thing as collective bargaining until that act came in. Everybody wanted to get as much as they could for their labor, and of course the operators wanted to pay even less wages than they were paying before. That's where the conflict came from. The Wagner Act straightened a lot of that out, working to bring an agreement between employer and employees. The American Federation of Labor tolerated racial discrimination. I have never forgotten its lack of support of the Pullman porters union and the Dining Car Cooks and Waiters Union, which I joined in 1927, while working for the Southern Pacific Railroad. The black railway employees did not get their own charter from the AFL, but we were declared an auxiliary of the Bartenders Union. We paid dues and engaged in limited bargaining with the company, but had no voting rights. The Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters was finally granted a charter in 1937, becoming the first black union to be recognized by a major American corporation. But Philip Randolph was treated as some sort of pariah after the porters received their charter. Because he was the union's president, that placed him on the board of directors of the AFL. The heads of all the other internationals of the AFL were white men, and none of them would even speak to him.

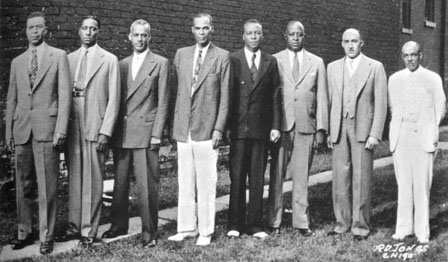

Officers of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters in the 1930s: (l. to r.) unknown, Bennie Smith, Ashley Totten, T.T. Patterson, A. Philip Randolph, Milton P. Webster, C.L. Dellums and E.J. Bradley. (Photo: courtesy of Chicago Historical Society.) William Green, the ultraconservative president of the AFL, had to persuade the Federation to grant Phil Randolph a charter, much against his own wishes. He disdained giving aid or comfort to Randolph. But some union leaders, including John L. Lewis, Walter Reuther, and Sidney Hillman, head of the garment workers union, had become disgusted with the almost lily-white practices of the AFL. In October 1935, they withdrew from the AFL and formed the Committee for Industrial Organization, or the CIO. Later it changed its name to Congress of Industrial Organizations. I shall never forget the historic wire that Lewis sent to Green. It had only one sentence: "Green, I disaffiliate." I don't know whether Green was racist himself. It was the membership that didn't want blacks in, and the leaders had to do what the rank and file wanted. But the CIO had almost as large a membership as the AFL, and it never did discriminate.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. This column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Fleming's 100-page book, Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934, is available for $7 plus $2 postage. Send request to tflemingsf@aol.com, or write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St #21, San Francisco CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |