|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 84 |

The National Negro Congress of 1936

by Thomas C. Fleming, Sep 22, 1999 Tarea Hall Pittman was one of the first civil rights leaders in Northern California to become well known outside of her home, Alameda County on the east side of San Francisco Bay. She was articulate and well-informed on most of the problems that confront all of us from day to day. Tarea hated the system of a double standard in race relations, and was always in the middle of fights that legitimately sought equality of opportunity. When the NAACP created district regional offices, Tarea was selected to be regional director for the West Coast, which seemed strange, since Los Angeles had by far the largest black population west of Kansas City. I first met Tarea in 1931, when she was already married to Dr. William Pittman, who had graduated from the University of California, then received a degree in dentistry from Meharry Medical School in Nashville, Tennessee, a black school. Blacks had some difficulties in gaining admission to any of the white dental or medical schools, primarily because of their visible pigmentation. Ty, as everyone called her, lived on Grove Street in Berkeley with two younger sisters, Faricita and June Hall. Ty was a Hall, the daughter of a pioneer black family that came to California in the days of the covered wagon. She was a native of Bakersfield in central California. Their father had purchased the Berkeley house when the family moved north. Tarea and her husband Bill were a little older than we were, but we mixed with them as equals. They were very progressive. The Pittman home was quite a gathering place for young black college students -- not only those who attended local schools, but students from all over the nation who might pay a visit to the Bay Area. Serious discussions went on all the time. Tarea had a razor-sharp mind, and was a tough opponent in debate. Bill was one of those black professionals who held out the helping hand to young blacks who were interested in furthering themselves. He was a practical joker. Bill always had lots of booze, but refrained from imbibing himself. When a party was in progress at the Pittman home, he would pour liberally, then have a glass of water for himself. When the subject showed the effects of the consumption, Bill would heckle him by shouting, "That cat can't take it," and laugh like hell. One frequent visitor to Tarea's home was Ishamel Flory. He was one of the young rebels, like me and John Pittman, founder of the Spokesman newspaper in San Francisco. Ishamel graduated from the University of California at Berkeley, then returned to Berkeley as a graduate student in the early 1930s, after his expulsion from Fisk University in Nashville for leading a student demonstration at the school. A young black man had been hanged by white folks, half a block from the campus, and the faculty was supposed to issue a report about it, but they didn't. Ishamel also protested against racism in the theater there; the black kids could only sit in what they called the buzzard's roost. The administration kicked him out and said he was a damn Red. I met Ishamel shortly after he arrived back in Berkeley, because he became active right away. Ishamel worked with C.L. Dellums, vice president of Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and he corresponded with leftists, both white and black, all over the nation. He had a great sense of social responsibility -- a terrific guy. Ishamel was the host of "Negroes in the News" on KWB in Oakland, the first non-music show on radio where blacks appeared on the air in the Bay Area. WB stood for Warner Brothers. That was the biggest electrical appliance store in Oakland, emphasizing radio and electric phonographs. The company got a license for a radio station. Ishamel went out there and worked out a deal to solicit ads, which would pay for his time on the air. He had to, because he had no money of his own. He managed to get a few small businesses over there, which brought in enough for him to do a half-hour broadcast every Sunday morning. The program covered everything about blacks in the United States. He performed the program until one Friday, he came by Tarea Hall Pittman's -- I happened to be there -- and informed me in her kitchen that I would have to take over the show, because he was leaving for Chicago in the morning. I said, "Man, I never even took speech or anything at school. I don't think I can handle it." He said, "I don't have anyone else." So Saturday I went out and bought the Chicago Defender and the Pittsburgh Courier and the Baltimore Afro-American, and started clipping out things, making up my program. When I went on the air, I didn't know know how to pace myself, and was still talking when the half hour was up. I did the program about five times before I finally informed Tarea that I could no longer do it. I knew there wasn't going to be any pay. Tarea took over herself, and had it for several years. Ishamel was a party to the formation of the National Negro Congress, which was founded at Howard University in 1935, and made a historic call to blacks all over the nation in the winter of 1935-36. Ishamel joined right away. There was a chapter in the East Bay, and Ishamel was the head of it. We usually met at Tarea's house. The first big meeting of the National Negro Congress was held in February 1936 in Chicago, since it was in the middle of the country, and the organizers felt it would be cheaper to attend than for everyone to come to New York. More than 800 attended the meeting, which lasted a few days. A lot of those blacks were liberal, and some were conservative, but they all knew what racism meant. Ishamel could not attend the meeting because of his other activities, but at least three blacks did go from the Bay Area -- C.L. Dellums, Louise Thompson Patterson, the radical who was married to the well-known black Communist, Bill Patterson, and Frances Albreyer, who was just a good housewife. Nobody had any money, but Frances said, "My husband is a Pullman porter. I can get a pass and go to Chicago by train. I won't have have to pay." From what I remember, the meeting was organized by two black men with the same surname, who were both Communists -- John P. Davis, an instructor at the West Virginia State College, an all-black school, and Ben Davis Jr., whose father was the leading black Republican in Atlanta. He handled whatever patronage the blacks got in Atlanta, so he was a very influential man. Ben Sr. was probably involved with illegal activities -- paying off the police to leave the gambling joints alone. His son didn't go for that. He sent his son to Harvard or Yale, and Ben Jr. became a Communist while he was up there. He never went back down South. A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, was elected president of the National Negro Congress. John P. Davis was elected executive secretary.

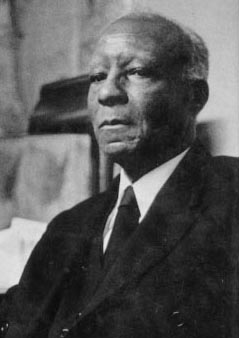

A. Philip Randolph, who was elected president of the National Negro Congress in 1936. A loose coalition of hundreds of black organizations, it was founded by religious, labor, civic, and fraternal leaders to fight racial discrimination, oppose the deportation of foreign-born blacks, and improve relations with blacks around the world. Tarea's sister Faricita Hall graduated from San Jose State College and was a captain in the U.S. Army during World War II, after going to Officer Candidate School. She became a teacher after the war, then an administrator. That's when they started opening up the doors to black teachers in California. Tarea's life changed even further as she became more and more active in the NAACP. She attended several national conventions, where she became very well acquainted with Walter White and Roy Wilkins, and also with Lester Granger and the other leaders of the National Urban League. Tarea didn't have any children. She never ran for office; no black person, male or female, had even tried to be elected to any office in Oakland or Berkeley then. But she had quite a big following in the whole Bay Area. I think she relished what she was doing. She worked with organizations of both sexes, with labor unions, and with all the liberal groups in the Bay Area. She saw social problems, and tried to do something about them. Ishamel went to live in Chicago in the late 1930s and stayed there. But he was still very noisy. He continued to speak out against social conditions there, that he felt needed improving. He never did lose his liberalism. At the time of this writing, he is living there still, at the age of 92.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. Produced exclusively for the Columbus Free Press, this column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Thomas Fleming's 48-page book of stories and photos about his boyhood in Harlem is available for $3 plus $1 postage. Write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St., #21, San Francisco, CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |