Reflections

on

Black

History

______Part 35 |

Los Angeles Bound

by Thomas C. Fleming, May 20, 1998

As an 18-year-old in 1926, when I worked as a bellhop on the Emma Alexander, an intercoastal passenger ship between Seattle and San Diego, I didn't think it was a very hard job, but many of the black crew members quit without warning. There might have been a woman they wanted to stay with in a certain port. And the job paid

very little. With your tips, if you were a hard hustler, you probably could run up your earnings to 75 or 100 dollars a month.

When we returned from the trip north and sailed into San Francisco Bay, the Emma stayed in port for more than 24 hours, and some of us who lived in the Bay Area were given time off. Mama and my sister Kate rented a room in Oakland, and their good landlady had assured me that I could make it my home without sleeping privileges whenever I came in town.

Back at the ship, I joined the other bellhops at the gangplank, snatching the baggage that the porters did not pick up. Then we started ahead of the passengers, who followed us to their cabins. We would curse under our breath if they gave us a quarter or less tip.

The loading went on up until a half hour before sailing time. Then the bell captain would designate one of us to go around, clang a gong and shout, "All ashore that's going ashore!" Friends and relatives who had accompanied the

travelers slowly began drifting off the ship. We had to repeat the call several times.

When the last visitor had gone off, the pilot house gave a signal to the engine room by ringing a bell, and the great marine engines started upper. A tugboat came alongside, the sailors threw ropes to the tug, and then some longshoremen removed the great ropes from the steel capstans on the pier. The huge propellers began to work, and the ship slowly backed into the channel, the hoarse blare of the ship's siren shattering the air. When we were far enough out to clear the pier, the tug turned the ship's prow towards the Golden Gate.

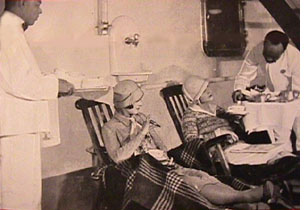

Two members of the Admiral Line's all-black

wait staff serve afternoon tea on deck.

The bellhops would stand by the bell board that was located right off the dining room; it was a switchboard for the whole ship. When people would call in for a bellhop to do something for them, we'd go. And then we would patrol the deck, to serve the passengers who were lounging in big steamer chairs. We tried to provide as many comforts as possible.

The bellhops would stand by the bell board that was located right off the dining room; it was a switchboard for the whole ship. When people would call in for a bellhop to do something for them, we'd go. And then we would patrol the deck, to serve the passengers who were lounging in big steamer chairs. We tried to provide as many comforts as possible.

All the waiters, porters and bellhops were black men. Some porters doubled as waiters while at sea; others took care of the cabins that the passengers occupied, like chambermaids. I don't remember seeing a single black passenger.

Whenever we neared a port, the ship would begin to slow down, and a great deal of bell clanging could be heard from the engine room. A tugboat would come alongside and snuggle the Emma to the pier.

From San Francisco, we sailed south to Wilmington harbor, one of the ports for Los Angles. We discharged and took on passengers and cargo, then set sail for San Diego and Ensenada, Mexico. The ship didn't land in Mexico because there wasn't a good docking facility. Smaller, lighter vessels came out to take passengers ashore, where they bought goods and did sightseeing.

Then the Emma turned north and headed back to Wilmington, and I went into Los Angeles for the first time in my life, taking the commuter trains operated by the Southern Pacific Railway.

The trains fanned out of Los Angeles to a radius of about 60 miles, going into Riverside, Orange and San Bernardino counties. It was a big mistake when these fast electric trains were discarded. People could get about much faster in the metropolitan areas of San Francisco and Los Angeles than they can today.

Los Angeles had a lot more black people than anywhere else in California. They came for the entertainment industry, not because of industrial jobs. I wanted to see Central Avenue, as I had heard so much about the main street of black activity in the city of the angels.

There were several theaters along the street, and many barbershops, hairdressing parlors, restaurants, barbecue places and pool halls -- all the small things that you'd find blacks occupied in, in any city in the United States. Street vendors sold hot dogs, chili and other edibles from pushcarts, on which some sort of fire was kept burning. They sold very cheaply and seemed to do a brisk business.

The Lincoln Theater was the big house on the street, for it not only presented motion pictures, but stage acts of top black entertainers who came through Los Angeles. I took in the Lincoln and enjoyed every minute. There was a very good house band led by Claude Kennedy, and about five or six chorus girls. They went in the entertainment field in hopes of getting in the films too. That's why there was such a big concentration of them down there.

The Lincoln had black audiences primarily; you'd see a scattering of whites. They had the same kind of shows you'd see at the Apollo Theater in New York. There weren't so many of the big-name bands coming from the East, but Los Angeles had some good local black musicians, like Kid Ory, a trombone player who was already a national jazz legend, Curtis Moseby and his Blue Blowers, and Lionel Hampton, who would arrive in 1927, at the very beginning of his career.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Fleming. Email.

At 90, Fleming continues to write each week for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. A 48-page book of his stories and photos from 1907-19 is available for $3, including postage. Send mailing address.

Fleming Biography

More Fleming articles

Back to Front Page

|