Reflections

on

Black

History

______Part 47 |

C. L. Dellums and Mr. Bojangles

by Thomas C. Fleming, Aug 12, 1998

I first met C. L. Dellums in 1927, when I went to work for the Southern Pacific Railroad and joined the Dining Car Cooks and Waiters Union. Dellums was a former Pullman porter, who was active with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. In 1929 he would become its vice president in charge of the West. His union had a sort of checkout office next door to the Cooks and Waiters Union, on 7th Street in Oakland, California.

Dellums made his living from a billiard parlor, located across the street, which had both pool and billiard tables. He had people running it for him. Up above, he had his office. I knew him very well. He was a handsome man, and impeccably dressed. He wore a homburg hat and his shoes were always polished. The way he spoke, you'd think he was a college professor.

I used to talk to him a lot about workers and their problems. He admired me as a young kid who took the positions that I took. I was 19, and you didn't see many youngsters my age joining the union over there.

Dellums was one of the top leaders of the Pullman porters union, all through the long struggle to gain recognition from the Pullman Company, until victory was won in 1937. Later, he was appointed by Governor Pat Brown to the California Fair Employment Practices Committee.

He was the uncle of Ron Dellums, who was elected to Congress in 1970 representing California's 9th congressional district, for Oakland and Berkeley. He served for 27 years as one of the most liberal members of the House and one of the nation's most powerful black politicians.

C. L. Dellums' billiard parlor attracted some luminaries, such as Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, one of the big stars in the Cotton Club in New York. In his day he was the king of all tap dancers, appearing as a headliner on the Orpheum Circuit, which had theaters all over the United States. He worked the year round, appearing wherever there was an Orpheum Theater, making a circuit around the country. The houses of the chain presented a first-run film and stage acts, where the yokels in the land could see all of the most famous entertainers in the world -- comedians, dancers, singers and jazz bands.

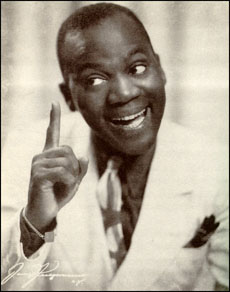

Tap dancer Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, a compulsive gambler and expert pool

player whose off-stage persona contrasted sharply with his media image.

Bojangles was a celebrated pool shark who bet heavily on himself -- as much as $500 a game. Of course, if he lost, he could still continue to play, for in the early 1930s, the Orpheum Circuit was probably paying him $2500 a week. This was before Robinson went into the movies and made films such as "The Little Colonel," "The Littlest Rebel" and "In Old Kentucky" with Shirley Temple and Will Rogers.

Bojangles was a celebrated pool shark who bet heavily on himself -- as much as $500 a game. Of course, if he lost, he could still continue to play, for in the early 1930s, the Orpheum Circuit was probably paying him $2500 a week. This was before Robinson went into the movies and made films such as "The Little Colonel," "The Littlest Rebel" and "In Old Kentucky" with Shirley Temple and Will Rogers.

In Richmond, Virginia, where he came from, he used to tap dance on the street for coins. Then he went to New York. I had read about him in the Chicago Defender, the national black newspaper.

He used to come through the Bay Area every year, and I would go to see him, either at the Orpheum in Oakland or the one in San Francisco. He used to wear tails on stage. Most of the time he was the only black on the bill. They'd have a set of stairs on stage so he could dance up and down. He was the first one to develop that style. And he'd carry on some chatter, because he didn't have any voice for singing. I wasn't a big fan, but I felt a lot of racial pride for a black man to be doing well like that.

Bill was an uneducated man. He loved to hang out in poolrooms when he wasn't dancing, or get in poker or crap games. When he came down to the poolroom, it attracted a lot of onlookers because he was good with the cue -- he was very good. I heard the pool hustlers talk about how he would clean out everybody but this guy Garbie. The others couldn't stay with him because the saying was, Bojangles had long money, and the other guys had short money. Garbie was a pool hustler, and he used to take him every time.

I went down there to see him play once, and after I heard him talk, I didn't bother any more. In person, he was rude and crude. Every other word was m***********, all day long. I just got sick of listening. It looked like he didn't know any other form of speech. That was the big complaint I heard about him locally here.

I could see that he didn't have any class. People who knew him well knew that. But it was strictly the street blacks who played him up, because he was famous.

He was very domineering. The police chief in one city gave him a gold badge and made him an honorary police officer, and gave him a permit to carry a loaded gun all the time. He'd go into one of these places where there was gambling and do all this big talk, and when he got in an argument, he'd flash that gun on people. Everybody respected that gun.

The black middle class just admired him as a dancer, the same way I did.

He wasn't kind of person you could like very easily. When I heard his foul mouth, he dissipated a lot of the admiration I had for him. To me, he was a bully and a coward. I was surprised that he lived as long as he did.

Copyright © 1998 by Thomas Fleming. Email.

At 90, Fleming continues to write each week for the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's African American weekly, which he co-founded in 1944. A 48-page book of his stories and photos from 1907-19 is available for $3, including postage, and a 90-minute cassette tape of his recollections of black life in Florida, Harlem and Chico from 1912-1926 is available for $5, including postage. Send mailing address or call 415-771-6279.

Fleming Biography

More Fleming articles

Back to Front Page

|