|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 76 |

Black attorneys and California politics

by Thomas C. Fleming, May 19, 1999 In the 1930s, Leonard Richardson was the most successful black attorney practicing law in Northern California. More than half of his practice was nonblack; he had a lot of people from Portugal as clients, plus other Latinos. Len was a graduate of the University of California at Berkeley, who was commissioned as an officer in World War I. He was a lieutenant in one of the black outfits that served in France. When he came back after the war, he went to Hastings College of the Law in San Francisco, and after graduation, opened an office on 7th Street in Oakland. During the Depression, Len Richardson was like an elder brother to me. He had a very good home on Derby Street in Berkeley, where Ping-Pong tournaments were held on weekends, and I was a member of the Richardson team. Whist, and bridge when it became popular, were other pastimes. I played a hand when Charles Houston, the dean of Howard Law School and one of Thurgood Marshall's teachers, came to the Richardson home. Houston was also the chief lawyer for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and spent some time traveling about the nation on NAACP business. Another visitor I met over bridge was Ralph Bunche, who was then a graduate student at UCLA. In 1950, for his work as a mediator for the United Nations in the Middle East, Bunche would become the first black person to win the Nobel Peace Prize. Houston, Bunche and other prominent blacks who visited the Bay Area would always come by the home of either Richardson or Walter Gordon Sr., another black attorney, who lived on Acton Street in Berkeley. Walter had also graduated from the UC Berkeley, where in 1918 he was the first All-American football player from the campus. Among other things, Gordon was the first black police officer ever to be hired in Berkeley, a job he held while an undergraduate at the University of California and while attending Boalt Hall School of Law on the UC campus. Walt had a wife and two small children, and worked as a patrolman at night. He served under Chief August Vollmer, who was nationally known as one of the premier criminologists. Vollmer's reputation was so good that he was lured away from Berkeley to go to Chicago. Vollmer served for a couple of years, then resigned with the statement that the only way to clean up the Chicago police was to fire every member and start anew. In the late 1920s and early '30s, Walt had a law office on the second floor of a bank at San Pablo and University avenues in Berkeley. After graduation from Boalt Hall, he also became a coach and chief scout for the Cal football team. He was one of the best-known blacks in the city. He probably made more money from his connections with the university than he did in the practice of the law, until Earl Warren was elected governor of the state in 1942. Gordon and Warren were old friends, who had graduated from the same college and the same law school. Warren started his political career as the crime-busting district attorney of Alameda County -- which includes Berkeley and Oakland. He was a crusader against vice of all sorts, and used to lead raids on suspected gambling dens and houses of prostitution. Warren was a protege of old Joe Knowland, the press lord who owned and operated the Oakland Tribune, who was the Republican Party boss of Alameda County. Warren's name was respected by people who engaged in illegal activities. The word was that he always carried an axe with him, to batter down doors to gain entry. When Warren became governor, he appointed Gordon to the state parole board, which was a first, for no other black had ever held such a high appointment in California state government. In 1945, Senator Hiram Johnson died, so Earl Warren appointed Joe Knowland's son, Billy Knowland, to fill Johnson's seat in the United States Senate. When Warren was appointed by President Eisenhower as Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court in 1953, it was a blessing for the civil rights movement. The following year, the Warren-led court ruled segregation in schools because of color to be illegal. Warren followed with several other decisions that paved the way for Lyndon Johnson's affirmative action decree of 1967.

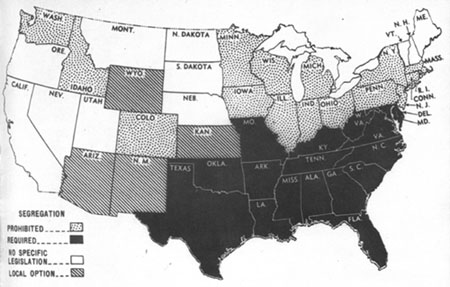

Public school segregation in the U.S., 1954. That year, in Brown vs. Board of Education, the Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren ruled raced-based segregation in public schools to be illegal. The decision became the cornerstone of the civil rights movement in the South. Warren's activities as a strict constitutionalist astonished Eisenhower and perhaps Joseph Knowland, the conservative patriarch of the Oakland Tribune and one of the three most powerful Republicans in the state. Warren offered the name of Walter Gordon to Eisenhower to be appointed as governor of the Virgin Islands. The president took the advice, and the Senate confirmed the nomination.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. This column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Fleming's 100-page book, Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934, is available for $7 plus $2 postage. Send request to tflemingsf@aol.com, or write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St #21, San Francisco CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |