|

Reflections on Black History ______ Part 82 |

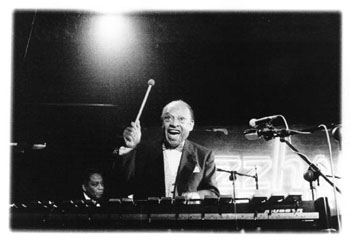

Lionel Hampton, King of the Vibes

by Thomas C. Fleming, Aug 18, 1999 From the 1930s until today, Lionel Hampton has been a major figure in the jazz world. Hamp came out to Los Angeles in 1927, when he was about 18, and soon made his reputation as a great drummer in the Les Hite band, the house band at Frank Sebastian's Culver City Cotton Club, a smaller, West Coast version of the original Cotton Club in Harlem.

Born in 1908, Lionel Hampton became a professional drummer while still in his teens, and also learned the keyboard well. He first played the vibraphone in a recording session with Louis Armstrong in 1930, which produced the hit record "Memories of You." Since then, Hampton has been known as "King of the Vibes," while enjoying an international reputation as a bandleader and composer. Two of his symphonic works, "King David Suite" and "Blues Suite" have been performed often by leading orchestras throughout the world. Los Angeles then had quite a solid black nightclub scene. The L.A. Cotton Club show was broadcast every night over the radio. In the San Francisco Bay Area, we used to stay up late to hear shows there. The Hite band was well known all along the Pacific coast, and Hite and his band would come north in periods when the Cotton Club closed for short periods. He played one-night stands in Oakland and some towns in Oregon and Washington. I met Lionel in L.A. in the 1930s; I don't remember how I met him, but I used to go down there all the time on the train. The Bay Area, with a much smaller black population than other parts of the country, was never an area where there was a lot of jazz music. None of the big jazz bands with national reputations played in San Francisco. Although there were dance halls in the city, they used only local bands, who played "hot" or jazz music just occasionally. I was surprised when Lionel joined Benny Goodman in 1936 and started playing the vibes, because he was better known as a drummer. He still gets on the drums occasionally. Benny was named the King of Swing by the whites media, but the musicians knew better. He was not in the same league with many of the other bands. He could not swing like Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Cab Calloway, Count Basie, Andy Kirk, Earl Hines or Chick Webb. Most people do not know that Benny Goodman, to get the black sound of jazz, hired Fletcher Henderson to arrange full-time for the Goodman band. Fletcher a composer, arranger and bandleader, had the first black big band that became really famous. He might have been the first to start writing arrangements for sections; he had four reeds, sometimes five, and three or four trumpets, three trombones, then the piano, bass, drum and guitar. I guess he wasn't working enough to keep his payroll going, so he started arranging for other bands, and Goodman approached him and asked, would he work for him? You don't know how crazy the white kids got about swing music in the 1930s. It was something new to them. Benny caught on with the white population, playing the way he was playing. The big white turnout made him. If he hadn't got that, he would have gone nowhere. Black musicians couldn't appear in a lot of the places where Benny Goodman could, and Benny got on radio before the blacks did. He used to come on every Saturday, broadcasting nationwide, on a program called Let's Dance. A lot of the white kids never heard of the black musicians. Goodman was the most popular of all the white bands, and he immediately went out and got some blacks to play in his band. He got Teddy Wilson, who was a famous piano player, and he formed a small group out of his big band, called the Benny Goodman Trio, with Wilson on piano, Gene Krupa on drums, and Benny playing clarinet. They made a lot of records together. When he got Lionel Hampton to join them, they really were jumping then. I don't recall any white bandleader who integrated his band before Goodman. I think he did it for commercial reasons. He was trying to get the true feeling of jazz. He was well trained, a thorough musician. Black musicians would say: "That cat's really swinging." That's why blacks called it swing music: they had had a saying out here -- "swinging like a gate." Blacks played differently than whites did, and Goodman copied their style of playing. I could tolerate him, and I used to listen to him every Saturday night when he came on, because I like that type of music. But he wasn't playing as well as the black bands. He didn't understand how to improvise. His clarinet playing reminded me of a guy who was trained in classical music. Almost any black band outswung him. I knew that, and he knew it too. I listened to all the bands, black or white. I don't think I ever had any bias against white musicians. I used to buy a lot of white records when I was in high school. I'm a jazz fan, and I know what sounds best to me. I'm not saying white jazz musicians weren't good, but I thought blacks played jazz better than they did, because it seemed they had a different emotional approach to music. The white guys had those music stands up there, and they'd turn the pages while they were playing. The blacks had those stands too, but they never looked at them. During World War II, Lionel Hampton was drafted into military service as a member of the St. Mary's Preflight Band, stationed at St. Mary's College in Moraga, California in the Bay Area, where they were training Navy flyers. They had about a 20-piece band, who were all professional musicians in civilian life -- and man could they swing! The Navy wanted them as a showpiece band, and they played wherever the Navy wanted them to play. Out of that group was the nucleus of the big band that Lionel Hampton formed when the war was over. During the war, my sister Kate lived in Oakland, and her boyfriend was Wilton Johnson, a very good alto saxophone player from Sacramento who could also write musical arrangements and compose. Wilton was a member of the Preflight Band, who would be in Lionel Hampton's band after the war. Wilton used to come by Kate's house all the time, and sometimes Lionel would come with him, because he liked the way Kate made lemon cream pie. They were both in uniform. I used to talk to Lionel then. He always remembered I was Kate's brother. Lionel was very versatile. He played the piano two-fingered style, just like he did on the vibes. Two fingers! He'd drop the mallets on the vibes, jump up on the piano and start playing. He didn't have what I'd call one of the great bands, but they were exciting to watch -- a great show band. I've seen them play over here. They would come off the stage even, and go down the aisle of the theater, all tooting behind him, and then back up to the stage. Lionel married a woman named Gladys, who was a showgirl in Los Angeles, in a chorus line. Gladys was about eight or nine years older than Lionel, and it caused a lot of comment among us who knew him. They never had any kids. Lionel made Gladys handle all the money. That's what made him well off. When they used to play one-night stands for dances, all over the country, Gladys would stand in the box office and watch the money as it came in, and help them to count it, to make sure the band got theirs. And she put that money away very carefully. She invested the money in real estate deals in Harlem, because she had the business sense. He didn't. He was just a musician. I think Lionel is still performing. But he ought to cut that out. He moves around stiffly now, and he wears that rug on top of his head; I noticed because it's always slipping down. I want to get close enough to ask him, "Man, why don't you take that goddam rug off your head?" I know him well enough that I could go up there and talk to him like that.

Copyright © 1999 by Thomas Fleming and Max Millard. Produced exclusively for the Columbus Free Press, this column is edited by Max Millard, who has conducted over 100 hours of interviews with Fleming, and blends Fleming's spoken words with his writings. Born in 1907, Fleming is the founding editor of the Sun-Reporter, San Francisco's oldest weekly black newspaper. Fleming's 100-page book, Black Life in the Sacramento Valley 1850-1934, is available for $7 plus $2 postage. Send request to tflemingsf@aol.com, or write to Max Millard, 1312 Jackson St #21, San Francisco CA 94109.

Fleming Biography More Fleming articles Back to Front Page |