A lawsuit over toll booths in Honduras shows how corporate trade policies make life unlivable in poor countries — and send people fleeing north.

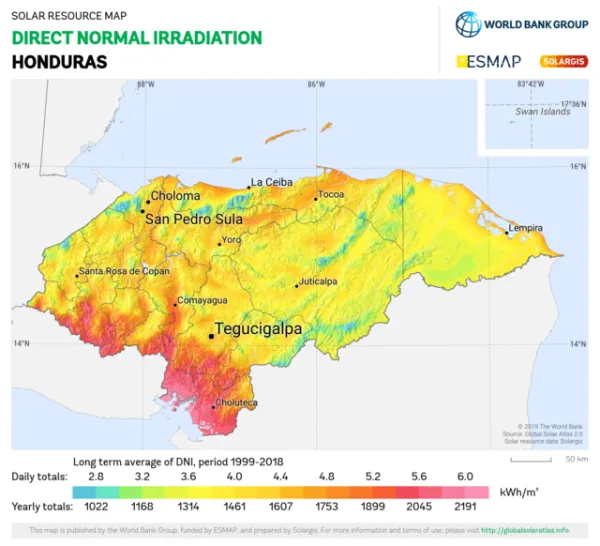

Honduras DNI Solar-resource-map GlobalSolarAtlas World-Bank-Esmap-Solargis.png; © The World Bank, Source: Global Solar Atlas 2.0, Solar resource data: Solargis

Many of us know the pain of paying steep tolls, especially when a turnpike is taken over by a private company.

Now imagine you live in one of our hemisphere’s most impoverished countries. Do that and you’ll get a glimpse into how unfair trade deals help make life unlivable in many countries — and force countless people to seek a living in countries like the United States.

When a private company suddenly put up toll booths in the middle of a taxpayer-funded highway, local residents in El Progreso, Honduras were furious.

They knew the new fees would also hike the price of food, bus fares, and their daily commutes — and that making it in their country, where roughly half of the population lives below the poverty line, was going to become unbearable.

So local businesses and residents joined forces to stop the company from charging fees. For 421 days, starting in 2016, the Angry Citizens Movement stood night and day — even on weekends and holidays — at the “Camp for Dignity” along the highway. With handwritten signs and chants, they urged their neighbors not to pay. Even after facing tear gas, police repression, and threats, the movement persisted and expanded.

Eventually, they won — but not without consequences.

At the end of 2017, with the 24-hour camp still in place, the U.S.-backed President Juan Orlando Hernández managed to get reelected, even though presidential reelection is illegal in Honduras and there was widespread evidence of fraud. Mass protests lasted for weeks and the toll booths were burned. The company’s contract was finally canceled in 2018 amid accusations of corruption.

Now, the private toll booth operator — backed by big U.S. banks, including JP Morgan Chase Bank and two Goldman Sachs funds — is suing Honduras through a process called international arbitration. They’re claiming $180 million, more than four times what the company reportedly invested.

It doesn’t matter that the project lacked public support, that the government institution that negotiated the contract was shut down under a cloud of corruption, or that now former President Hernández, who struck the highway deal, was convicted in the U.S. for drug trafficking earlier this year. What matters is the profit.

Lawsuits like these are only possible because of exclusive privileges for foreign investors found in many international trade agreements, investment laws, and contracts like this one. Under this “Investor State Dispute Settlement” system, foreign investors can sue governments for losses and future claimed profits over decisions they believe affect them.

Currently, Honduras faces at least $14 billion in claims from foreign and domestic corporations. That’s equivalent to roughly 40 percent of the country’s GDP in 2023 and nearly four times its public investment budget for 2024.

In our new study into this avalanche of claims, we found that the majority of investors are revolting against Honduran efforts to reverse or renegotiate corrupt deals struck under Hernández, which were often damaging to the public interest and local communities.

And if these investors succeed, the economic burden on the country will only deepen the displacement crisis driving Hondurans to migrate north.

The blatant injustice of these corporate claims is increasingly recognized at the international level. The former UN Special Rapporteur for human rights and environment, David Boyd, has called them “a catastrophe for development.” Notably, the U.S. recently removed these corporate privileges in its trade relations with Canada.

Now it’s time for the U.S. to end these privileges in its other trade agreements including with Central America — and not sign any more that include them. That would be a good first step toward respecting the efforts of Hondurans and all people to live and prosper in their own countries.