Every February, we rediscover inventors. We share portraits, post quotes, and remind one another of names that were overlooked. For a moment, history expands. Then March arrives.

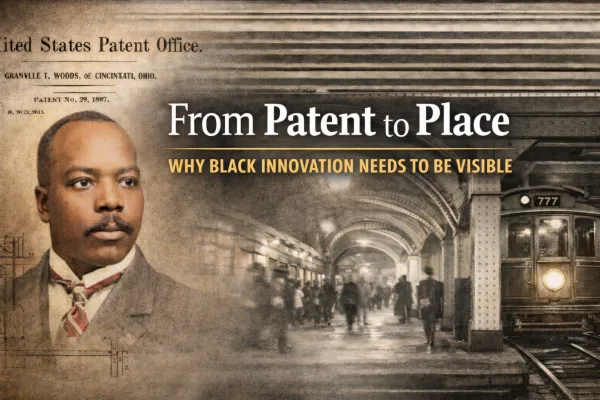

Granville T. Woods held more than fifty patents related to electrical systems and rail communication. His work improved how trains operated and communicated, helping shape the transportation systems that connected American cities. His innovations mattered — yet most people have never heard his name.

Not because his work was small, but because patents do not build monuments. A patent proves invention. A textbook preserves information. But neither guarantees visibility. If a story does not take up space, it can quietly fade from public view.

That is the difference between recognition and presence. We can say someone mattered and still fail to make their story visible. When history occupies real space — a building, an exhibit, or a restored artifact — people encounter it differently. It becomes part of the landscape. It becomes harder to overlook.

Scale changes memory.

Some innovators are remembered through institutions, museums, and architecture. Their names are attached to buildings. Their stories are embedded in public space. Others remain confined to documents.

Granville T. Woods helped shape systems that millions still rely on today. But his story rarely occupies physical space in our cities. That is not simply an oversight. It is a reminder that public memory is built — not automatic.

Moving from patent to place is intentional work. It means taking innovation that lives on paper and giving it visible form. It means restoring artifacts, creating exhibits, preserving structures, and ensuring that important stories remain present long after a commemorative month ends.

This is not about replacing one story with another. It is about balance. If innovation helped build our infrastructure, its remembrance should be just as solid.

Black History Month invites rediscovery. That matters. But rediscovery is only the beginning. The deeper work is permanence — making sure that when people walk through a neighborhood, visit a historic site, or step into a restored piece of infrastructure, they encounter the full story of American innovation.

Recognition starts the conversation. Place ensures it continues. And that is the work in front of us.

WATCH THE DOCUMENTARY

____________

Michael D. Aaron is the President and Executive Director of the Rickenbacker Woods Foundation.