The Legal Battle Over A Treatment Plant Built By French Multinational Veolia Points To A Hidden Source Of Oil Industry Harm.

In rural West Virginia, largely hidden among steep hills, stands a $255 million facility designed to transform fracking waste into freshwater and food grade quality salts. Proponents hailed it as one of the most important environmental projects undertaken by the oil and gas industry in recent U.S. history. But local conservation groups and residents remained skeptical from the start, warning that the plant could leak toxic waste into water and air, harming human health and ecosystems in a largely forested region where tight-knit communities live close to the land.

The facility, called Clearwater, was built by the Denver, Colorado-based oil and gas extraction company, Antero Resources, and an affiliate of Veolia, the multinational French waste, water and energy management company. It lies in the heart of north central Appalachia’s booming Marcellus and Utica gas fields — America’s top natural gas-producing region — and was built to process 600 truckloads per day of fracking wastewater. Laden with heavy metals, chemicals and other contaminants, this waste frequently exhibits levels of radioactivity hundreds of times the safe limits set by regulators.

The developers’ hopes were initially high. At a meeting in September 2015 at the courthouse in Doddridge County, West Virginia, Conrad Baston, the general manager of civil engineering with Antero, suggested salt produced during the waste treatment process could be called, “Taste of the Marcellus,” after the gas-rich geologic formation from which it came. “It’s the best project like this in the world,” Kevin Ellis, Antero’s vice president of government relations, told a West Virginia newspaper in 2019. “Bar none. Period.” Ellis is currently Antero’s regional vice president in Appalachia, and Baston is still stationed with Antero in West Virginia.

Antero was to own the treatment plant and supply it with fracking waste from its nearby oil and gas extraction operations. Veolia would design, build, operate and maintain the facility under a 10-year agreement in return for more than $255 million, Antero said in 2015.

Clearwater began operating in November 2017, according to one drilling industry news site. But a mere 22 months later, the facility was idled, and Antero and Veolia are now locked in a half billion-dollar legal battle over the plant.

On March 13, 2020, Antero filed a lawsuit against Veolia in the District Court of Denver County, Colorado. The complaint, obtained by DeSmog via a public records request, accused the company of fraud, breach of contract, gross negligence, and willful misconduct, and demanded at least $457 million in damages.

“Clearwater was a failure,” reads the complaint. “Veolia promised[] a ‘turnkey’ facility” where Antero would “simply ‘turn the key’ and have everything function as intended” but “Veolia failed at every turn,” the complaint alleges. The filing further alleges that Veolia “started cutting corners even before the project started,” “hid” vital design flaws, and made modifications that were “ill-conceived, untested, and poorly implemented” and ultimately “doomed the commercial viability of the facility.” According to the complaint, the idling of the plant in September 2019 had nothing to do with a drop in natural gas prices, the reason Antero officials stated to a Pittsburgh newspaper at the time. The real explanation, the complaint alleges: “The facility simply did not work.”

Meanwhile, in extensive comments to DeSmog, Veolia has defended Clearwater. “Veolia has and continues to strongly disagree with Antero’s allegations,” said Carrie Griffiths, executive vice president and chief communications officer for Veolia North America. “In particular, Veolia emphatically denies that it committed fraud.”

On the same day that Antero filed its lawsuit, Veolia filed counterclaims for more than $118 million. On January 3, 2023, the Denver County district court found that Antero had prevailed on its claims for breach of contract and fraud, awarding the Colorado energy company approximately $242 million in damages, plus interest, and reasonable costs and attorneys’ fees. “We respectfully disagree with the court’s decision and will file an appeal against it,” Griffiths told DeSmog in late March. In April, the District Court reduced the amount of damages. As of late August, Veolia’s appeal in the Colorado Court of Appeals was still pending.

Antero did not respond to repeated requests for comment.

The oil and gas industry has long faced criticism for the role the carbon emissions from burning its products play in causing climate change. But the legal battle over Clearwater opens a window into a problem that has received far less scrutiny: A regulatory vacuum governing the industry’s radioactive waste. Multinational companies have seized lucrative opportunities to clean up this mess. But a lack of transparency has made it almost impossible for communities to hold such companies to account when projects fail, or understand the kinds of health or environmental risks they may pose.

“If they were coming from Europe and had a superior system that would actually free us from the pollution and the toxicity that would be welcome,” said Jill Hunkler, executive director of Ohio Valley Allies, a grassroots advocacy group fighting for environmental justice in northern Appalachia.

“But it doesn’t seem like that is what happened,” Hunkler said. “And because they are from another country, it is going to be much harder to hold them accountable.”

Business Opportunity

Long before Veolia broke ground on the Clearwater plant, building a facility to treat fracking wastewater looked like a promising commercial opportunity.

Known as “oilfield brine” or “produced water,” the wastewater created by the drilling industry has long proved a headache for oil and gas companies.

For the past several decades, most of this waste has simply been pumped back underground — an approach fraught with problems. Disposing of the wastewater in this way often requires lengthy road trips in gas-guzzling trucks to reach injection wells — also referred to as saltwater disposal wells — where the waste is injected deep into the earth. These controversial facilities often encounter local opposition. The U.S. Geological Survey has linked injection wells to earthquakes, and in Ohio, within the last two years, state regulators have determined that on four different occasions injection wells have leaked fracking wastewater into natural gas wells. A recent case attributed to nearby injection wells in Kingfisher County, Oklahoma, involved copious amounts of saltwater bubbling up out of the earth and into wheat fields.

“Produced water is by far the largest wastestream created by the upstream oil and gas industry and over 90 percent of it is injected in disposal wells,” said J. Blake Scott, a 30-year industry veteran, who used to run an oilfield service company. He is now president of Waste Analytics, a Texas-based oilfield waste data firm. Given the problems with injection wells, and transporting the wastewater to them, Scott said, the industry has pursued a variety of projects to treat and clean the waste, providing “the potential to make large sums of money for waste disposal companies.”

In a 2019 report, Florida-based financial services firm Raymond James & Associates recommended that potential investors should do their homework on the oilfield wastewater sector.

“Most investors are simply unaware of the fact that as crude production grows, produced ‘dirty’ water grows even faster,” the report said. “This growing dirty water problem should create opportunities for investors.”

But a combination of loose regulations and a lack of official data on oilfield brine has left industry free to shape the narrative for investors and the public on fracking waste treatment, painting this complex and dangerous wastestream as relatively harmless, DeSmog has found.

Both government and academic researchers have established that, despite the innocent-sounding name, brine contains toxic levels of salt, heavy metals such as lead and arsenic, and the radioactive element radium. “Analyses of the water produced with the gas commonly show elevated levels of salinity and radium,” a 2011 U.S. Geological Survey report noted. The best spots to look for gas, said a report on the Marcellus published in 2008 by the Pennsylvania Geological Survey, is not necessarily where the shale is thickest, but where levels returned by the Geiger counter are highest. “To put it simply,” the report states. “RADIOACTIVITY = ORGANIC RICHNESS = GAS.”

Pennsylvania regulators have found radium in brine of the Marcellus formation at levels thousands of times above the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) safe drinking water limits, and hundreds of times above the level at which the EPA formally defines a wastestream as “radioactive waste.” Information provided by the EPA indicates the sludge that forms on the bottom of tanks and trucks that hold brine can contain even higher concentrations of radium, and also striking amounts of radioactive lead and polonium.

Fracking has added to this onslaught of toxic waste. Chemicals used in the fracking process return to the surface in the weeks and months after a well comes online, as a highly dangerous wastestream called “flowback.”

The EPA does not keep track of amounts of brine and flowback that issue from wells. But according to a 2021 report of the Oklahoma-based Groundwater Protection Council, the United States produces some three billion gallons of brine and flowback every day from both conventional wells and unconventional (fracked) wells. If a year’s worth of this oilfield wastewater were put into a standard oil barrel, and the barrels were then stacked atop one another, they would reach the moon and back nearly 22 times.

“Clean Products”

The Clearwater facility planned for Doddridge County, West Virginia, may have represented the oil industry’s biggest attempt to date to tackle this problem. The facility, according to Antero’s August 2015 press release, would take in approximately 60,000 barrels of Antero’s brine and flowback each day, or about 600 truckloads, saving the company millions of dollars on transport to injection wells, and enabling it to reuse treated water from the plant in fracking operations rather than pipe in freshwater. But neither Antero nor Veolia disclosed details on exactly how the plant would safely treat such a copious volume of this challenging wastestream.

Clearwater was going to transform 98 percent of the incoming wastewater, according to a set of frequently asked questions, and replies, about the facility that was posted on Antero’s website but is no longer up, “into clean products: salt and freshwater.” The treated water would be used to frack new Antero wells in the region, meaning drillers would no longer need to rely on West Virginia’s water resources for the water-intensive operation. As for the salt, state permits acquired by Antero indicated that the plant would generate approximately 4.25 million pounds (1,900 tonnes) of salt per day. Antero engineer Conrad Baston said a portion of the salt is “food grade quality” and could be used either for road salts, to melt snow and ice, or for other commercial purposes. Nevertheless, a description of the project on Antero’s website stated, “Antero has proposed an onsite landfill to safely and efficiently dispose of salts.” At the 2015 meeting at the Doddridge County Courthouse, Baston told the community, to some disbelief, that the landfill liner would last “thousands of years.”

Although Antero might not have the name recognition of a major U.S. oil and gas company such as ExxonMobil or Chevron, it has established solid credentials and pitched itself as a mature investment. Its headquarters, on Wynkoop Street in downtown Denver, Colorado, is in a hip and bustling part of the city. One of its directors attended Harvard Business School, and Yale University took a stake in Antero in 2015, with investments peaking at $230 million the following year, according to a 2018 article in the Yale Daily News. By the end of 2018, the university’s investment had dropped to $357,000, Yale Daily News reported. Yale did not respond to a DeSmog request for comment.

“High Standards”

Antero’s disposal of oilfield waste has run into opposition in the past. In 2011, a Colorado newspaper reported on a controversy in Eagle County involving disposal of Antero’s pit liners, which are used to contain oilfield waste at the drill site and can be coated in contaminants.

Still, West Virginia state officials were enthusiastic about Clearwater. “Antero’s planned advanced wastewater treatment complex in Doddridge County is good for the environment and good for West Virginia’s economy,” West Virginia Governor Earl Ray Tomblin (D) said in 2015.

In the August 2015 Antero press release, Veolia said the company was “pleased to partner with Antero” on the project. Veolia touted the project’s “high standards for social responsibility” and said it would use “unique technologies” to “provide a reliable and sustainable solution for flowback and produced water treatment.”

Veolia, in a 2017 press release, said the project would be supported by the expertise of its “Nuclear Solutions entity” and “Veolia will also provide a comprehensive Environmental Health and Safety program to protect Veolia’s employees and subcontractors, the public, and the environment.”

“Once operational,” stated a project description on Antero’s website that is no longer up, “Antero’s facility will directly support 21 permanent employees as well as 25 supply chain service jobs.”

Pollution Concerns

From the outset, many local residents were wary.

Clearwater was built on a hill in Doddridge County, not far from the border of Ritchie County. In this part of West Virginia, many people live on land that has been in their family for generations, in homes they built themselves. They grow or forage some of their own food and medicine, including ginseng and morel mushrooms, and fish and hunt for trout and deer. While former U.S. president Donald Trump carried 69 percent of the vote in West Virginia in the 2020 presidential election, the state also has a fervent independent streak, with a progressive Mountain Party occasionally fielding promising candidates, and many residents are leery of corporate America after decades of contamination by the coal industry.

Clearwater’s placement in this landscape concerned locals.

Toward the end of 2015, a batch of letters arrived at theWest Virginia Department of Environmental Protection (WV DEP), the state’s main environmental protection agency, asking it to deny the facility its air quality permit. “Here in Doddridge County we’ve seen permit after permit approved. Permits that allow pollution of the air we breath [sic] with hazardous carcinogenic poisons,” resident Eric Bernhardt wrote. “This proposed facility would add significantly to the burden of air pollution which we have to process through our lungs.” A letter from another Doddridge County resident, Linda Ireland, stated: “Our county is already besieged by the gas industry—well pads, diesel truck traffic, compressor stations, pipelines, and major processing facilities…already emit toxic substances into our air. We who chose the fresh air, clean water, and quiet of country life find these destroyed.”

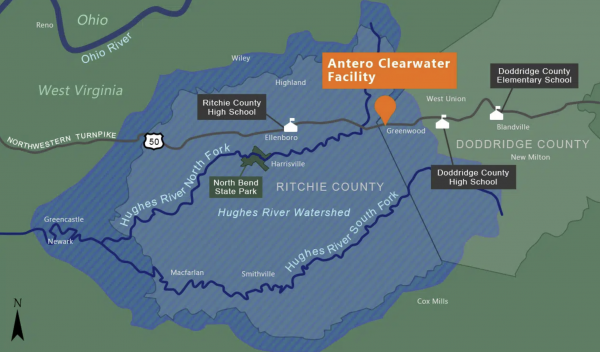

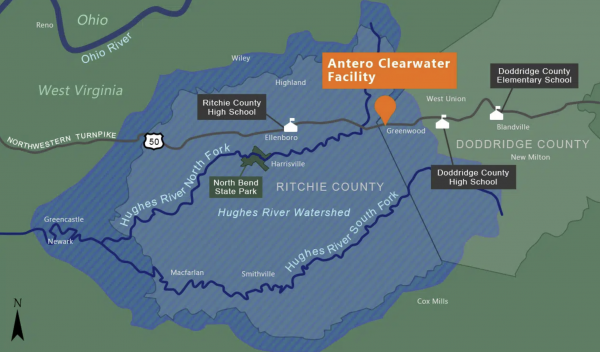

A map of the landscape around the Clearwater facility. Map credit: Sabrina Bedford.

It wasn’t just Doddridge County residents who were worried. Vickie Nutter, a Ritchie County resident and member of a conservation group called Friends of the Hughes River Watershed, told DeSmog, “The North Fork Hughes River is Ritchie County’s only public water source, and the wastewater treatment plant and landfill is adjacent to it.”

“For our region, this may be the worst of the worst,” the Doddridge County Watershed Association posted on Facebook in July 2016. “This will NOT bode well for our watersheds.”

In the September 2015 meeting in the Doddridge County Courthouse, available on YouTube, residents remained suspicious of the facility and pressed Antero executives on just how the plant would deal with the radioactivity in oilfield wastewater. One man asked if Antero could provide “an absolute assurance” there would be no radium in the salt produced. A woman questioned whether Antero would be willing to work with researchers to monitor radioactivity.

“If your industry is putting out even the least, the least little bit of radiation, radon, whatever you think is going to…damage future generations—beware!” exclaimed another woman. “And don’t lie, don’t shove it under the rug…We don’t want another Chernobyl.”

Bill Hughes, an industrial electrician who had become a self-taught sleuth on oilfield radioactivity, also raised his concerns. (Hughes passed away in 2019.)

“At no point did you address the highly radioactive Marcellus shale,” he said. “Heavy metals, and the radioactivity, need to be addressed up front, clearly, squarely, and honestly, because this plant, if it works, it would be great. If it’s done poorly, if it’s not perfectly designed, installed the way it’s designed, operated in accordance with standard operating procedures, with a lot of failsafe features, we risk a massive amount of potential water contamination,” and “we all have friends or relatives in Ritchie County and downstream of here.”

“Has this ever been done with Marcellus shale quality produced water,” Hughes asked. “Ever, anywhere?”

Baston did not directly answer this question, and instead recited annual radioactivity doses the American public received.

“We are working with some of the best radiation experts in the industry,” he said. “We have evaluated our materials, and the public exposure risk from our plants or where this material goes is essentially non-detect.”

A Global Business

Veolia Environnement SA, branded as Veolia, has a long and storied history. The French firm began as Compagnie Générale des Eaux, or CGE, founded in 1853 by an imperial decree from Napoleon III.

Veolia now works in 48 countries, acting to replace services traditionally managed by public authorities, such as providing drinking water and managing waste. For instance, in London, Veolia provides recycling, waste management and landscaping; cleans streets, and maintains parks and open spaces. In Morocco, the company distributes drinking water and electricity. In India, the company treats and provides drinking water and manages wastewater. In southeast Asia, Veolia has worked on water treatment solutions for the cosmetics industry, and has recently developed new desalination technology.

But there have been complaints about the company’s practices, too.

A May 2023 report on the Veolia-operated Yerbabuena Landfill in Colombia by the international advocacy group Global Witness stated it has received municipal trash, and also domestic waste from a nearby oil refinery. The report highlighted a history of disturbing contamination in the community adjacent to the landfill, noting that a Colombian pediatrician had reported cases of babies being born without a brain, and other newborns emerging scarred with rashes and boils.

During the term of reporting this article, Veolia did not answer specific questions about the landfill, though after the story was published an official with Veolia Latin America contacted DeSmog to say that the Yerbabuena landfill was now called the San Silvestre Environmental Technology Park and that Veolia “strongly denies any allegation of Veolia Colombia disregarding the environmental law within the frame of its operations in the San Silvestre Environmental Technology Park.” Veolia also adamantly denies there has been contamination or health effects in the local population. Griffiths, the Veolia North America spokeswoman, did not reply to questions on how many other projects Veolia is involved with in the United States and around the world related to the treatment or disposal of oilfield waste. “We won’t be able to answer the remainder of your questions,” she told DeSmog in mid-July.

A Veolia webpage advertising produced water treatment services to the oil and gas industry acknowledges the potential difficulties involved. “Safely treating produced water, so that it can be safely discharged into the surrounding ecosystem, does not come without challenges,” the page states. “Tightening environmental regulations, coupled with the need to maintain low capital and operating costs, means operators need an experienced produced water treatment partner they can trust.” The page lists one operational project in Bahrain, an oil-rich country in the Middle East.

In the United States and Canada, the company, often under the name Veolia Water North America, has controversially assumed utility contracts typically handled by government entities in large cities such as Pittsburgh and Seattle, and also smaller ones, including Moncton, in New Brunswick.

Though a significant investment for West Virginia, the $255 million Clearwater project represented only a fraction of Veolia’s global business, which at the beginning of 2016 had a market capitalization of just over $13 billion. The company’s value has since swelled to about $23 billion.

Clearwater was such a peripheral part of Veolia’s multinational operations that the company devoted only a single sentence to the project in its quarterly financial report published in September 2017: “In the industrial market, Veolia will use its expertise to assist Antero Resources in the loading, packaging and proper disposal of sludge generated by its West Virginia industrial site (10-year contract representing cumulative revenue of USD 70 million).”

While the company has sometimes left community anger in its wake, Veolia has pitched itself as a compassionate corporation on the frontlines of combating climate change and helping to create a cleaner world. In late April, Veolia North America sponsored a dinner at the annual conference of the Society of Environmental Journalists in Boise, Idaho.

“The Clearwater project thus fits perfectly with Veolia’s long-term commitment to help its customers succeed in their ecological transformation,” Griffiths said.

“Environmental Nightmare”

Veolia’s initial relationship with Antero appears to have been an amicable one. Antero’s chief administrative officer, Alvyn Schopp, explained in a Clearwater promotional video that was posted while the plant was in operation but has since been taken down that his company was impressed with Veolia’s ability to problem-solve.

“Frankly,” he said, “to spend 200-and-some-odd million dollars on a solution, you have to be sure that that solution is going to work.”

Clearwater, according to the drilling industry news site, began operating in November 2017. The Charleston Gazette-Mail reported that problems began in April 2018, when Antero noticed elevated chloride levels in a stormwater pond, and found liquid had been escaping through the landfill. About a month later, Antero found another section of the landfill liner — presumably the one that company engineer Baston had said would last “thousands of years” — had been torn, the paper reported.

According to a WV DEP inspection report, cited in the Charleston Gazette-Mail article, Antero didn’t call the designated spill line; didn’t tell the agency’s Division of Water and Waste Management; didn’t provide a written notice within five days with a description of the incident and a plan to fix it; and didn’t call the Hughes River Water Board — all actions it was required to take.

“Everything’s going undocumented,” Jim Shreves, president of the local advocacy group, Friends of Hughes, told the Charleston Gazette-Mail, calling the landfill an “environmental nightmare.” The WV DEP issued a notice of violation to Antero, but did not levy a fine.

“It Looks Bad”

A lack of regulation compounded local people’s difficulty in establishing exactly what was happening at Clearwater.

Despite the numerous known hazards in oil and gas waste, the industry enjoys a stunning exemption. In the 1980 Bentsen and Bevill Amendments to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (RCRA), oil and gas waste was classified as non-hazardous — meaning that it receives much less regulatory scrutiny. For example, both the oilfield brine and flowback being processed at the Clearwater plant would be considered non-hazardous.

“No other developed country has such poor regulations and oversight for these upstream wastes as the United States,” said J. Blake Scott, with Waste Analytics.

While the companies wrangled over the operations of the plant, for many residents the facility’s operations remained a mystery. “I don’t know enough to know if it’s bad, but it looks bad,” Dawn Bush told DeSmog in 2019. At the time her family lived in the tiny Doddridge County community of Greenwood, located just 2,000 feet from Clearwater.

“I am a Libra, I see both sides of everything,” said Bush. “And I will tell you, it is really scary to live right there, but I know so many people that work for the gas companies or drive those brine trucks and that is how they take care of their families.” In 2020, Bush’s family left their home in Greenwood, happy to move out from beneath the shadow of Clearwater.

Fracking Waste “About 1,000 feet” From the School Ball Fields

Though by far the largest, Clearwater was not the only ill-fated fracking wastewater treatment project by a European company that angered residents in the Marcellus-Utica region.

Luxembourg-based Apateq is a wastewater treatment company founded in 2013. One of the company’s goals, according to a 2016 press release, is to manufacture and deliver “innovative and cost-efficient…solutions for the treatment of water and wastewater to customers around the world.”

In 2019, in Belmont, Ohio, at a site near the Union Local Elementary School, Apateq and a local company called TROO Clean Environmental set up an operation to treat fracking waste under a gigantic, arching, open-ended white structure resembling an airplane hanger. “The school ball diamond is about 1,000 ft from the boundary of the facility,” an official with the Ohio Department of Natural Resources confirmed in a January 2019 email to an Ohio environmental organizer, who shared the correspondence with DeSmog. “Currently there are no setbacks in rule,” stated the official, “therefore the Division cannot prohibit the facility in this location.”

In Ohio, state laws also enable fracking waste treatment facilities to be developed and built without any public participation. “There is no public notice,” said Hunkler, of Ohio Valley Allies, who lives in Belmont County. “This facility is not just right beside the community, it is in the middle of the community.”

TROO Clean Environmental is no longer in business and its Belmont fracking waste treatment facility is no longer operating. “APATEQ is no longer involved with the Belmont County project,” Brian Ward, Apateq’s head of North America Business Development, told DeSmog in February 2023. When asked specifically why Apateq left the project, he stated, “I cannot speak to details that I am not privy to; plus, NDAs [non-disclosure agreements] remain in effect.”

Radioactivity Concerns

While many people living nearby fracking waste treatment facilities have little idea of the potential hazards, the concerns over radioactivity raised by some locals are valid, according to industry reports, academic and government research, and DeSmog reporting.

Last year, DeSmog published a series of articles about a fracking waste processing facility in Ohio that contaminated an adjacent public road and also the boots of one of its workers with radium. Radiological analysis of sludge samples taken from these boots revealed radium levels roughly 15 times EPA limits for soil at Superfund sites, which are America’s most notorious toxic industrial waste sites.

In other instances, Duke University researchers analyzed sediment at the point where a Pennsylvania oilfield waste treatment facility discharged to a stream and discovered radium at approximately 200 times background levels. And geochemists and environmental engineers at Penn State University and Union College, in New York, have found signatures of oilfield waste accumulating in mussels downstream of Pennsylvania oilfield waste treatment facilities.

It is a problem the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection is aware of, at least in part. The agency published a report in 2016 on potential radioactivity hazards in the state’s Marcellus gas field; it found that facilities treating fracking wastewater were discharging radioactivity into the local environment, and workers at these facilities faced exposure risks.

Meanwhile, in 2020, researchers with Harvard’s School of Public Health published a study in Nature Communications which determined that unconventional oil and gas activities — a reference to the techniques of modern fracking — “could significantly elevate” the amount of airborne radioactivity in downwind communities. The paper listed the handling of fracking wastewater as one of many components of unconventional oil and gas production that could add to the atmosphere’s load of radioactivity at levels that “could induce adverse health effects to residents in proximity.”

Concerns over the public health impacts of radiation in the atmosphere date back decades. “Airborne radioactive emissions from many different man made and natural sources endanger public health” and “poses an increased risk of cancer and genetic damage in humans,” reads a 1979 statement by then EPA Administrator Douglas Costle, part of a press release related to EPA studies on airborne radioactivity. At the time, the EPA actually listed radionuclides — referring to the various isotopes or forms of different radioactive elements — “as hazardous air pollutants subject to possible future regulation by this agency.”

The prospect of regulation caught the attention of the American Petroleum Institute (API), the United States’s most powerful oil and gas lobby, which produced its own 1982 report analyzing the possible impact of regulation of radionuclides as an air pollutant. The report concluded that such regulation “could impose a severe burden on API member companies.”

The API report also recognized the particular dangers of radium in oilfield brine, and provided a warning that seems well suited to an oilfield waste processing facility such as Clearwater. “Any control methodology proposed for radioactive materials must recognize the fact that radioactivity can not be modified or made inert by chemical means,” the API report states. And attempts to remove radioactivity may end up transforming, “a very dilute source of radioactive materials into a very concentrated source of radioactivity.”

“Off the Charts”

A 2018 Clearwater air permit application indicates that elements from the incoming oilfield waste stream, such as calcium, sodium, magnesium, lithium, barium, and strontium would be emitted into the air from the plant’s 39-foot-tall cooling towers, a release called drift loss. The report did not mention radium.

Clearwater’s permit stated that drift loss would constitute just .001 percent of the 2,070,000 gallons of fluid circulating through the plant every hour. In April 2019, when Clearwater was operational, DeSmog visited the boundary of the site with an off duty oilfield waste truck driver and observed a steady flow of brine trucks into the site and tremendous amounts of whitish-gray steam billowing from the cooling towers and into the atmosphere.

“The radioactive levels at the Marcellus shale formation are off the charts,” said Marvin Resnikoff, Ph.D., a nuclear physicist and radioactive waste specialist who has served as a legal expert on cases involving oilfield radioactivity worker exposure. Resnikoff stated if excessive amounts of steam are being witnessed at a plant that processes fracking wastewater then these “treatment facilities are essentially boiling off or distilling water and concentrating the radioactivity” and “the steam should contain radioactive elements.” These emissions, said Resnikoff, “could potentially mix with the hydrologic cycle and” fall out as “radioactive rain.”

Bill Burgos, an environmental engineer at Penn State University who has published several academic articles on Marcellus fracking waste, said the complex chemical makeup of oilfield brine and flowback, including the extraordinarily high salt levels, make it very difficult to treat, and very difficult to remove the radium. The waste can be filtered with certain types of membranes, but to do this successfully can be expensive, and still may leave operators with a waste product “rich in radium.”

Griffiths, with Veolia North America, when asked earlier this year how radium was removed from the incoming waste, said Clearwater’s treatment process had three parts: a pretreatment system that treated solids and dissolved metals; a thermal system where salts were crystallized and separated from the water; and a post-treatment system where the remaining organic compounds were treated by a biological process. “The pretreatment process precipitated radium-containing constituents through a physico-chemical settling process. The radium-containing constituents exited the stream through the pretreatment system’s sludge waste,” Griffiths said.

When presented with information from the air permit application, and questioned on whether or not it would be appropriate to assume that radium would have been released in the steam, Griffiths replied: “Air testing was under Antero’s responsibility.” When asked if the steam was ever tested for radioactive elements commonly found in oilfield wastewater, such as radium, Griffiths replied: “As previously stated, air testing was under Antero’s responsibility.”

Antero has not replied to questions on how the plant worked and how it may have removed radium from the plant’s emissions, or whether they were ever checked for radioactivity.

When DeSmog asked WV DEP in 2019, whether the plant had a permit to release radioactivity into the air, and whether or not the agency was testing the steam the plant was releasing for radioactivity, spokesperson Casey Korbini said that the agency issues permits in accordance with federal and state air quality statutes, “and radionuclides are not a regulated pollutant under these statutes.”

He added: “This does not mean that radionuclides are prohibited; they are simply not regulated.”

On January 15, 2020, officials with WV DEP and the West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources performed an unannounced site visit to Clearwater. “On the walk through of the processes used at the facility, the Radiological Health staff used a Ludlum Model 2241-3 meter to take readings at various locations,” stated a report filed that February to Antero by Tera Patton, the health department’s radiologic health chief.

The report revealed that the health officials observed radioactivity levels commonly in the range of 50 times background levels, and as high as 160 times background levels. Several U.S. government environmental and health agencies, and also the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers, consider a work area to be contaminated if radioactivity levels are more than twice background radiation levels. Still, after the January 2020 unannounced visit, West Virginia officials stated: “No violations were written to the facility at this time.”

“Radiation Exposure”

If the scope of possible radioactive air pollution was impossible to establish, so was the whereabouts and possible radioactivity of vast quantities of solid waste.

Clearwater may have produced as much as 144 million liters of waste sludge, and 2.8 billion pounds of waste salt, during its 22 months of operation, according to DeSmog calculations based on plant specifications in project permits. Where did all these waste byproducts go, and were they ever transformed into commercial salts?

“The sludge was transported to several disposal sites in the United States,” Veolia’s Griffiths said. “Given the confidentiality provisions contained in the agreements signed by Veolia and the current dispute with Antero and the ongoing proceedings, Veolia is currently not in a position to provide more information.”

Griffiths added, “To Veolia’s knowledge, all the salt was disposed of in the landfill adjacent to the Clearwater facility” and “to Veolia’s knowledge, Antero never produced commercially marketable salt.” Antero has not replied to questions on the whereabouts of the sludge or salt produced at the plant, or whether the salt was ever commercially marketed. The WV DEP has not responded to repeated questions on the whereabouts of these byproducts.

Julie Weatherington-Rice, Ph.D., an Ohio earth scientist who has focused on oilfield waste for more than 40 years, said landfills that contain excessive amounts of oilfield waste sludge are destined to become Superfund sites and will be radioactive for tens of thousands of years, given that the half-life of radium-226 is 1,600 years. In a paper published in 2013 in the scientific journal New Solutions, researchers from the University of North Texas School of Public Health, in Fort Worth, and the University of Texas at Arlington, looked at waste sludge from fracking operations. They found elevated levels of radioactivity and warned that the practice of siting oilfield waste pits in residential communities “will increase the potential for radiation exposure to the general public.”

“Making it Vanish”

Eight years after Antero’s presentation on the Clearwater project in the Doddridge County courthouse in West Virginia, and four years after the plant was idled, many of the residents who raised radioactivity concerns are no longer engaged, or have passed away.

Fracking continues in rural West Virginia, the industry continues to produce an inordinate amount of waste, and a portion of America’s gas is now headed to Europe as liquefied natural gas. “The oil and gas industry has succeeded in taking this enormous aspect of their operations and making it vanish,” said Carroll Muffett, president of the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), a nonprofit legal organization based in Washington, D.C., and Geneva, Switzerland. “Is this recognized in the European public? Almost certainly not, because it is not even recognized in the places where it is happening.”

Clearwater is offline, and the seemingly endless fleet of fracking waste trucks continue to traverse the region’s roads from wellhead to injection well and back again. Dawn Bush still lives in the area and drives by the Clearwater plant regularly. “To me, it is a shame,” she told DeSmog in August, “because they took that whole hillside out, restructured all that land, put that monstrosity up and it is such an eyesore, and gosh — it was for nothing.”

Meanwhile, 111 million people around the world draw water from their tap thanks to Veolia. And each week Londoners place distinctly colored trash bags to the curb for the company’s fleet of garbage and recycling trucks to collect. A March 2021 Veolia press release announced that within the city of London the company would be operating “a full fleet of Electric Refuse Collection Vehicles.” Veolia may be a name many of these people know, but Clearwater is likely a name they do not. The same year that the facility began processing fracking waste in rural West Virginia, Veolia opened its new global headquarters in the Paris suburb of Aubervilliers. The building is known as the “V”, contains multiple interior gardens, and is certified by various sustainable architecture alliances.

In July 2022, Veolia named a new chief executive officer, Estelle Brachlianoff, a former senior executive vice president of Veolia’s UK & Ireland operations. In a video statement, Brachlianoff speaks glowingly of the “circular economy,” and the wonder she experienced in first joining Veolia decades ago.

“To be the global leader of ecological transformation is a huge responsibility,” she said. “You can count on me to stand alongside you as we meet the major challenges of our age together.”

This article was originally published on September 19, 2023, and was updated on September 22, 2023 with comment from Veolia Latin America.