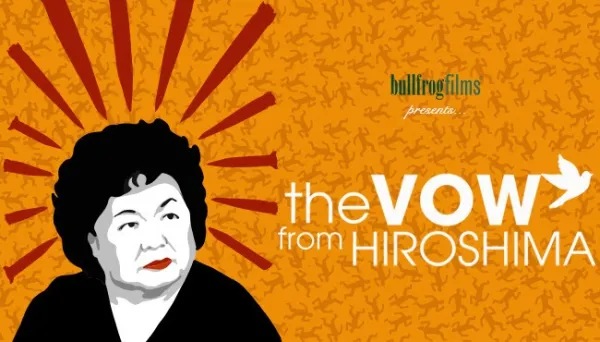

The new film, The Vow From Hiroshima, tells the story of Setsuko Thurlow who was a school girl in Hiroshima when the United States dropped the first nuclear bomb. She was pulled out of a building in which 27 of her classmates burned to death. She witnessed the gruesome injuries and agonizing suffering and indecent mass burial of many loved ones, acquaintances, and strangers.

Setsuko was from a well-off family and says she had to work at overcoming her prejudices against the poor, yet she overcame an amazing number of things. Her school was a Christian school, and she credits as influence on her life the advice of a teacher to engage in activism as the way to be Christian. That a predominantly Christian nation had just destroyed her predominantly non-Christian city didn’t matter. That Westerners had done it didn’t matter either. She fell in love with a Canadian man who lived and worked in Japan.

She also left him temporarily in Japan to attend the University of Lynchburg very close to where I live in Virginia — something I didn’t know about her until I watched the film. The horror and trauma she’d been through didn’t matter. That she was in a strange land didn’t matter. When the United States tested more nuclear weapons on Pacific islands from which it had evicted the residents, Setsuko spoke against it in the Lynchburg media. The hate mail she received didn’t matter. When her beloved joined her and they couldn’t marry in Virginia because of the racist laws against “intermarriage” that came out of the same racist thinking that had created the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that didn’t matter. They got married in Washington, D.C.

That victims of Western wars had and almost entirely still have no voice in Western media and society didn’t matter. That anniversaries recognized on Western calendars were and almost entirely still are pro-war, pro-imperial, pro-colonial, or otherwise celebratory of pro-government propaganda didn’t matter. Setsuko and others in the same struggle decided to create at least one exception to these rules. Thanks to their work, the anniversaries of the nuclear bombings on August 6th and 9th are memorialized around the world, and antiwar monuments and memorials and parks marking that pair of tragedies exist in a public space still dominated by pro-war temples and statuary.

Setsuko not only found a public voice speaking about the victims of war, but helped build an activist campaign to abolish nuclear weapons that has created a treaty ratified by 39 countries and rising — a campaign focused on educating people about the past victims and potential future victims of war. I recommend joining that campaign, telling the U.S. government to join the treaty, and telling the U.S. government to move money out of nuclear weapons and other components of the war machine. The campaign Setsuko worked with also won a Nobel Peace Prize, marking a departure for the Nobel Committee which had been trending away from giving that prize to anyone working to end war (despite the stipulation in Alfred Nobel’s will that it need do just that).

What if we were to take Setsuko’s work and accomplishments not as a freak occurrence to be marveled at, but as an example to be replicated? Of course, the nuclear bombings were unique (and they’d better stay that way or we’re all going to perish), but there is nothing unique about bombings, or burning buildings, or suffering, or destroyed hospitals, or murdered doctors, or ghastly injuries, or lasting contamination and disease, or even the use of nuclear weapons if we consider depleted uranium weapons. The stories from the firebombed cities of Japan that were not nuked are as heartbreaking as those from Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The stories in recent years from Yemen, Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, Syria, Libya, Somalia, Congo, Philippines, Mexico, and on and on, are just as moving.

What if U.S. culture — engaged in major transformations at present, ripping down monuments and possibly putting up a few new ones — were to make space for victims of war? If people can learn to listen to the wisdom of a victim of Hiroshima, why are victims of Baghdad and Kabul and Sanaa not speaking at big public events (or Zoom calls) to large groups and institutions across the United States? If 200,000 dead merits attention, shouldn’t the 2,000,000 or so from recent wars? If nuclear survivors can begin to be heard these many years later, can we speed up the process of hearing from the survivors of the wars that currently motivate nuclear possession by various governments?

As long as the United States goes on engaging in horrific, one-sided, mass-slaughters of distant people about whom the U.S. public is told little, targeted nations like North Korea and China will not give up nuclear weapons. And as long as they do not — barring a transformational enlightenment within or vastly enlarged courageous opposition without — the United States will not either. Ridding humanity of nuclear weapons is the obvious, most-important, end in itself and first step toward ridding ourselves of war, but it’s unlikely to happen unless we move forward on ridding ourselves of the whole institution of war at the same time.