Advertisement

A new documentary film, Far Out: Life On & After the Commune, directed by Charles Light, tells the story of a group of leftwing journalists who splintered off from what was known as Liberation News Service (LNS). With candid then-and-now footage, Light’s eighty-five-minute film reveals the communards as young hippies and senior citizens, and shows how their paths intertwined with folk/rock superstars to fight the good fight.

One of the film’s co-stars is author and historian Harvey Wasserman who is also the longest active contributor to The Progressive. His first article for the magazine, about campus protests, “Reform, Not Revolution”, appeared in August 1967, while his most recent, “Drones, Nukes, and the Myth of Reactor Safety,” was published in January. The irrepressible veteran activist was interviewed via telephone in Los Angeles for the following conversation, which has been edited for length and clarity.

Q: What was the Liberation News Service?

Harvey Wasserman: LNS was a pioneering news service that provided articles to the underground press, which consisted of about 400 counterculture newspapers burgeoning throughout the country in 1967 and 1968. We were antiwar, pro-civil rights and pro-pot legalization and known as the “Associated Press of the underground.” LNS was launched the day before the October 21, 1967, March on the Pentagon.

Q: How did your commune grow out of LNS?

Wasserman: It’s living proof of the law of unintended consequences. The FBI infiltrated our news service. As part of COINTELPRO, J. Edgar Hoover sent agents into LNS to break it up. We’d moved to New York City, and agents instigated horrible anti-gay attacks at our meetings against co-founder Marshall Bloom. George Harrison gave Marshall permission to screen the Beatles’ Magical Mystery Tour movie at Fillmore East benefits, and with that money, Marshall bought a farm in Massachusetts, where we secretly relocated with our mimeograph machine in August 1968: Montague Farm in Massachusetts.

Q: What was it like transitioning to living off of the land?

Wasserman: We didn’t know what we were doing. We were all suburban kids. We froze the first winter. Gradually, we learned how to live in the country, in a farmhouse. The first major decision came in the spring, when we were planting our garden and some wanted to spray. But one woman, Cathy Rogers, sort of the farm’s matriarch, said, “No, we’re not using chemicals.” We actually revived for our whole generation the whole ethos of organic farming. Within a couple of years, the garden was magnificent. To learn how to do it, we used a handbook on organic gardening.

Q: How were women involved in life at the communal farms?

Wasserman: They ran the place. The antiwar and civil rights movements in the early days were run by men. Women, in many cases, weren’t treated particularly well. A lot of the feminist movement came out of the communes. The environmental movement has really been a women’s movement, in touch with Mother Earth.

Q: Some of the communards were gay. How did other commune members react to that?

Wasserman: You have to ask them. If you had asked me back then what it meant to be gay, I had no idea. A lot of it was new to us.

Q: What were relations like with other local residents in the area?

Wasserman: All over the map. We were like aliens landing in Montague. Mostly the locals didn’t know what to make of us. We were smart enough to form relations. The farmer down the road had a maple sugar operation. He needed labor when he’d gather the maple syrup from the trees; we drove the tractors and emptied the buckets. In many cases, we formed really beautiful relations with locals.

Q: The communards went back to the land to remove themselves from a New Left factional fight. But how did the outside world catch up with you?

Wasserman: Some of us had a mindset to escape politics; others stayed active. The Vietnam War was still on. We considered our presence in the countryside to be very political. Then, as fate would have it, the world came to us. In December 1973, we opened the local paper and on the front page was an aerial photo of the Montague Plains and superimposed on it was an artist’s rendition of a nuclear power plant they wanted to build there.

Collectively, instinctually, we said, “No fucking way we’re going to let them build this in our backyard.” We deepened our opposition to nuclear power by studying the books Secret Fallout by radiologist Ernest Sternglass, and Poisoned Power by Manhattan Project scientist John Gofman.

Q: The film Far Out contends that the commune’s opposition to the construction of this plant sparked the U.S. grassroots anti-nuclear movement.

Wasserman: The first thing is we came up with the slogan “No Nukes,” printed the first bumper sticker and T-shirt; it’s gone global ever since. Northeast Utilities put up a tower at the proposed site to test wind direction and in February 1974 Sam Lovejoy took a crowbar and knocked over the tower. Dan Keller and Charles Light, from the commune, who made Far Out, earlier also made the documentary Lovejoy’s Nuclear War.

In Seabrook, New Hampshire, you had really great antiwar activists. We’d drive up from Montague to Seabrook for meetings about a proposed nuclear power plant. The town was really against it—Seabrook voted four times to not allow the plant to be built. It became an issue of home rule.

We hooked up with the American Friends Service Committee in Boston. They taught us the Quaker tradition of nonviolent resistance. On August 1, 1976, 100 people went onto the construction site; eighteen were arrested. Keller and Light made a movie about this, too, called The Last Resort.

On August 22, we had a bigger demonstration; 180 people were arrested. We thought we could stop Seabrook by occupying the site. On April 30, 1977, we had a few thousand people at the rally; 1,414 were arrested at the site. The rightwing governor demanded that we post bail, so about 1,000 hippies were jailed in five National Guard Armories around the state, which became world news. At the end of two weeks, 550 people still refused to give bail.

Q: What role did musicians play in these protests?

Wasserman: In the summer of 1978, we were allowed [by local authorities] onto the Seabrook site, then under construction, and we held a peaceful, illegal rally with Pete Seeger, Jackson Browne, and 20,000 people.

Jackson, Bonnie Raitt, James Taylor, Carly Simon, and Graham Nash started doing concerts [to raise awareness, and funds, for the anti-nuclear efforts]. They were already involved in the movement. They said, “We gotta do a big concert, let’s go to Madison Square Garden.” Bruce Springsteen signed on and we added concerts. The four nights sold out immediately, and we decided to add a Sunday concert and rally at Battery Park City, in Lower Manhattan. We ended up with between 200,000 and 250,000 people. It was the Woodstock of the seventies. Then demonstrations started happening all over the country.

Q: How did the success of these concerts impact the communes?

Wasserman: New York was a complete psychedelic miasma [laughs]. We’d been in the country for ten years of communal living and all of a sudden, we were in Manhattan, at Madison Square Garden, and encountered all this money, media, and fame. It really took us to another place and kinda shattered the farm. But the commune did hold together. A core community stayed at the farm through the 1980s and 1990s, and in 2003 we sold it to a Buddhist community. People from the farm who stayed in Massachusetts are still active and just defeated a bad battery facility they wanted to build nearby. We’re all still anti-nuclear.

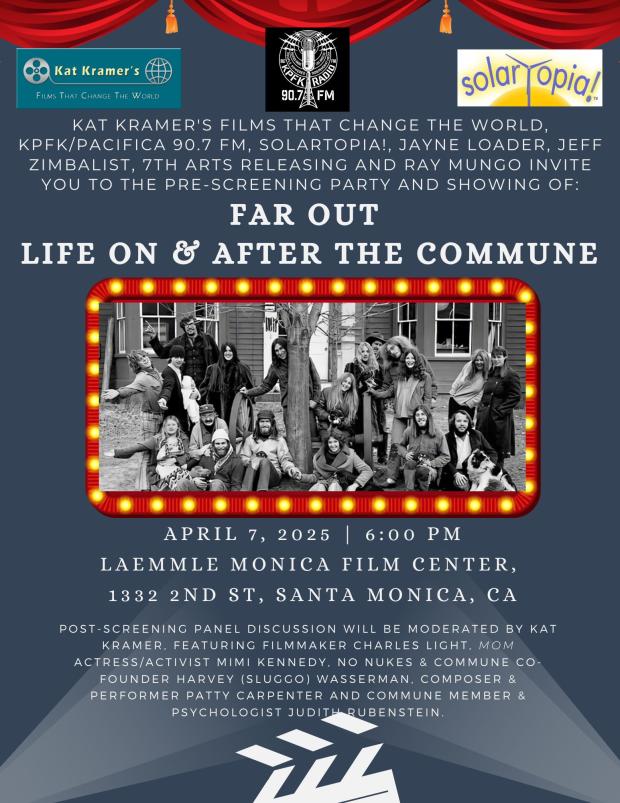

Far Out: Life On & After the Commune will be showing at five Laemmle venues in California (Encino, Glendale, Santa Monica, Claremont and Newhall) at 10:00 a.m. on April 5 and 6 and at 7:00 p.m. on April 7 as part of Laemmle Theatres’ Culture Vulture series.

There will be panel discussions with filmmaker Charlie Light, Harvey Wasserman, and musician Patty Carpenter. The panels take place after the 10:00 a.m., April 5 show at Encino; the 10:00 a.m., April 6 show at Glendale; and the 7:00 p.m. screening at Santa Monica. The panel on April 7 also includes Mom actress/activist Mimi Kennedy and Judith Rubenstein, commune member and psychologist.

Published in cooperation with: