When, three weeks ago, Rolling Stone published a horrific story about University of Virginia's rampant and systemic rape culture enabled by its own administration's complicity, we may have expected that their editors had braced themselves for the backlash that would inevitably ensue. After all, as anybody familiar with rape advocacy – or, even more likely, is or is close to a survivor of sexual assault – knows, whenever a rape is denounced, forces beyond the victim's imagination surge to bombard her and her advocates with all sorts of accusations, doubts and demonization attempts. The survivor's life is scrutinized; their past, their lifestyle, their sexual history, all are reviewed and questioned, in search of character failings that might undermine her story. That story, her account of the violence she underwent, most of all, is probed and prodded endlessly; any discrepancy, however random, is immediately raised against her as 'proof' that the whole thing never happened. That it was all a manifestation of her over-active imagination, hatred towards men, or maybe even a good old bout of hysteria. That the idea that she could have undergone such extreme violence and that there existed someone to inflict it was preposterous in the first place. Meanwhile, the point of view of the perpetrator is considered, sought-out and often believed. It is often subject to much less questioning than the victim's story, as the idea that it did not, could not have happened seems like the more 'rational' possibility, the one which makes us less uncomfortable. That scenario is so common it could be called a cliché if we cared about style not substance. If we have been lucky enough to be spared from it ourselves, we've witness it in high-profile cases, like the Strauss-Kahn debacle or the Polanski case or wee know about it from our sisters, nieces and friends, who had to go through it. When a survivor makes the decision to speak up about their sexual assault experience, she is usually aware of what is coming; that is why that decision is often so difficult. Yet the moment Rolling Stone was confronted with this expected development, it collapsed and printed a retraction.

There are many things wrong with this retraction, not least of all its unambiguous blaming of the victim. While Rolling Stone's article tackles multiple instances of rape at UVA, the narrative revolves predominantly around Jackie, a student who was gang-raped in a prestigious fraternity at the beginning of her freshman year. The perpetrators were never prosecuted criminally, nor were they reprimanded in any way by the UVA administration, and Sabrina Rubin Erdely, the Rolling Stone investigator who authored the story had to actively seek out Jackie's testimony for the article. But Rolling Stone no longer stands by their 'primary witness', claiming that “In the face of new information, there now appear to be discrepancies in Jackie's account, and we have come to the conclusion that our trust in her was misplaced.” It is injurious enough that Rolling Stone's editors would suddenly turn on the victim, whom they not only used and instrumentalized to make their story more sensationalistic – the fraternity gang rape is described in more detail and vulgarity than necessary (''Most of all, Jackie remembers the pain and the pounding that went on and on”)– but also pretended to defend and support against the indifference of UVA's administration. Following the hyper-mediatized publication of a story which proclaimed to unveil systematic personal and institutional violence through the lens of the injustice made to Jackie, Rolling Stone undoubtedly had a 'duty of care' to the heroine which they held up, claimed to support, and forced to carry their banner. It is now known that Jackie asked to no longer be mentioned in the article, a request which Rolling Stone denied her, which not only constitutes a blunder in journalistic ethics but makes the magazine's subsequent turn on Jackie even more abhorrent.

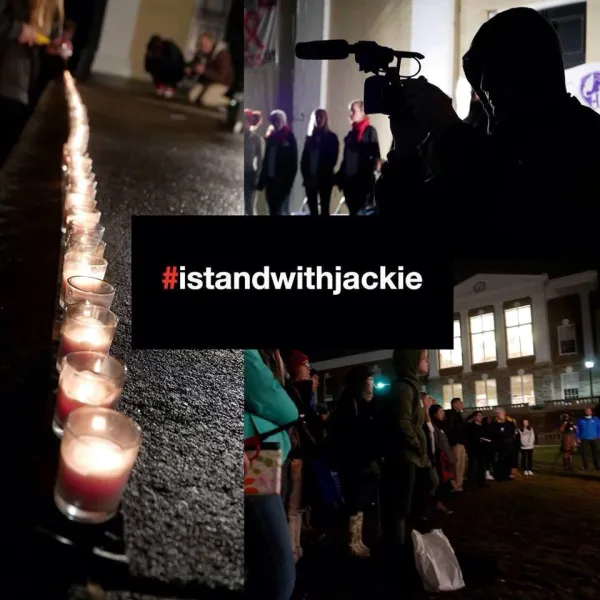

Most mainstream news outlets, following the Washington Post's lead, have reacted to the retraction by casting doubts on Jackie's story. But it wasn't the official statement of the fraternity under scrutiny in Erdely's article, Phi Kappa Psi– which, unsurprisingly, contested elements of Jackie's story – that shifted the story in public discourse, it was undeniably the Rolling Stone retraction. As it was repeatedly pointed out on the twitter channel #IStandWithJackie, frat boys closing ranks and denying that they conduct sexual-assault-based hazing rituals is not highly surprising. Furthermore, that a prestigious, wealthy fraternity at a prestigious, wealthy university would receive legal advice so as to draft a statement making them appear respectable and reasonable and pointing out inconsistencies in the victim's story is also not particularly shocking. What appears more remarkable, instead, is Rolling Stone's precipitous bow to the arguments of those whom they so vehemently denounced in their article.

When Rolling Stone's Managing editor, Will Dana, tweets that he “can’t explain the discrepancies between Jackie’s account and the counter statements made by Phi Psi” one cannot help but wonder whether he has even read his own magazine's investigation into UVA's deeply ingrained rape-culture. Does he remember Erdely's description of a “deeply loyal campus,” in which Greek life was prevalent, even domineering, where administrators were obsessed with prestige and reputation, and in which going public with rape accusation were seen as 'tantamount to betrayal'? In this context, was it so difficult to envision, even to predict, that the story of the woman who dared not only to speak out but to speak out to a major national magazine, sparking national outrage and scrutiny toward's UVA's sacrosanct 'traditions' and even the temporary suspension of Greek life, linchpin of their culture, would be met with vehement resistance, from at least some strata of the student body? If the administration took the appropriate steps to rein in the public relation backlash and protect themselves from potential lawsuits, it cannot be expected that a culture would radically change so abruptly; thus Jackie's fellow students' doubts about the validity of her story are not unsurprising, neither is Phi Kappa Psi's defense, and Will Dana should certainly not have been taken by surprise.

Standing out from the chorus of Jackie abjurations, a few articles bravely shift the blame from Jackie herself to the Rolling Stone Editors, particularly their responsibility in omitting to fact-check parts of the victims' story, and failing to contact the alleged perpetrators. It is their failure, not Jackie's, which will hinder progress and undermine strides recently made in rape-survivor advocacy and against rape-culture. Yet these arguments do not go far enough. While Jackie's story has been under attack, the core of it remains intact: even assuming that all her detractors' claims are true, it would still not necessarily mean that she has not been sexually assaulted at UVA. The precise circumstances of her assault are still to be determined – and the place for that is certainly not the mainstream media – but until then, her account of her experience should be respected. There are many reasons why the discrepancies in question may have arisen: trauma might have led her to misremember some details, she might have chosen to change some facts for self-protection, she could have been lied to by her assailant, or records could have been meddled with to make her appear to be lying. And there is the small but real possibility that her story is altogether false. But that possibility is none of our concern for now: the burden of proof, in cases of rape, should lie with the accused, not the victim. And until the accused has successfully fulfilled that burden – with hard evidence, not through claims that Rolling Stone, once more, did not think appropriate to fact-check – then I will resolutely and adamantly keep standing with Jackie.

---------

The Free Press welcomes Jeanne Kay to our team Europe coverage. Follow her at @jeannekay27