BANGKOK, Thailand -- One year after destroying a popular elected

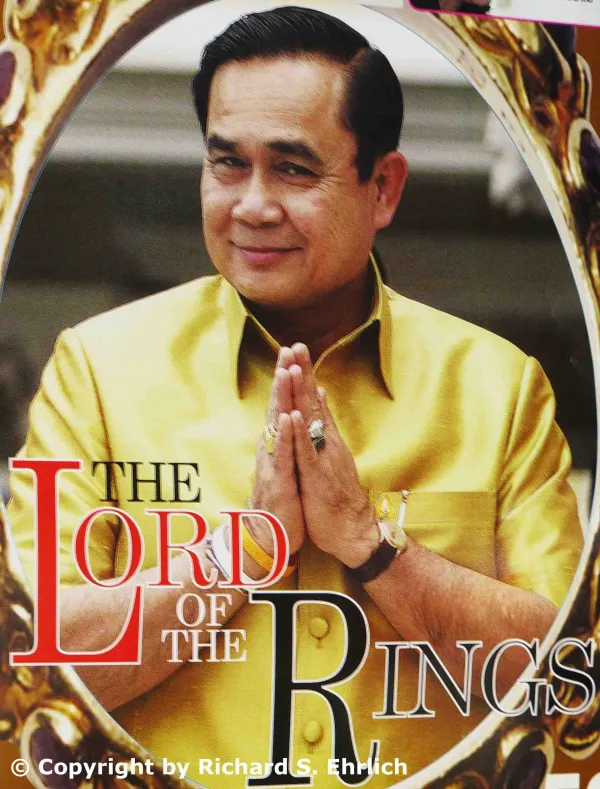

government in a bloodless coup, Gen. Prayuth Chan-ocha rules with

absolute power over a country suffering from newly discovered "death

camps" for Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants, a flat economy, and

diplomatic feuds with the U.S. and Europe.

Gen. Prayuth publicly shrugs off Washington's criticism of his May 22,

2014 coup and his junta's military trials and coercive "attitude

adjustment" confinement for civilian dissidents.

After ripping up Thailand's constitution, he orchestrated an interim

charter giving himself absolute power as prime minister "regardless of

the legislative, executive or judicial" branches, plus immunity from

prosecution.

Gen. Prayuth then empowered Thailand's U.S.-trained army to officially

function as police by seizing property and detaining suspects.

"Even though we didn't like the coup, we train Thailand's military so

that in the future when all this settles down, America will still have

good relations with Thailand," said one American who trains Thailand's

paramilitary rangers and special forces.

"We are playing the long game, because of our competition with China

in this region.

"General Prayuth's problem is he is not a politician. And he has a lot

of loose canons under him. He is a good officer, respected by his

troops, but he is now in over his head," the American military trainer

said on May 17.

Gen. Prayuth often appears uncomfortable and testy when journalists

question his policies.

But he exudes confidence. When asked about the possibility of a

counter-coup against him, Gen. Prayuth responded last week:

"Who would topple me? What half-wit would do anything like that?"

In April, he described his irritability by saying, "When I see red, I

sometimes end up with a splitting headache. Who knows, the veins in my

brain might burst and I could die before the woes of this country get

dealt with."

On May 19, the coup-toppled former prime minister Yingluck Shinawatra

posted $900,000 bail and pled not guilty to "dereliction of duty"

charges resulting from her rice crop subsidies which cost billions of

dollars during her 2011-2014 administration.

Ms. Yingluck faces other charges including questionable financial

compensation to Red Shirts and other supporters who were injured or

killed during pro-democracy protests in 2010.

Gen. Prayuth participated in a 2006 coup which ousted her influential

wealthy brother, former prime minister Thaksin Shinawatra, who is now

a international fugitive dodging a two-year prison sentence for

corruption.

The general's royalist and right-wing supporters are meanwhile

entrenching themselves to prevent any return to power by Ms. Yingluck,

Mr. Thaksin or their allies.

Gen. Prayuth and his supporters are expected to eventually unveil a

constitution restricting future elections to a minority of

parliamentary seats under a system dominated by pro-junta appointees.

Though they have been repeatedly out-voted during national polls, Gen.

Prayuth's mostly Bangkok-based supporters praise his coup for ending

months of street clashes which killed more than 20 people before his

putsch.

They hail the general as a stern, sincere leader dedicated to

establishing stability, in contrast to Thailand's squabbling,

unpredictable and often deadly democracy.

"I have no doubt Gen. Prayuth had good intentions when he seized

administration of the country by force," Bangkok Post contributing

editor Atiya Achakulwisut wrote on May 5.

"I believe him when he says, repeatedly via interviews and his weekly

Friday briefing, that he stepped in to stem the increasing violence

and to save lives from being lost," she said.

Gen. Prayuth's critics say the political violence before his coup was

incited by his supporters so he could step in as Thailand's savior.

Today, Gen. Prayuth is under international scrutiny for his handling

of Muslim ethnic Rohingyas and Bangladeshis who want to land on

Thailand's tourist-friendly beaches during their desperate, often

fatal attempts to cross the Indian Ocean in overcrowded, ill-prepared

boats.

Thousands of Muslim men, women and children are escaping racism and

stateless status in Buddhist-dominated Myanmar, and harsh poverty in

Muslim-majority Bangladesh.

They are trying to reach prosperous Muslim-majority Malaysia and

Indonesia by transiting Thailand's land and waters.

Illegal human traffickers in all five countries exploit them for cash

or as slaves, frequently holding them hostage during voyages while

demanding thousands of dollars extra to continue their passage -- or

else.

In recent weeks, Thai authorities discovered their gruesome so-called

"death camps" in southern Thailand near the Malaysian border.

Hundreds of Rohingya and Bangladeshi migrants had been secretly

imprisoned in dozens of jungle-based smugglers' camps, alongside at

least 37 graves of those who died from disease or malnutrition or were

allegedly murdered because they were unable to pay ransoms.

Gen. Prayuth responded by not welcoming the boat people to land.

He then invited Southeast Asian officials along with U.S. and other

Western representatives to Bangkok on May 29 to discuss the worsening

tragedy at a "Special Meeting on Irregular Migration in the Indian

Ocean."

Bangkok "will not push back migrants stranded in Thai territorial

water," the foreign ministry announced on May 20.

Gen. Prayuth meanwhile also faces a southern insurgency by minority

ethnic Malay-Thai Islamists.

On May 14, they unleashed a scattered three-day assault in Yala

province with improvised explosives, wounding 22 people and damaging

36 businesses and institutions.

The insurgents' fight against "Thailand's colonizers" is to

reestablish an annexed 100-year-old Muslim homeland in the southern

provinces of Yala, Pattani and Narathiwat where more than 6,000 people

have been killed on all sides since 2004.

China has offered a diplomatic and financial lifeline to Gen. Prayuth

by warmly embracing his junta, refraining from public criticism of his

coup, and arranging military and economic deals.

China is offering to extend its existing southern transport routes --

on the Mekong River and by highway across Laos -- into Thailand where

Beijing wants to build a lucrative fast railway line to speed Chinese

exports to Bangkok's port on the Gulf of Siam.