BANGKOK, Thailand -- When the CIA, Thai police, Chinese guerrillas and

others were linked to Southeast Asia's wealthy heroin dealers during

the 20th century, no one imagined fruit and vegetables would provide

delicious replacement crops to fight the official corruption and

rescue impoverished tribes growing opium in northern Thailand.

"Our project is the only one in the world that has succeeded in

replacing opium with other crops. No other country has done it,"

Prince Bhisadej Rajani, director of the Royal Project opium crop

replacement program said in an interview.

The project claims to enable more than 100,000 indigenous Hmong,

Yao, Akha, Karen and other ethnic tribal people to grow fruit,

vegetables, herbs, flowers, mushrooms, tea and coffee instead of

opium.

Initiated in 1969 by King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the project was

helped by U.S. taxpayers but is now supported by Thai government

subsidies, packaging and marketing.

The farms on land formerly used for opium fields also attract

officials from Laos, Myanmar and Colombia who hope to replace their

countries' drug crops or, in Bhutan, curb rural poverty.

But when Prince Bhisadej and a handful of experts flew to Kabul,

Afghanistan, about 10 years ago to see if that war-ravaged nation

could copy Thailand's anti-opium experiment, their U.S.-supported trip

ended in failure.

U.S. security forces escorted them to a village which did not grow

opium, but was next to another village which grew illegal poppies.

"We introduced some new crops for those particular non-opium

people, so the opium people would try and copy," Prince Bhisadej said.

"But nobody wanted to do the organization" to transport the

replacement food crops to markets and arrange for them to be sold.

"The Americans have their aircraft bringing food to the American

soldiers, about three or four flights per day. The [crop replacement]

produce could be sent back by the American planes, which go back

empty" to Kabul and other cities where markets are available, he said.

But his suggestions were ignored and the program was shelved.

As a result, "the village I went to, where I was taken to, now are

opium growers."

Some of Thailand's so-called "hill tribes" continue to grow a

relatively tiny amount of illicit opium, which is cooked and

concentrated into stronger heroin powder for domestic consumption and

international export.

But most of this country's narcotics zone has been pacified by the

agricultural Royal Project.

In 1970, Thailand was producing more than 200 tons of illegal opium

each year, "enough to supply the annual needs of every heroin addict

in the United States two or three times over," according to a Royal

Project report.

After studying robust peach stems grafted onto weaker peach trees,

King Bhumibol decided to end opium growing by introducing peaches and

other crops which could thrive in the north's cool weather and not

compete with hotter lowland farms.

Tribes were given seeds and saplings, plus transportation and other support.

The new crops were sold at local markets, much cheaper than fruit

and vegetables imported from America and elsewhere.

Prince Bhisadej said he met American Agricultural Research Service

(ARS) officials in the early 1970s soon after the project began, who

offered cash "to find crops to replace opium."

ARS is the U.S. Agriculture Department's research wing and was

interested "because the opium got into America. It was being smuggled

in," after being converted into heroin, he said.

Eventually, Washington paid more than $6 million to fund 80

projects in the north, said the prince who is now 96 years old.

U.S., European and U.N. financing rapidly advanced the program

before sloping off, and the Thai government's annual multi-million

dollar subsidies now keep the Royal Project afloat.

"We don't make a profit. We sell the vegetables and the fruit. Our

transportation expenses, and so on, are deducted from our income. The

rest we give to the hill tribes," the prince said.

"About 98 percent" of Thailand's previous opium production was

stopped thanks to crop replacements and police suppression, he said.

At a high-profile public relations dinner in Bangkok on March 4,

Prince Bhisadej gave a speech describing how the Royal Project was

hosting 50 foreign chefs from some of the world's finest restaurants

and had taken them the project's farms.

The chefs met the tribes, witnessed their rustic cooking

techniques, tasted their traditional meals and then returned to

Bangkok to prepare an elaborate "50 Best Explores Thailand Gala

Dinner" to show how the project's crops could also become exquisite

cuisine.

"Opium production is highly labor intensive," said U.S.

anthropologist David Feingold, a former United Nations Educational,

Scientific, and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) official who also lived

and worked with Thailand's northern tribes.

"For the Akha people that I studied, it took 387 man-hours to

produce 1.6 kilos of opium. That was about 80 percent more than the

labor input into upland rice," Mr. Feingold said in an interview.

"So opium was not a terrific crop for the growers" but does enjoy

high value and low transportation costs.

"In an upland environment where transport is difficult and

expensive, this was important. Also opium was an important medicine,

it served as a currency...and was used to a certain extent

recreationally," mostly among older Akha males.

Poverty was more devastating than addiction, he said.

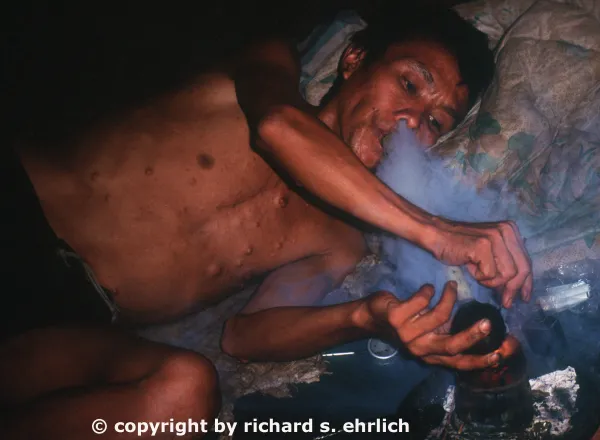

"With the Akha, they smoked mainly raw opium, essentially opium as

it comes out of the plant. In Southeast Asia, that opium has between 9

and 11 percent morphine content. Which means [smoking] down a pipe,

you are getting about one percent morphine content.

"There were people who had problems with abusing opium, just as

when you have lots of people who drink and you have people who have

problems with alcohol," he said.

"The crop replacement programs had additional side benefits in that

they brought certain services, like health services to hill tribe

villages," Mr. Feingold said.

In the 1300s, when Thailand was known as Siam, King U Thong outlawed opium.

In the 1800s, opium consumption soared across much of Asia after

British colonialists legally grew the poppies in India for massive

sales to China, and enforced those lucrative capitalist ventures by

fighting two Opium Wars.

The 1839-42 Opium War between London and Beijing defeated China's

attempt to ban British India's opium after too many Chinese became

junkies and the country hemorrhaged cash.

The 1856-60 Opium War stacked London and Paris against Beijing,

forcing a ruined China to cede Hong Kong to Britain and open five

coastal ports to foreign traders.

Bangkok reinforced opium's illegality in 1803 when King Rama I

decreed punishments for its use.

King Rama III tightened those bans and involved Buddhist clergy in

public "opium cremations."

But later in the 1800s, "the government of King Rama III began

importing opium from India and selling it by auction," according to

Cornell University's former Southeast Asia Program Director Thak

Chaloemtiarana.

"In the reign of Rama IV, opium use was restricted to the Chinese

community. Thais were not permitted to deal in or use opium. From that

time on, opium became associated with the rise of Chinese secret

societies," Mr. Tak wrote.

During World War II, "U.S. Air Force aircraft flew large quantities

of opium from India" to Burma to pay local tribal guerrillas fighting

against Japan's occupation, British officer Ian Fellowes-Gordon said,

according to historian Bertil Lintner.

"It was also necessary to enter the opium business," wrote U.S.

Office of Strategic Services Detachment 101's Commanding Officer in

Burma, Gen. William R. Peers, and his lieutenant Dean Brelis in their

book titled, "Behind the Burma Road: The Story of America's Most

Successful Guerrilla Force."

"Opium was available to [U.S.] agents who used it [for] obtaining

information [or] buying their own escape.

"If opium could be useful in achieving victory, the pattern was

clear. We would use opium," the American authors wrote.

Thailand's profitable, 100-year-old government-run Opium Monopoly

meanwhile began having import problems.

So Bangkok legalized some poppy growing in the north in 1947 by

allowing the Hmong, also known as Meo, to use their traditional opium

skills to raise the pod-headed stalks.

In China, communist Chairman Mao Zedong banished opium after

achieving victory in 1949.

But Southeast Asia's production rocketed because some of Chiang

Kai-shek's anti-communist, U.S.-backed Chinese Kuomintang (KMT)

guerrillas -- who lost their war against Mao -- fled into Burma, a

country now known as Myanmar.

KMT rebels raised funds by growing opium which they continued after

settling in northern Thailand.

In the 1950s, Thailand's U.S.-supported coup leader and military

dictator Gen. Sarit Thanarat, and his CIA-supplied rival Police Gen.

Phao Siyonon, competed to control the KMT's illegal opium exports.

Anti-communist Gen. Phao "became the CIA's most important Thai

client," wrote Alfred W. McCoy in his book titled, "The Politics of

Heroin in Southeast Asia."

"Phao protected KMT supply shipments [and] marketed their opium,"

Mr. McCoy wrote.

Gen. Sarit, who ruled from 1957 to 1963, soon ousted Gen. Phao and

declared opium totally illegal in 1959, partly to please the U.S. and

other foreign powers.

During America's wars against Laos and Vietnam in the 1960s and

70s, U.S.-backed corrupt officials in those Southeast Asian nations

made huge fortunes from opium and heroin while the CIA and regional

governments facilitated international smuggling with aircraft and

other assistance or ignored the evidence, according to Mr. McCoy.

"Production of cheap, low-grade, number 3 heroin -- three to five

percent pure -- had started in the late 1950s when the Thai government

launched an intensive opium suppression campaign that forced most of

her opium habitués to switch to heroin," Mr. McCoy said.

"By the early 1960s, large quantities of cheap number 3 heroin were

being refined in Bangkok and northern Thailand," he said.

In South Vietnam under President Nguyen Van Thieu and Premier

Nguyen Cao Ky, "the U.S. Embassy as part of its unqualified support of

the Thieu-Ky regime, looked the other way when presented with evidence

that members of the regime were involved in the [American soldiers']

G.I. heroin traffic," McCoy said.