This February, two major film institutions – the Pan African Film Festival and a movie museum – in Los Angeles, the world capital of cinema, honored Black History Month through the medium of moving images with screenings, presentations, panel discussions and more. Here’s the second of a two-part series.

THE ACADEMY MUSEUM OF MOTION PICTURES

Regeneration Summit

The Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences (AMPAS) built the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures, a repository of movie lore and history which opened in September 2021 and has exhibited Dorothy’s ruby slippers from The Wizard of Oz, the sled from Citizen Kane, the mechanical shark from Jaws, the severed horse’s head from The Godfather, and much more. This included the pioneering Regeneration: Black Cinema, 1898–1971, which co-curators Rhea L. Combs and Doris Berger describe as “the first large-scale exhibition… to examine the cmpellingly rich history of Black participation in American cinema, both inside and outside the Hollywood studio system,” in their 288-companion book to the installation, which seemed to be a response to the #OscarsSoWhite criticism that no Black thespians were Academy Award-nominated in the four acting categories in 2015. (See: https://progressive.org/latest/new-exhibit-atone-hollywood-past-rampell-092722/.)

Now the Academy Museum is extending this exhibit until July 16, 2023, and from February 3-5 the museum presented Regeneration Summit: A Celebration of Black Cinema, featuring workshops, screenings, panel discussions, authors signing relevant books in the Sidney Poitier Grand Lobby, live entertainment, and food vendors in the adjacent courtyard. According to a press release: “The summit will convene film artists, activists, musicians, and key people dedicated to preserving Black film history, including, Julie Dash, the Librarian of Congress Carla Hayden… Shola Lynch… and more. ” (See: https://www.academymuseum.org/en/programs/series/regeneration-summit-a-celebration-of-black-cinema.)

According to a press release, opening night featured: “The grandson of Cab Calloway, Joshua Langsam, and granddaughters of Fayard Nicholas, Cathie and Nicole Nicholas, join forces with musical accompaniment powered by multi-Grammy-award winning songwriter and record producer James Fauntleroy for a historic live performance honoring Cabell ‘Cab’ Calloway and the Nicholas Brothers.” Now, that’s entertainment! I covered two of the Summit’s symposia:

Political Power Grows Out of the Barrel of a Camera Lens: Regeneration Cypher: Activism in Film

This free form symposium on cinematic activism in the Academy Museum’s 288-seat Ted Mann Theater included: Senior Vice President of the Hollywood Bureau for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Kyle Bowser; founder of the Black Film Archive Maya Cade; Black non-binary activist Janaya Future Khan; filmmaker and storyteller Justice Maya Singleton (whose late father was John Singleton); and spoken word performances by actor and writer Roger Guenveur Smith.

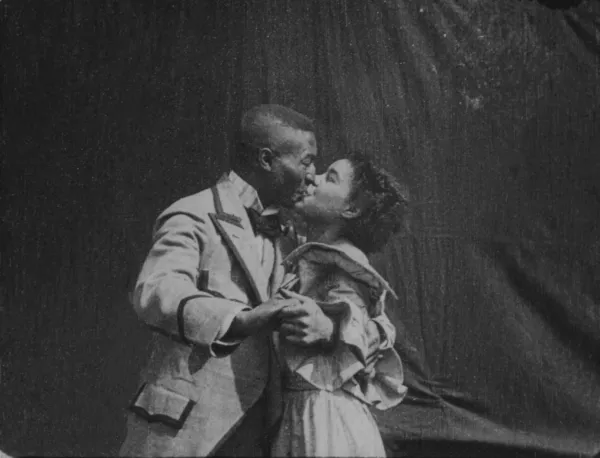

The NAACP’s Bowser most clearly and directly addressed the issue of “Activism in Film.” The longtime entertainment industry executive and attorney rather pithily stated: “The Civil Rights movement started in 1619,” and with his long view perspective, moved 300 years forward, on to the early days of cinema, citing the historical role of the 1915 silent film The Birth of a Nation. “Its production techniques are still used, but its storytelling sucks,” Bowser asserted. He referenced the stylistically innovative director D.W. Griffith’s creative use of cross-cutting, close-ups, rapid editing, etc., which are now essential elements of film form, and the tragic fact that Griffith’s artistry was put to the service of racist demagoguery in his troubling Civil War and Reconstruction Era epic, wherein the KKK literally rides to the rescue of lily-white Lillian Gish’s hymen threatened by a rapacious “mulatto” (portrayed, but of course, by a white actor in blackface).

Bowser went on to condemn The Birth of a Nation “in terms of its dehumanizing [and] otherized lifestyle… Griffith got the [stereotypical] parts started. President Woodrow Wilson [Griffith’s fellow Southern racist] showed The Birth of a Nation as the first film screened in the White House. There was a direct relationship – the Klan grew and lynchings increased,” inspired by Griffith’s bigoted blockbuster.

Actor Roger Guenveur Smith added, “It was a seminal moment in racist propaganda. We created an industry of our own, Black films for Black people,” by talents such as Oscar Micheaux, who is extolled in a gallery at the Academy Museum. Smith, whose long list of credits include Spike Lee’s 1989 Do the Right Thing and Nate Parker’s 2016 The Birth of a Nation – about the Nat Turner slave rebellion – went on to deftly deliver monologues, in character, as Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass and Anne Frank’s father Otto, throughout the activism symposium.

When asked to name your favorite film Janaya Future Khan cited Ivan Dixon’s 1973 The Spook Who Sat by the Door. Bowser likewise praised the screen adaptation of Sam Greenlee’s novel about the first African American CIA agent, who turns around and uses the covert skills the Agency taught him to wage urban guerrilla warfare against “whitey.”

How the West was Black: The Western

This excellent, more on point symposium also in the Ted Mann Theater featured actor/director Mario Van Peebles, Vassar College Professor of Film Mia Mask, Associate Curator of Western History at the Autry Museum Tyree Boyd-Pates, first generation equestrian and inventor of Mane Tresses Chanel Rhodes, and Executive Director of Urban Saddles Ghuan Featherstone. Each panelist explored the role of African Americans in the so-called “wild West” and in the Western movie, which is arguably the most American of all film genres.

Professor Mask, author of Black Rodeo: A History of the African American Western, which she signed in the Poitier Lobby during the Regeneration Summit, presented a top-notch slideshow detailing the history of Black cowboys, cavalry officers, settlers, cowgirls, ex-slaves with their Indigenous allies, and more. The extremely knowledgeable Prof. Mask’s superb presentation was as entertaining as it was educational and illuminating. Like Rawhide, her breezy, brisk delivery kept them doggies moving, and Mask’s well-timed pace reminded me of John Wayne on a cattle drive: “Let’s saddle up and move ’em out, pilgrims!” Mask regaled the audience with discussions of Sergeant Rutledge, Buck and the Preacher, Django Unchained, and so on. Professor Mask’s recitation was so great that when she left the stage, one couldn’t help but wonder, to paraphrase The Lone Ranger: “Who was that masked woman?”

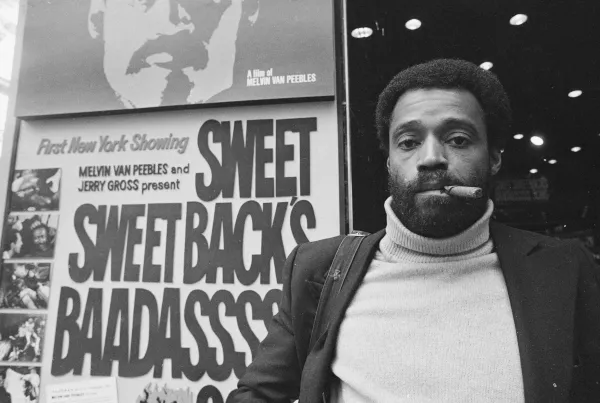

The Vassar scholar was a tough act to follow, but filmmaker Mario Van Peebles, who’d directed and starred in 1993’s Posse, was up to the task, as this cinematic storyteller is also a captivating raconteur in person. The actor/director enthralled the packed crowd, which he frequently cracked up with his anecdotes about making movies, including his upcoming period piece Outlaw Posse, with Whoopi Goldberg portraying Stagecoach Mary. But Van Peebles is more than a mere entertainer, he is also an artist, as well as a political thinker. The talent who directed 1995’s Panther, based on his father Melvin’s novel, and wherein Mario played Stokely Carmichael, referred to Frantz Fanon and declared: “The first step to control your mind is to control our imagery.” Precisely: Cinematic self-determination means that the self – not the outsider, the other – determines how the self is depicted.

The good fun and highly informative The Western panel concluded with a screening of the 1937 Western musical featuring a Black cast, Harlem on the Prairie, starring that Bronze Buckaroo, Herb Jeffries. The exciting experience of this symposium was enough to make one say: “Go West, young man – and woman!” (For more information about the Regeneration Summit’s February 4 symposia see:

https://www.academymuseum.org/en/programs/detail/saturday-symposium-regeneration.)

AMPAS seems to be taking to heart the racial criticism leveled against it in 2015 (exactly a century after The Birth of a Nation stirred so much controversy) and beyond, and the Academy Museum of Pictures is shining a klieg light on the achievements and history of Blacks onscreen. This may be a case study in how protest can alter the course of major institutions to be more inclusive and culturally sensitive. With film scholar extraordinaire Jacqueline Stewart – Director and President of the Academy Museum, as well as a Turner Classic Movies host – at the helm, this reliquary of all things cinematic will hopefully continue to make history by zooming in on long overlooked ethnic groups and their contributions to moving pictures.

NOTE: The Academy Museum is commemorating the 75th anniversary of the Hollywood Blacklist. To see the schedule go to: https://www.academymuseum.org/en/programs/series/the-hollywood-ten-at-75.