There are three great acts of naval rebellion in nautical history and the one that’s been the least celebrated in popular culture – until now – is (finally!) the subject of Trouble the Water. Ellen Geer’s stage adaptation of Rebecca Dwight Bruff’s 2019 novel of the same name dramatizes the remarkable real-life saga of Robert Smalls, who was born enslaved in 1839 and rose to become one of the Civil War’s great heroes and among America’s first Black Congressmen, initially elected during the Reconstruction Era.

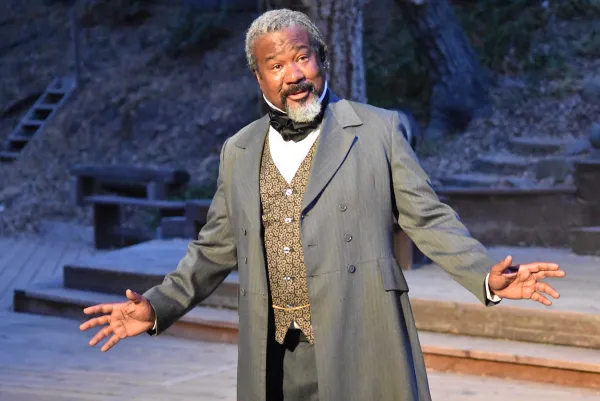

Smalls’ stunning story is so phenomenal that it takes no less than two thespians to depict this Black Spartacus: A simmering Terrence Wayne, Jr. (whose credits include Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum’s production of Ibsen’s Enemy of the People) as the youthful slave-turned-revolutionary aptly nicknamed “Trouble,” and Gerald Rivers as the postwar Republican statesman who, having met Honest Abe during the Civil War, may have coined the phrase that refers to the GOP as “the party of Lincoln.” Rivers, a WGTB stalwart and, quite appropriately, a renowned Martin Luther King reenactor, also directs Trouble the Water.

Trouble grew up in the town of Beaufort, South Carolina, where his mother Lydia Polite (Earnestine Phillips, a three-time NAACP Theatre Award winner and WGTB veteran, from Shakespeare plays to To Kill a Mockingbird) served in the household of the married Caucasian couple Henry (Alistair McKenzie) and Jane McKee (Robyn Cohen) as what was called a “house servant” (although she was enslaved) or “House Negro” (or, often, the “N” word was used in the antebellum South and is occasionally uttered onstage during Water – although never gratuitously, as it often has been in productions, from music videos to the dubious HBO show Insecure).

One of my favorite things about dramatizations is how the long ago and far away can be brought back to life again for contemporary audiences. When dealing with actual historical personages such as Smalls, I feel that productions should hew closely to accuracy and fidelity to the spirit, if not always the letter, of the characters and events depicted in a biopic or bioplay. Water is fascinating in that it reenacts what America’s seventh Vice President, racist scumbag John C. Calhoun, called the “peculiar institution” of slavery.

Today, while overt chattel slavery no longer per se exists, there is much talk of “institutionalized racism,” which is the descendent and 21st century perpetuator of the legacy of plantation bondage and Jim Crow. Viewing Water, it’s captivating to see how the enslaved Blacks interact with the whites. On the one hand, beyond the lies generated by racism, there is still the human interaction of people who are often in close quarters with one another. McKee shows a fatherly interest in Trouble and goes fishing with the lad, whom he clearly harbors affection for.

Yet, according to South Carolina’s laws at the time, Lydia and Trouble also belonged to McKee. As his property, they were not fully recognized as human beings (only as “three fifths” of a man/ woman!). In those dark decades more than 160 years ago, long before “workplace harassment” laws and the #MeToo and Black Lives Matter movements, it is suggested that McKee took advantage of Lydia by using his legally superior position entrenched in the power structure to coerce his piece of “property” to surreptitiously have sex with him. (As if unpaid for labor wasn’t insulting and injurious enough!)

(A leitmotif of Water is the mystery as to who Trouble’s biological father was, and the play suggests perhaps McKee was. This subplot of Robert seeking to know who his real father was could be dubbed “From Here to Paternity.”)

Jane undergoes some consciousness-raising and realizes that even if she is white, as a woman she, too, has limited rights and is, indeed, also a form of property owned by her husband. However, the journal she keeps is likely a device conjured by the author’s use of dramatic license, and Jane’s ultimate fate as dramatized in the play’s finale is also historically unsubstantiated. (See Bruff’s candid comments at: https://rusoffagency.com/book-info/the-story-behind-the-book-111/). Jane’s pro-feminist and anti-slavery musings hint at the 19th century alliance between suffragettes and abolitionists, but one wonders how historically accurate this is, and whether the presumably woke women who wrote the novel and script of Trouble the Water are actually injecting their 21st century worldviews into their antebellum character’s mouth?

If the McKees are the “good massas” in the mode of Uncle Tom Cabin’s Augustine St. Clare, the hardline slaveowner Robert Barnwell Rhett (an imperious Franc Ross) and his son Peter (a bullying Ethan Haslam) are the counterparts to the viciously cruel Simon Legree in Harriett Beecher Stowe’s 1852 classic. After Trouble experiences life firsthand as a field hand and clashes with the wicked Rhetts, Henry McKee allows the enslaved Smalls to work in Charleston, with most of his wages being turned over to his owner, which leads to Trouble’s realization that he is an exploited worker. In the city Trouble meets his future wife Hannah (Tiffany Coty, who also acted in another Black-themed WGTB production about fighting “whitey,” Haiti), teaches himself how to read and rises from serving in a restaurant to working on the waterfront, where he gains intimate knowledge of Charleston’s waterways and how to navigate and operate ships.

The latter is essential for the unfolding of the all-too-true plot in Act II. In 1862, Smalls rather boldly commandeers the CSS Planter, a Confederate warship loaded with artillery and ammunition. With a heroic band of enslaved sailors and their families, Smalls craftily pilots the converted steamer through the treacherous Confederate waters, past the vigilant force at Fort Sumter (Smalls was likely an eyewitness to the April 12-13, 1861 bombardment there of Federal troops that ignited the “War Between the States”), towards Union ships blockading Charleston. There, Trouble and his brave band of fellow “Good Troublemakers” succeeded in turning over the appropriately named Planter to the U.S. armada, along with its precious cargo of armaments plus, according to Wikipedia, “the captain’s code book containing the Confederate signals and a map of the mines and torpedoes that had been laid in Charleston’s harbor.”

According to the play, Trouble was monikered “Smalls” by other enslaved individuals because of his height. Be that as it may, standing at only five-foot and five inches, Smalls was both David – and Goliath. A true giant among men of any color, with his direct militant action Robert “Trouble” Smalls is a shining beacon for the wretched of the Earth who want to turn the pigs who oppress them into bacon. Smalls went on to meet with Pres. Lincoln and helped convince the administration to allow African Americans to serve in the U.S. military in order to defeat Southern slavery. Hailed as a hero, Robert himself joined the U.S. armed forces and participated in many Civil War battles.

After the secessionists were beaten, Smalls continued his service to his people as a legislator, on the state and Federal level during and beyond Reconstruction. When I was around 12-years-old I attended a screening at the Museum of Modern Art of D.W. Griffith’s 1915 racist Civil War era epic The Birth of a Nation, which was followed by a historian’s slide show presentation. In the latter the presenter projected frames from Birth, including Griffith’s depiction of South Carolina legislators in the State House of Representatives, which a screen title labels as “An Historical Facsimile,” wherein the mostly Black legislators are portrayed as buffoonish, drinking liquor, eating fried chicken, removing their shoes and propping their bare feet up on their desks in the legislative chamber. According to Griffith, who was obsessed with African American male sexuality, among the laws these Radical Republican Blacks pass during this Reconstruction era legislative session is the right to intermarriage, which causes the Blacks to wildly rejoice.

I’ve never forgotten that the historian presenting the slideshow at MOMA then went on to reveal the numerous progressive bills that were, in real life, voted on by this largely African American legislature. Among them was the first free and compulsory school system in America – which was authored by the self-taught Robert Smalls, who was then one of those South Carolina state lawmakers who Griffith derided and ridiculed in his pro-KKK agitprop. It seems that D.W. – along with his fellow rabid racists – needed to be sent back to school to get a proper education.

If you have a strong stomach, you can see Griffith’s celluloid stereotypes of South Carolina’s Black legislature at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8uuCMA-yE64. You will likewise need intestinal fortitude to see this hard-hitting drama, which includes depictions of rape, lynching, fighting, offensive language and more. (A little birdie told me that the director cut a scene portraying a KKK meeting.) But despite the strong subject matter, I believe theatergoers will be richly rewarded if they “jump the broom” and take the trouble to go see Trouble the Water. As the elder Smalls insists at the end: “It’s time we tell the truth.” Reuben (Clarence Powell in multiple roles), who is lynched, repeats the Biblical edict that “The truth shall set ye free.” As the furor over school curriculums, the dreaded, demonized “CRT”, etc., besets our public discourse, productions like Water that unearth and resurrect forgotten yet essential episodes from our hidden history is all the more important – lest the South, so to speak, rises again…

As powerful as the content is, Water is related in an entertaining way. With a cast of about 26 players, Gerald Rivers’ mise-en-scène extends beyond WGTB’s mostly bare stage, sprawling along Topanga Canyon, the hollow where this hallowed amphitheater is perched. Costume designer Yuanyuan Liang’s garb enhances the historical sense of this period piece. The Street Corner Renaissance Choir enlivens the proceedings with a series of mostly gospel songs performed by a quintet of Black males. This a cappella group performs from on high, on a stage right landing, and includes Maurice Kitchen, who was the writer/director/producer of Voices: A Legacy to Remember, an NAACP-Image Award nominated production about the trials, tribulations, travails and triumphs of African Americans that I experienced at the Wilshire Ebell Theatre in 2010 (see: https://www.laprogressive.com/progressive-culture/voices-sizzling-sag).

Movie director Charles Burnett reportedly has a biopic about Robert Smalls in the works, but with the novel and now the premiere of the play Trouble the Water, at long last the stirring story of Smalls’ seizure of a Confederate ship is being told in popular culture. This dramatization finally joins those other outstanding acts of nautical rebellion celebrated by mass entertainment. In 1925, Sergei Eisenstein directed the immortal film Potemkin, about sailors who stage a mutiny aboard a czarist battleship during the Russian Revolution of 1905 at Odesa – where my own ancestors are from.

Of course, the most romanticized episode of rebellion on the high seas was captured on the page and onscreen in various versions depicting the mutiny on the Bounty, when British sailors in the South Pacific seized their vessel and threw the tyrannical Captain Bligh overboard in 1789 (the same year as the French Revolution, lest we forget!). James Norman Hall and Charles Nordhoff’s bestseller was adapted for the big screen in 1935 and 1962, starring Clark Gable and Marlon Brando as the mutinous Fletcher Christian. There have been other movie iterations of the Bounty saga, including 1933’s In the Wake of the Bounty featuring Errol Flynn as Fletcher in his screen debut and Mel Gibson as Fletcher Christian in 1984’s The Bounty. I’m scheduled to fly to Tahiti soon where I’ll board the cargo-cruiser Aranui and sail through French Polynesia’s most remote isles and atolls all the way to Pitcairn Island, the uncharted isle 1,000 miles east of Tahiti the mutineers and their Polynesian sweethearts stumbled upon in 1790 – and where their descendants still live. (For details see: https://www.aranui.com/en/itinerary/?itineraire=in-the-footsteps-of-the-bounty-mutineers-pitcairn-gambier-2022&depart=2022-10-22.)

Until Burnett or a contemporary Eisenstein film the Robert Smalls story and it joins the Bounty and Potemkin on the big screen, viewers have the rare opportunity to go to the must-see Trouble the Water through Oct. 2, where it will run in repertory with A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merry Wives of Windsor and The West Side Waltz at Will Geer’s Theatricum Botanicum,1419 N. Topanga Canyon Blvd., Topanga CA 90290 (midway between Pacific Coast Highway and the Ventura Freeway). For info: (310)455-3723 or www.theatricum.com. It can get chilly at night in the open-air amphitheater, so dress warmly. Pandemic protocols are observed, so bring proof of vaccination. For more information about the historical Robert Smalls, read Prof. Henry Louis Gates’ account at: https://www.pbs.org/wnet/african-americans-many-rivers-to-cross/history/which-slave-sailed-himself-to-freedom/.