A Way of Liberation How Will We Challenge Militarism, Racism, and Extreme Materialism?

This is an exposition of the photographic essay by William Pepper about the children of Vietnam that Martin King first saw on January l4, l967. Initially, while he hadn’t had a chance to read the text, it was the photographs that stopped him. As Bernard Lee who was present at the time said, “Martin had known about the [Vietnam] war before then, of course, and had spoken out against it. But it was then that he decided to commit himself to oppose it.” Pepper’s essay contains the most powerful creative energy on earth: truth force. It is as relevant 50 years later as it was in 1967. Martin King steadfastly exhorted all to confront and grapple with the triple prong sickness—lurking within the U.S. body politic from its inception—of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism. These evils require us to respond with life-giving intelligence, to change course away from the nightmare path we are pursuing, and towards, in Coretta King’s words, “a more excellent way, a more effective way, a creative rather than a destructive way.” All of us in the United States are the ones best positioned to challenge the destructiveness of the three prong sickness destroying our civilization and the Earth, and change direction towards affirming life in all its variations and sacredness. We have choices and power here that the majority of humanity do not enjoy. The choice and the power resides with us. And the choice to recognize that power, and take responsibility for it to make this into a world where all of us can live together in peace and fellowship s i t s r i g h t h e r e.

Within the United States we are constantly told this is the greatest country on Earth and the last, best hope of humanity. In order to live up to such lofty assertions, it is necessary for all U.S. citizens to understand what is being done in our collective name every single day. Such awareness requires a willingness to confront disturbing and frightening facts that challenge the popular slogans of the land of the free and the home of the brave.

Following reports in the 1980s of the U.S. -armed, -funded, and -trained death squads in Central America, the thought kept surfacing: ‘If only people in the U.S. could see factual footage of how our government is directly and covertly involved in on-the-ground torture and murder of innocent people south of the U.S. border, they would en masse demand it stop.’ There are many articles and books that catalog and enumerate sources concerning post-WWII United States military aggressions and intelligence agency covert operations both domestic and foreign.[1] The focus here is an especially potent photographic essay on the consequences to the people of Vietnam from the U.S. war in their country.

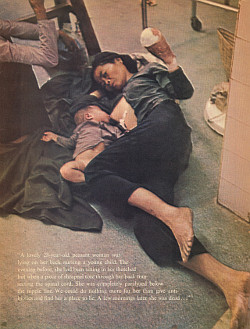

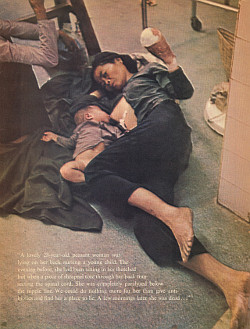

“A lovely 28-year-old peasant woman was lying on her back nursing a young child. The evening before, she had been sitting in her thatched hut when a piece of shrapnel tore through her back transecting the spinal cord. She was completely paralyzed below the nipple line. We could do nothing more for her than give antibiotics and find her a place to lie. A few mornings later she was dead.”

In January 1967, an article was published in Ramparts Magazine by William Pepper titled, “The Children Of Vietnam.”[2] This searing essay presented vital historical truth of the toll the U.S. war in Vietnam was taking both physically and psychically on that country’s children. At the time Pepper was executive director of the New Rochelle Commission on Human Rights, an instructor in Political Science at Mercy College in Dobbs Ferry, New York, and director of the college’s Children’s Institute For Advanced Study and Research. On leave of absence in the spring of 1966, he spent six weeks in Vietnam as a correspondent accredited by the Military Assistance Command in that country, and by the government of Vietnam. His primary concern was the effects of the war on women and children, the role U.S. voluntary agencies performed, and the work of the military in civil action.

The time period in which “The Children of Vietnam” was written included a wide-spread and expanding anti-war movement that increased pressure on the U.S. federal government which finally ended its war in Vietnam in 1973. It might have ended it in 1968 had Presidential candidate Richard Nixon not committed treason by secretly offering the North Vietnamese a better deal if they waited until after he won the November election.[3]

It would have ended in the mid-1960s. Tragically, the assassination of President Kennedy aborted the formal decision he had made to withdraw all U.S. military forces from Vietnam by the end of 1965. James Galbraith described this in a 2009 interview:

Vincent Browne: Your father of course was very close to John F Kennedy... Some of our viewers may not know this, John Kenneth Galbraith was a very famous American. He was an economist, and a brilliant economist at that, but he also was well known generally. He became the ambassador to India, appointed to India by John Kennedy in 1961, and was quite close to Kennedy. Though why he was sent so far away to India, what he thought, I wonder.

James K. Galbraith: The reason for that was in part that he wanted my father involved on foreign policy, in particular to be an effective independent voice on Southeast Asia, on Vietnam. That played an important role in Kennedy’s thinking on those issues.

VB: And yet Kennedy is blamed quite a bit for building up American forces in Vietnam and starting that enterprise. Do you think that’s fair?

JKG: The reality was that my father was an opponent from the very beginning of the commitment of U.S. forces to Vietnam. McNamara and Kennedy agreed with him on that point. A policy was put into place to end the U.S. involvement in Vietnam and a formal presidential decision was taken in October of 1963 that would, if implemented, have caused a full pullout of U.S. forces from Vietnam by the end of 1965. That is the historical record.

VB: So you believe that Kennedy would have withdrawn the U.S. forces from Vietnam then.

JKG: What he did was to make a formal decision to do so. So it’s not a question of belief of what he would have done. It’s a question of establishing, as a point of historical fact, what he did decide to do. And it’s clear that he did. We have all of the documents involved in the making of the decision including the decision itself and including, actually, tapes of Kennedy ordering that decision to be taken. So the record is now very firmly established and the surviving participants, including Secretary McNamara, fully agree that that was in fact the decision that President Kennedy took.[

4]

The formal decision of President Kennedy to implement a full withdrawal of U.S. forces from Vietnam by 1965 was made less than two months before Dallas. In his November 2009 Keynote Address at the Coalition on Political Assassinations conference, Catholic Worker and author Jim Douglass spoke about this.

On October 11, 1963, President Kennedy issued a top-secret order to begin withdrawing the U.S. military from Vietnam. In

National Security Action Memorandum 263, he ordered that 1,000 U.S. military personnel be withdrawn from Vietnam by the end of 1963, and that the bulk of U.S. personnel be taken out by the end of 1965.[

5]

Kennedy decided on his withdrawal policy, against the arguments of most of his advisers, at a contentious October 2 National Security Council meeting. When Defense Secretary Robert McNamara was leaving the meeting to announce the withdrawal to the White House reporters, the President called to him, “And tell them that means all of the helicopter pilots, too.”[6] Everybody is going out.

In fact, it would not mean that at all. After JFK’s assassination, his withdrawal policy was quietly voided. In light of the future consequences of Dallas, it was not only John Kennedy who was murdered on November 22, 1963, but 58,000 other Americans and over three million Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians.[

7]

National Security State historian John Judge devoted his life to research, writing, and speaking.[8] In Kenn Thomas’s words, “Judge compiled data and ferreted out information about the oft covered-up facts of history.”[9] John grew up in Falls Church, Virginia where both his parents, John Joseph Judge and Marjorie Cooley Judge worked as civilian employees in the Pentagon. As he recounted in a 2002 talk:

[M]y mother was the highest-paid Pentagon employee for more than almost all of her thirty years career in the Pentagon. But for many, many years, the highest paid employee under the Joint Chiefs of Staff. Directly under the Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel, my mother’s job was to project the draft call. She had to project for the Joint Chiefs how many do they have to draft in order to keep the force level at where the Joint Chiefs wanted it to be. They would give her statistical tables based on their experience: How many would retire? How many would die of natural causes? How many would reenlist? How many would discharge under each category? How many would enlist anew? And therefore to have whatever force level they wanted up or down, how many did you have to draft? She had to project that annually and nationally and those calls got upwards of 50,000 a year. She had to project it annually and nationally right and accurately enough to be within a hundred people either way on the call. And I remember her sweating them coming in. Those projections had to be made that accurately five years in advance. Five years in advance.

They projected it, and whatever number my mother said they needed they multiplied it by five, she told me, and sent it to the Select Service System as its quota. Why? Because fifty to fifty-five percent would flunk a physical; ten to fifteen percent would fall under a deferment or exemption; another ten to fifteen percent would no show or refuse. And then they were back to the twenty percent they needed in the first place. They planned it.

So I asked my mother after she retired, When did they tell you they would escalate the war in Vietnam? Because she had to be among the first to know. She told me that in April of 1963, for the first time in her career at the Pentagon, she was told to reverse her projections, to change her projections. She’d never been asked to do that before. She said it was on orders from the White House, which meant it was on orders from John F. Kennedy. She was told to change the projections to reflect a full withdrawal of American troops from Vietnam by the end of 1964. She put those figures into the projections.

I said, When did they tell you they would escalate? She said the last week in November. I said, Late November, last week—I said—Kennedy’s killed Friday the 22nd of November in 1963. She said, The Monday following the assassination. He’s barely in the grave and she’s given figures and my mother couldn’t believe the figures. My mother told me she took the figures back up to the Joint Chiefs and she said, These can’t be right. And they told her to use them. I used to tease her that that was the first civilian protest of the war in Vietnam.

The figures she was given on November 25th ’63 was that the United States was entering into a ten-year war in Vietnam with 57,000 American dead. Exactly on target. Till ’73: fifty seven thousand five hundred names on the wall. They know where they’re going. They plan ahead.[10]

Over three million Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodian as well as 58,000 U.S. American lives were lost as a direct result of the assassination of the 35th President. The war that would finally end in 1973 was being put on rails to end ten years earlier. Collectively, U.S. state actors, academicians, and media personnel have not yet confronted, much less acknowledged, the truth concerning our history of this timeline.

It’s that everything [in the Cold War in 1962-1963] was totally out of control and then, through a kind of incredible process where these two men were communicating secretly with each other over the year previous [Sep 1962-63], and smuggling letters back and forth to each other, in the midst of this conflict, they were beginning to trust each other.... It’s a remarkable process. And it’s all beneath the surface. But so are all the things that count as Merton understood.... And that’s why I have some hopes that if we are willing to go deeply enough into the darkness—and Kennedy was, and Khrushchev was—anything can happen for the good. But if we don’t go into the darkness it doesn’t happen.

Jim Douglass at Elliot Bay Books, Seattle, May 6, 2008, at

53:40.

Who benefited from the prospective eight additional years of that war? Certainly not the indigenous peoples of southeast Asia. Beyond the number of dead in Vietnam, those who survived faced a more pernicious horror as the opening of “The Children of Vietnam” explains.

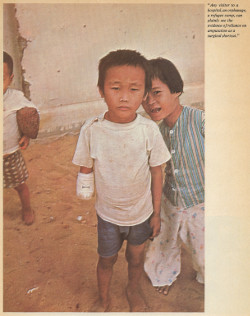

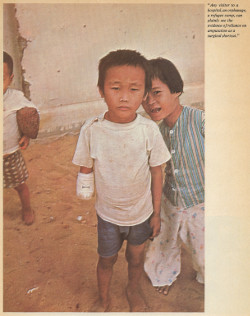

“Any visitor to a hospital, an orphanage, a refugee camp, can plainly see the evidence of reliance on amputation as a surgical shortcut.”

For countless thousands of children in Vietnam, breathing is quickened by terror and pain, and tiny bodies learn more about death every day. These solemn, rarely smiling little ones have never known what it is to live without despair.

They indeed know death, for it walks with them by day and accompanies their sleep at night. It is as omnipresent as the napalm that falls from the skies with the frequency and impartiality of the monsoon rain.

The horror or what we are doing to the children of Vietnam—“we,” because napalm and white phosphorus are the weapons of America—is staggering, whether we examine the overall figures or look at a particular case like that of Doan Minh Luan.

Luan, age eight, was one of two children brought to Britain last summer through private philanthropy, for extensive treatment at the McIndoe Burns Center. He came off the plane with a muslin bag over what had been his face. His parents had been burned alive. His chin had “melted” into his throat, so that he could not close his mouth. He had no eyelids. After the injury, he had had no treatment at all—none whatever—for four months.

It will take years for Luan to be given a new face (“We are taking special care,” a hospital official told a Canadian reporter, “to make him look Vietnamese”). He needs at least 12 operations, which surgeons will perform for nothing: the wife of a grocery-chain millionaire is paying the hospital bill. Luan has already been given eyelids, and he can close his mouth now. He and the nine-year-old girl who came to Britain with him, shy and sensitive Tran Thi Thong, are among the very few lucky ones.

There is no one to provide such care for most of the other horribly maimed children of Vietnam; and despite growing efforts by American and South Vietnamese authorities to conceal the fact, it’s clear that there are hundreds of thousands of terribly injured children, with no hope for decent treatment on even a day-to-day basis, much less for the long months and years of restorative surgery needed to repair ten searing seconds of napalm.

When we hear about these burned children at all, they’re simply called “civilians,” and there’s no real way to tell how many of them are killed and injured every day. By putting together some of the figures that are available, however, we can get some idea of the shocking story.

In February 2003 William Pepper spoke at Modern Times Bookstore in San Francisco on the release of his new book, An Act of State: The Execution of Martin Luther King. He started his talk by relaying his experience in Vietnam.

This story actually begins with Vietnam in 1966. As a very much younger person I was there as a journalist and didn’t publish anything whilst I was there, but waited until I got back to the United States. Then I wrote a number of articles. One of them appeared in a muckraking magazine called Ramparts, that had its home in this city, published by Warren Hinkle in those days. It was called “The Children of Vietnam.” That is what started me down the slippery slope of the saga of Martin Luther King; his work during the last year, and his death. And then an investigation which has gone on since 1978.[11]

In 1964 Wayne Morse (D-OR) was one of only two U.S. Senators to oppose the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution which authorized LBJ to take military action in Vietnam without a declaration of war. In remarks before the Senate on August 22, 1966, Morse spoke at length about William Pepper and his experiences in Vietnam the previous spring:

As Mr. Pepper makes clear, by far the majority of present refugees in South Vietnam have been rendered homeless by American military action, and by far the majority of hospital patients, especially children, are there due to injuries suffered from American military activities. The plight of these children and the huge burden they impose upon physical facilities has been almost totally ignored by the American people.[12]

In a 1999 essay, Jim Douglass writes how:

The final chapter of Martin Luther King’s life began on January l4, l967, the day on which King committed himself to deepening his opposition to the Vietnam War. He was at an airport restaurant on his way to a retreat in Jamaica. While looking through magazines, he came across an illustrated article in Ramparts, “The Children of Vietnam”. His coworker Bernard Lee never forgot King’s shock as he looked at photographs of young napalm victims.[13]

He froze as he looked at the pictures from Vietnam. He saw a picture of a Vietnamese mother holding her dead baby, a baby killed by our military. Then Martin just pushed the plate of food away from him. I looked up and said, “Doesn’t it taste any good,” and he answered, “Nothing will ever taste any good for me until I do everything I can to end that war.”

Bernard Lee later explained, “That’s when the decision was made. Martin had known about the war before then, of course, and had spoken out against it. But it was then that he decided to commit himself to oppose it.”[14]

Continuing in his 2003 talk, Pepper described how he began to work with Martin King:

“Torn flesh, splintered bones, screaming agony are bad enough. But perhaps most heart-rending of all are the tiny faces and bodies scorched and seared by fire.”

Then he asked to meet with me and asked me to open my files to him that went well beyond what was published in the Ramparts piece in terms of photographs. Some of you probably saw, if you’re old enough to remember, a number of those photographs. Portions of them used to appear on lampposts and windows of burned and deformed children. That was what gave him pause. He hadn’t had a chance to read the text at that point but it was the photographs that stopped him.

The introduction of the article was by Benjamin Spock. It resulted, ultimately, in a Committee of Responsibility bringing over a hundred Vietnamese children, war-injured children to this country and our placing them in hospitals around the nation. This was so that people would have a chance to see first-hand what their tax dollars were purchasing.

On the way to Cambridge to open Vietnam Summer, an anti-war project, we rode from Brown University (where he had delivered a sermon at the chapel there) and I continued the process of showing him these photographs and anecdotes of what I had seen when I was in the country. And he wept, he openly wept. He was so visibly shaken by what was happening that it was difficult for him to retain composure. And of course that passion came out in his speech on April 4th, 1967 at Riverside Church where he said that his native land had become the greatest purveyor of violence on the face of the earth. Quoting Thoreau he said we have come to a point where we use massively improved means to accomplish unimproved ends and what we should be doing is focusing on not just the neighborhood that we have created but making that old white neighborhood into a brotherhood. And we were going entirely in the opposite direction and this was what he was pledging to fight against.

We spoke very early in the morning following that Riverside address and he said, “Now you know they’re all going to turn against me. We’re going to lose money. SCLC [Southern Christian Leadership Conference] will lose all of its corporate contributions. All the major civil rights leaders are going to turn their back on me and all the major media will start to tarnish and to taint and to attack me. I will be called everything even up to and including a traitor.” So he said, “We must persevere and build a new coalition that can be effective in this course of peace and justice.”[15]

As William Pepper recounted, when Martin King first saw “The Children of Vietnam,” “He hadn’t had a chance to read the text at that point but it was the photographs that stopped him.” The profound force of truth in the images of U.S. war consequences to the people of Vietnam moved Dr. King to begin, in Gandhi’s words, his final experiments in truth.[16]

Vincent Salandria describes how “historical truth is the polestar which guides humankind when we grope for an accurate diagnosis of a crisis.”[17] Jim Douglass relays how Gandhi’s experiments in truth take us into the most powerful force on earth and in existence: truth force or satyagraha. “Remember what Gandhi said that turned theology on its head. He said truth is God. That is the truth: Truth is God. We can discover the truth and live it out. There is nothing, nothing more powerful than the truth. The truth will set us free.”[18]

“The Children of Vietnam” provides an instance of truth force that is needed now more than ever to counter the fragmentation and doublethink being amplified by the demands of capital and its accumulation. Because, tragically and horrifically, what the United States caused to happen in Vietnam has not stopped. It continues to this day, magnified on a global scale within numerous theatres of U.S. military and covert operations including in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and Yemen.[19]

Earlier this month a report from the Costs Of War project at Brown University details U.S. spending on post-9/11 wars to reach $5.6 trillion by 2018.[20] Among other data, this series finds that the average U.S. taxpayer has spent $23,386 on these wars since 2001. Apprehended in this way, it is clear how each of us who pays taxes in the U.S. is collaborating in, and contributing to, the militarism that is devastating the globe and devouring our collective future.

In denouncing the U.S. war in Vietnam at Riverside Church in 1967 Martin King posed the question on behalf of Vietnamese peasants: “What do they think as we test out our latest weapons on them, just as the Germans tested out new medicine and new tortures in the concentration camps of Europe?” And this was a war that ended up being broadcast on nightly news television in the United States as it became evermore hellish in its results. Said King at Riverside, “When machines and computers, profit motives and property rights, are considered more important than people, the giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism are incapable of being conquered.” His voice, love, compassion, and intelligence are as searingly relevant right now, half a century later, as in 1967.

Historian Vincent Harding was a close friend of Martin King and the author of King’s “Beyond Vietnam: A Time to Break Silence,” speech at Riverside Church. In his uncompromising book, Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero,[21] Harding offers a series of meditations on the final years of King’s life after his August 1963 I Have A Dream speech. In a 2010 conversation, the historian described how, for the U.S. to establish a national MLK holiday,

Martin would have to be somewhat domesticated in order for the country to deal with him because he was...calling us to give up for instance on the whole experience and teaching and living of white supremacy, calling us to move away from the great levels of materialism that have always been so much a threat to our humanity and the humanity of others.... Almost never in most of the [national holiday] celebrations is there any lifting up of his powerful statement against the war and against the machinery of war and against militarism and against our temptation to live as a new kind of imperial power in the world.[22]

Harding’s book evokes and reignites the increasingly radical King, largely forgotten, rejected, and ignored by the status quo at every level. Writing of the national holiday, he asks the question,

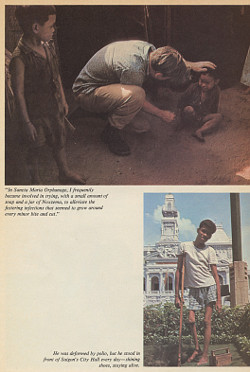

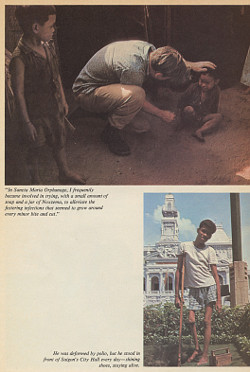

“In Sancta Maria Orphanage, I frequently became involved in trying, with a small amount of soap and a jar of Noxzema, to alleviate the festering infections that seemed to grow around every minor bite and cut.”

He was deformed by polio, but he stood in front of Saigon’s City Hall every day—shining shoes, staying alive.

When will he be safely dead? Listen for him in January.... Hear the voices from the black past (and future) singing, beyond the “Hosannas,” singing with Martin, for Martin, “Ain’t no grave can hold my body down.”

Perhaps the youngest children will hear best, will receive the voices and the songs through ears and hearts not yet filled with the “Top Forty,” through eyes that see beyond MTV and other diversions from getting ready. Perhaps they will sense that great men and women do not really die. Perhaps they will ask about his dream, his cause, suspecting that he lives, somewhere, nearby. Perhaps we will have the wisdom, the knowledge, and the courage to introduce them to the hero who, by the end of his life, was totally committed to the cause of the poor—in Mississippi, in Chicago, in Appalachia, in Vietnam, in Central America, in South America, in Memphis.

Perhaps we will tell them that the older dream, the famous, easier-to-handle dream, the forever-quoted dream of 1963 was no longer sufficient for him. Let them know that at the end, when the bullet finally came, he was dreaming of marching on Washington again, but this time to stay there, not just for speeches and for singing, but for audacious, challenging, divinely obedient action—to engage in a campaign of massive civil disobedience to try to stop the functioning of the national government. Tell them he planned to do this, calling on thousands and hundreds of thousands of lovers of justice until the cause of the poor became the nation’s first priority, until all people were guaranteed jobs or honest income, until our nation stopped killing Asians abroad and turned to tend to the desperate needs of its people at home.[23]

Published in 1996, Harding reminds us of the bristling vector Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was accelerating towards, unceasing in his invitation for all to likewise walk through the self-imposed walls of our own limitations and to create and establish “another way, a better way than the way of weapons and war, to be all [we] can be.”[24]

Getting ready is letting the shouts, the accusations, the condemnations cascade over us, enter deep, breaking through the walls, getting under the skin, flaming up the cool. Getting ready, for some of us, is especially hard sometimes, for some times it is being black and understanding that poetry is timeless. It is facing the possibility that now, years later, years of “progress” and “equal opportunity” and getting our piece, and swimming in the main one, and sitting paralyzed in front of television for hours at a stretch every impressionable childhood day—that now the screaming, revival-time words might be not just for white folks, but also for us, for us, to warn us of how fearful we are now, today (so many years after the Memphis balcony). How terrified, how guarded we have become against all that Martin King was called then in his last, beleaguered years: “agitator,” “trouble-maker,” “radical,” “communist-sympathizer,” “fanatic,” “unpatriotic,” “un-American,” “naive,” “dangerous” to the status quo.

Do we dare fantasize about what we would do now, if he came to our black-administered city, to challenge our leaders; if he tried to question our values, and our bank accounts, and our political machine; if he dared to undermine the morale and question the Christian faith of our soldiers, of our officers, of our chaplains—as they landed in Grenada, as they poised themselves on the borders of Nicaragua, as they enjoyed equality of opportunity to press the buttons of nuclear destruction, as they prepared for possible duty fighting “the communists” on behalf of the government of South Africa?

Are we, too, now frightened by people who organize unkempt and unrespectable folks to struggle for peace and justice here and abroad, who now take risks to do for escaping Central Americans what the Underground Railroad did for us—while we stand back, as far back as possible? Are we, too, now frightened in our respectable blackness by all the strange folks who, with King, really believe the way of love is more faithful to Jesus of Nazareth than the well-paid “defense” occupations of war-making, war-thinking, war-threatening, and death? Do we, too, mock democracy each time we back away, each time we fail to participate actively in the struggles for the transformation of our institutions and of this nation, in the defense of the poor, in the protection of the environment, in the questioning of our political leaders, in the teaching of ourselves and our children who the hero really was—and who he, and we, may yet become?[25]....

He dreamed a world where all were free to serve their sisters and brothers in compassion and hope, where fear had no dominion, where the resources of the nation were redistributed to meet the needs of the overwhelming majority of its people, where no one had to fear old age, or sickness, or being left alone.

Oh yes, he saw the rest, the other. Couldn’t you tell it in his eyes? Didn’t we feel the pain of what he saw, this brother from another planet? At all the funerals of his adopted children, sisters, brothers, mommas, and daddys, in all the jails, at every confrontation with dogs and guns and frightened, narrow, brutal men, he had seen us humans, plumbed the depths of our terror, our cruelty, and our fear, he had seen our selfishness and our blind ambition. But he never stopped looking there.

Always the dream pressed him on, inward, outward, deeper. In the depths of our eyes, roaming even then beyond the walls, he had found the fugitive hope, crouching in corners; he had seen the compassion, gnarled and unused, felt the love, unnamed, unrecognized, unclaimed; he had grasped the oneness, denied and bombed to shreds.

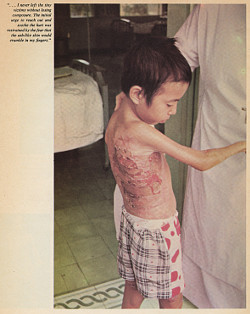

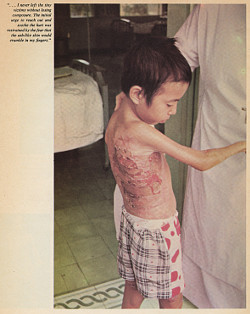

“... I never left the tiny victims without losing composure. The initial urge to reach out and soothe the hurt was restrained by the fear that the ash-like skin would crumble in my fingers.”

Something in this man saw the sister, brother, momma, fearful child in all the strangest places, faces, and he sang to us of what we might become, beyond walls. He sang in the night, sang the old Negro songs, sang the strong black songs, sang the African-sun-soaked songs, and beckoned us, red, white, brown, black, toward ourselves, told us, like Langston—dear brother Langston Hughes—told us, “America is a dream.” And we of every hue and cry, we are the dreamers, creating, dreaming with him, singing with him, dancing with him, to Native American songs, Mexican songs, Scotch-Irish songs, German songs, African songs, Jewish songs, Vietnamese songs, Puerto Rican songs, Appalachian songs.

Organizing, marching, singing the songs, standing unflinching before the blows, going to jail, challenging all the killers of the dreams, he called us to sing, dream, and sing and build—and stand our ground, creating a new reality, a new nation, a new world, ready for the hero. He saw us dancing before we knew we could move. He recognized what we had not seen and was ready to live and die for it, for us.

Early in his movement toward us, back in the 1950s, he was sensing what he saw, saying, “I still believe that standing up for the truth of God is the greatest thing in the world ... come what may.” And for those of us who are getting ready, what truth of God could be greater than the truth of our rich, unexplored human possibilities, our fundamental oneness, our essential union with all life, and our responsibility to live out that truth, politically, economically, socially, spiritually, ecologically, culturally—come what may—against all the systems of separation, dehumanization, and exploitation which deny “what the living may become”?

Are we ready to be what we may become? Oh nation of greatness, do we know who we are, really are, getting ready for our hero, and ourselves?

Long before the bullet struck, Martin was getting ready, moving toward our rendezvous. In the little book of poetry, John Dixon caught a glimpse of the hero becoming, and shared his insight with us:

In an age when courage is measured by destruction, his courage was the courage of love. In an age when men are commodities with a price, he believed in the reality of persons. In an age afraid to believe, his faith was as innocent as a child’s. In an age when subtlety of intelligence serves profit or power, his mind sought the liberations of peace.

What embarrassing words: courage, faith, love, liberation, peace. Haven’t they been outlawed yet? Lock doors, put troops at the gate, guard the legislative halls against courage and faith, against liberation, love, and peace! But here comes the dead man, living, walking, still becoming. He comes piercing our walls, planting courage, planting faith, planting love and peace toward the center of our hearts, reminding us that “intelligence” was not meant to be another word for espionage, spying, and dirty tricks, that doctorates do not have to be sold to the highest bidders, that there is another way, a liberating way, to be shared, as he used to say, “by no D’s and PhD’s.” Are we ready? Is this implacable lover really our hero? Hero of a nation not yet born, but borning? God, are those the pangs we feel?[26]

Coretta Scott King recounts how, on Saturday, April 6, 1968—as Vincent Harding writes, “two days after the bullet of fear and greed, of racism and militarism, and of ignorance and blindness had finally caught up with her husband”—she spoke at Ebenezer Baptist Church in Atlanta about her spouse.

My husband often told the children that if a man had nothing that was worth dying for, then he was not fit to live. He said also that it’s not how long you live, but how well you live. He knew that at any moment his physical life could be cut short, and we faced this possibility squarely and honestly. My husband faced the possibility of death without bitterness or hatred. He knew that this was a sick society, totally infested with racism and violence that questioned his integrity, maligned his motives, and distorted his views, which would ultimately lead to his death. And he struggled with every ounce of his energy to save that society from itself.

He never hated. He never despaired of well doing. And he encouraged us to do likewise, and so he prepared us constantly for the tragedy.

I am surprised and pleased at the success of his teaching, for our children say calmly, ‘Daddy is not dead; he may be physically dead, but his spirit will never die.’

Ours has been a religious home, and this too has made this burden easier to bear. Our concern now is that his work does not die. He gave his life for the poor of the world—the garbage workers of Memphis and the peasants of Vietnam. Nothing hurt him more than that man could attempt no way to solve problems except through violence. He gave his life in search of a more excellent way, a more effective way, a creative rather than a destructive way.

We intend to go on in search of that way, and I hope that you who loved and admired him would join us in fulfilling his dream.

The day that Negro people and others in bondage are truly free, on the day want is abolished, on the day wars are no more, on that day I know my husband will rest in a long-deserved peace.[27]

Trappist Monk Thomas Merton had a gift for seeing the truth of our world with intelligence and coherence. In a letter to a correspondent on New Year’s Eve 1961, Merton wrote about how we had become servants of our own weapons of war:

Our weapons dictate what we are to do. They force us into awful corners. They give us our living, they sustain our economy, they bolster up our politicians, they sell our mass media, in short we live by them. But if they continue to rule us we will also most surely die by them.[28]

“About eight per cent of Vietnam’s population live in refugee shelters or camps; about three quarters of the shelter population, or over 750,000 persons, are children under 16. In shelters like Qui Nhon, pictured here, there is unimaginable squalor and close confinement...”

“Despite the gradual process of animalization, in their striving to maintain a semblance of dignity, they are beautiful.”

The scourge of war that forever changed the world of the children of Vietnam, who physically survived our war in their land, casts an ever-lengthening shadow that haunts us to the present day with ever more effective killing machines including drones and remote-control-engendering-death technologies. The questions before us have not changed since 1967. How have we and how will we respond to the world of hellish death and suffering we fund throughout every year, including on blood money tax day? What are we to do with these lives we have been given to move away from the great levels of materialism that have always been so much a threat to our humanity and the humanity of others? To oppose all war and the machinery of war and come out every day against militarism and against our temptation to live as a new kind of imperial power in the world? To be totally committed to the cause of the poor—in Mississippi, in Chicago, in Appalachia, in Vietnam, in Central America, in South America, in Memphis? To work tirelessly so the cause of the poor becomes the nation’s first priority, until all people are guaranteed jobs or honest income, until our nation stops killing humanity abroad and despoiling the Earth and turns to tend to the desperate needs of its people at home? To dissolve our psychological numbing walls and allow the light of courage, faith, fellowship, love and peace to come into our hearts and thus be reminded that intelligence is not meant to be another word for espionage, spying, and dirty tricks? What truth of God could be greater than the truth of our rich, unexplored human possibilities, our fundamental oneness, our essential union with all life, and our responsibility to live out that truth, politically, economically, socially, spiritually, ecologically, culturally—come what may—against all the systems of separation, dehumanization, and exploitation which deny “what the living may become”?

The questions demanding our response abilities remain. They will not go away. To respond to them may appear to run the gamut from seemingly difficult to impossible. And yet, for our fellow human beings we share this earth with, whose lives have been forever changed by our country’s prosecution of the wars that have ravaged themselves, their loved ones, and their land—and by the demands of capital and its accumulation that has stolen the raw material resources from their land to further pad the Fortunes of the Five Hundred and of the One Thousand—the challenges the poor of the world confront are countably infinite more difficult to respond to than what the majority of we here in the United States face. We have choices and power here that the majority of humanity do not enjoy. The choice and the power resides with us. And the choice to recognize that power, and take responsibility for it, and make this into a world where all of us can live together in peace and fellowship, s i t s r i g h t h e r e.

The comfortable nations often authorize the worst atrocities overseas through fear for their own safety, imagining themselves the victims to be protected from crime at all costs. Such attitudes entitle people in Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen to look in our direction when they ask, “Who are the criminals?” They will be looking at us when they ask that, until we at last exert our historically unprecedented economic and political ability to turn our imperial nations away from ruinous war, and earn our talk of mercy.

—Kathy Kelly, “

The Quality of Mercy,” Voices for Creative Nonviolence, Nov 22, 2017

Afterword

While writing this composition my mind went back to what William Pepper had recounted in 2003: “Then [MLK] asked to meet with me and asked me to open my files to him that went well beyond what was published in the Ramparts piece in terms of photographs.” I wrote Mr. Pepper asking if he would be amenable to my including some of the additional photographs he described sharing with Martin King in addition to those published in Ramparts. Apologizing for not being able to fulfill my request, he responded with the following:

Many years ago, when I lived on Roosevelt Island, in one of a number of break-ins to my apartment by the local FBI, my photo files were raided and stolen. The thefts included my surveillance photos of Raul as well as the Vietnam files. Strangely, they left the autopsy photos of MLK – perhaps to be a reminder.

The power of truth force contained in such a photographic record was validated by its theft at the hands of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Whose interests are served by such breaking and entering thievery? Who directs and orders the confiscation by federal police of our collective history? What are the true costs to this society—and by extension to all of humanity—of having its factual historical record gagged, buried, classified, omitted, distorted, and stolen? And whose interests are served by such malevolent hatred, theft, and destruction of historical truth?

Appendix B in William Pepper’s 2016 book, The Plot To Kill King,[29] is titled “Ramparts Magazine—The Children of Vietnam” and includes a black-and-white reproduction of his January 1967 work. The introduction to it states:

As human beings, we sometimes are confronted with experiences which render us substantively different individuals than we were prior to exposures. Vietnam had this effect upon me. It was soul shattering—first, because of what was done to those innocents, and secondly because we, the American people and our tax dollars, caused it under the self-serving lies and greed which underlay the atrocities. Virtually every war crime imaginable was committed against this ancient people and their children.

These victims are embedded in my being. Dr. King wept when he was confronted with the images, but the history and its narrative, which moved him to oppose the war in 1967, should be remembered, and is without doubt, a part of his legacy.[30]

Near the beginning of his Riverside Church Address, Dr. King said,

I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice. I join you in this meeting because I am in deepest agreement with the aims and work of the organization which has brought us together, Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam. The recent statements of your executive committee are the sentiments of my own heart, and I found myself in full accord when I read its opening lines: “A time comes when silence is betrayal.”

As members of our single human family, one of many responsibilities is to bear witness to actions and situations that run counter to our best instincts and understanding and to use our intelligence and empathy to always shift direction towards nurturing and caring for others and for our single, indivisible planetary home. Throughout his life William Francis Pepper has been a tireless champion of humanity and a messenger of truth. His distinct persona, in evidence throughout his decades of writing as well as his actions and deeds, expresses great empathy and concern for the innocents who suffered grievous trauma as a result of the self-serving lies and greed that has driven and promoted United States “national security interests” over and above the interests of Life on Earth. This writer is deeply grateful for William Pepper’s undying love for his fellow woman and man, children and elders, and Life unbounded on Earth, now and especially for those yet unborn who can not speak up on their own behalf and for their world yet to be.

William Pepper’s witness in The Children of Vietnam connects many historical threads contained in the tapestry of our epoch. Two primary elements are what President Kennedy and Martin King gave of themselves to change the course of the human project in a more excellent way, a more effective and creative way. For both humans, they were willing to pay the supreme price to pursue the visions they expressed of helping move towards a peaceful and just world. In an illuminated 1998 essay titled, “The Assassinations of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy in the Light of the Fourth Gospel,”[31] Jim Douglass explores how “Kennedy, like King, lived the word agape: ‘No one has greater love than that this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends’ (John 15:13).”[32]

The stories by which we can understand Martin Luther King and John Kennedy are biblical. Martin Luther King, like John the Baptist in the Fourth Gospel, came as a witness to testify to the light of agape coming into our world—the light of truth and nonviolence which enlightens everyone. He testified to agape made flesh in justice for the oppressed and love for the enemy. He testified to the possibility of agape made flesh in a new America.

In his final, most radical presidential address to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, King dealt with the question of restructuring the whole of American society. He asked, “Why are there forty million poor people in America?” “When you ask that question,” he said, “you begin to question the capitalistic economy.” In order to “help the discouraged beggars in life’s marketplace,” King said, “one day we must come to see that an edifice which produces beggars needs restructuring.”...[33]

John F. Kennedy was raised from the death of wealth, power, and privilege. The son of a millionaire ambassador, he was born, raised, and educated to rule the system. When he was elected President, Kennedy’s heritage of power corresponded to his position as head of the greatest national security state in history. But Kennedy, like Lazarus, was raised from the death of that system. In spite of all odds, he became a peacemaker and, thus, a traitor to the system....[34]

It was a miracle that a man of John F. Kennedy’s background should be born again as a peacemaker. The Fourth Gospel’s final words on Lazarus are: “So the chief priests planned to put Lazarus to death as well, since it was on account of him that many of the Judeans were deserting and were believing in Jesus” (John 12:10-11, my emendations). The great danger John Kennedy posed to the system was that many Americans, even people of power, would on account of him desert a cold war vision and believe in peace.

In his address before the 18th General Assembly of the United Nations, September 20, 1963, John Kennedy said:

Two years ago I told this body that the United States had proposed, and was willing to sign, a limited test-ban treaty. Today that treaty has been signed. It will not put an end to war. It will not remove basic conflicts. It will not secure freedom for all. But it can be a lever; and Archimedes, in explaining the principles of the lever, was said to have declared to his friends: “Give me a place where I can stand—and I shall move the world.”

My fellow inhabitants of this planet: Let us take our stand here in this assembly of nations. And let us see if we, in our own time, can move the world to a just and lasting peace.[35]

The place where John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King stood so as to move the world was in the presence of all nations, before their God, ready to lay down their lives for a just and lasting peace.

No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.[36]

Each of us has tremendous gifts and the energy sparked by the upwelling needs of Life to carry on the work of those who came before us. Resurrecting the JFK and the MLK within sets before us the task of exploring ways of implementing the imperative of peacemaking each of them gave their lives for. Exercising our intelligence in this manner, with clarity and coherence, is of the highest calling Life presents us with. Continuing the work of those who devoted their lives to be peacemakers is before every one. No one can ever take that away from us.

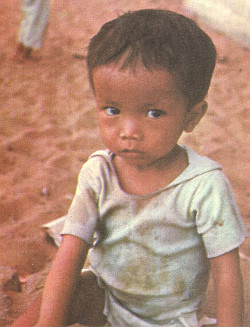

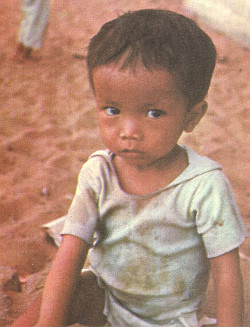

“One tiny child provided for me their symbol. He was about three years old and he sat on the ground away front the others. He was in that position when I entered and still there several hours later when I left. When I approached he nervously fingered the sand and looked away, only to finally confront me as I knelt in front of him. Soon, I left and he remained as before—alone.”

References

[

↩]

Good introductions to this subject include:

Alfred McCoy,

In the Shadows of the American Century: The Rise and Decline of U.S. Global Power (2017)

William Blum:

Killing Hope: U.S. Military and CIA Interventions Since World War II (2004)

Rogue State: A Guide to the World’s Only Superpower (2005).

America’s Deadliest Export: Democracy - The Truth About U.S. Foreign Policy and Everything Else (2013)

Michael Parenti,

The Face of Imperialism (2011)

Peter Dale Scott,

Drugs, Oil, And War (2003)

F. William Engdahl,

A Century of War: Anglo-American Oil Politics and the New World Order (2004)

[

↩] William F. Pepper, “

The Children of Vietnam,”

Ramparts,

January 1967, pp. 45-68.

[

↩]

From David Swanson, “

PBS’s Vietnam Acknowledges Nixon’s Treason,”

Let’s Try Democracy, October 11, 2017:

I want to call particular, and grateful, attention to one item that the PBS film does include, namely Richard Nixon’s treason. Five years ago, this story showed up in an article by

Ken Hughes, and others by

Robert Parry. Four years ago it made it into

The Smithsonian, among other places. Three years ago it gained notice in a corporate-media-approved book by

Ken Hughes. At that time,

George Will mentioned Nixon’s treason in passing in the Washington Post, quite as if everyone knew all about it. In the new PBS documentary, Burns and Novick actually come out and state clearly what happened, in a manner that Will did not. As a result, a great many more people may indeed actually hear what happened. What happened was this. President Johnson’s staff engaged in peace negotiations with the North Vietnamese. Presidential candidate Richard Nixon secretly told the North Vietnamese that they would get a better deal if they waited. [UPDATE: He sent a similar message to the South Vietnamese that also helped sabotage the talks.] Johnson learned of this and privately called it treason but publicly said nothing. Nixon campaigned promising that he could end the war. But, unlike Reagan who later sabotaged negotiations to free hostages from Iran, Nixon didn’t actually deliver what he had secretly delayed. Instead, as a president elected on the basis of fraud, he continued and escalated the war (just as Johnson had before him). He once again campaigned on the promise to finally end the war when he sought re-election four years later—the public still having no idea that the war might have been ended at the negotiating table before Nixon had ever moved into the White House if only Nixon hadn’t illegally interfered (or might have been ended at any point since its beginning simply by ending it).

[

↩]

James Galbraith: Kennedy was pulling out of Vietnam, Nightly News with Vincent Browne, TV3 Ireland, 2009

See Also: from James K. Galbraith:

“

Exit Strategy - In 1963, JFK ordered a complete withdrawal from Vietnam,” Boston Review, October/November 2003

“

JFK’s Plans to Withdraw, New York Review of Books, December 6, 2007.

“

JFK’s Vietnam Withdrawal Plan Is a Fact, Not Speculation, The Nation, November 22, 2013.

“

JFK Had Ordered Full Withdrawal from Vietnam: Solid Evidence – PBS Vietnam Series: Glossing over JFK’s Exit Strategy,” Who.What.Why, September 26, 2017.

[

↩]

Published in

Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961-1963, Volume IV: August-December 1963 (Washington, U.S. Government Printing Office, 1991), Document 194.

National Security Action Memorandum No. 263, October 11, 1963, pp.

395-

396. Source: Department of State, S/S-NSC Files: Lot 72 D 316, NSAMs. Top Secret; Eyes Only. The Director of Central Intelligence and the Administrator of AID also received copies. Also printed in United States-Vietnam Relations, 1945-1967, Book 12, p. 578.

NSAM #263 though very brief, initiated what President Kennedy had begun to implement for withdrawing U.S. military forces from Vietnam. Although short, this memorandum directly refers to and builds from the Taylor/McNamara Report (Document 167) as well as Documents 179 and 181.

Document 167.

Memorandum From the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (Taylor) and the Secretary of Defense (McNamara) to the President, October 2, 1963, pp.

336-

346. Source: Kennedy Library, National Security Files, Vietnam Country Series, Memos and Miscellaneous. Top Secret.

Audio recording:

NSC Meeting on McNamara-Taylor Report on Vietnam, 2 October 1963 (28:45), Tape 114/A49, jfklibrary.org.

Document 179.

Memorandum for the Files of a Conference With the President, October 5, 1963, pp.

368-

370. Source: Kennedy Library, National Security Files, Vietnam Country Series, Memos and Miscellaneous. Top Secret.

Document 181.

Telegram From the Department of State to the Embassy in Vietnam, October 5, 1963, pp.

371-

379. Source: Source: Department of State, Central Files, POL 15 S VIET. Top Secret; Immediate Prepared by Hilsman with clearances of Harriman and Bundy. Cleared in draft with Rusk and McNamara. Regarding the drafting of this cable, see

Document 179. Repeated to CINCPAC for POLAD exclusive for Felt.

[

↩]

Kenneth P. O’Donnell and Dave F. Powers with Joe McCarthy,

Johnny, We Hardly Knew Ye; Memories of John Fitzgerald Kennedy (Boston: Little Brown, 1970), p. 17.

[

↩]

Full transcript:

Jim Douglass on The Hope in Confronting the Unspeakable in the Assassination of President John Fitzgerald Kennedy, Keynote Address at The Coalition on Political Assassinations Conference, 20 November 2009, Dallas, Texas.

[

↩]

See

Selected Writings of John Judge, ratical.org.

[

↩]

Kenn Thomas from the Foreword,

Judge for Yourself: A Treasury of Writing by John Judge (

Say Something Real Press, 2017), p. vi.

[

↩]

Transcript of film:

John Judge: September 11 Critical Analysis, Kane Hall, University of Washington, Seattle, 16 February 2002.

[

↩]

Transcript:

William F. Pepper: An Act of State – The Execution of Martin Luther King, Talk at Modern Times Bookstore, San Francisco, 4 February 2003.

[

↩]

Wayne Morse remarks before the Senate of the United States, August 22, 1966, appears in “

The Children of Vietnam.”

[

↩]

Jim Douglass,

A Letter to the American People (and Myself in Particular) On the Unspeakable; first published in

Fair Play Magazine, 1999, extended on ratical.org, 2012.

[

↩]

Bernard Lee quoted in David Garrow,

Bearing the Cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (New York: Vintage Books Classics, 1988), p. 543.

[

↩]

Transcript: 2003 Pepper Talk.

[

↩]

For an account of his final year see: Ratcliffe, “

50 Years Ago: Riverside Church and MLK’s Final Year of Experiments With Truth,” rat haus reality press, April 4, 2017.

[

↩]

Vincent Salandria, Chapter 18.

Notes on Lunch with Arlen Specter,

False Mystery - Essays on the JFK Assassination (rat haus reality press: Boston, 2017).

[

↩]

Transcript: Jim Douglass,

Conclusion, COPA 2009

Keynote Address.

[

↩]

Today United States military and covert operations are carried out from

more than 1,000 foreign U.S. military bases that surround the world. In “

The Children of Vietnam,” William Pepper wrote how, “When we hear about these burned children at all, they’re simply called ‘civilians,’ and there’s no real way to tell how many of them are killed and injured every day.” The following partial list contains contemporary reports of devastating consequences to civilian populations engendered by U.S. warlords and military contractors. The military-industrial-intelligence-congressional complex learned the lesson of Vietnam—where on-the-ground footage of the human toll of the war was broadcast nightly on television news—and ceased producing nor allowing detailed reports about the numbers of people killed or injured by U.S. forces. This past July, Kathy Kelly wrote about “

What Does War Generate?”:

At an

April, 2017 Symposium on Peace in Nashville, TN,

Martha Hennessy spoke about central tenets of

Maryhouse, a home of hospitality in New York City, where Martha often lives and works. Every day, the community there tries to abide by the counsels of

Dorothy Day, Martha’s grandmother, who co-founded houses of hospitality and a vibrant movement in the 1930s. During her talk, she held up a postcard-sized copy of one of the movement’s defining images, Rita Corbin’s celebrated woodcut listing “The Works of Mercy” and “The Works of War.”

She read to us. “The Works of Mercy: Feed the hungry; Give drink to the thirsty; Clothe the naked; Visit the imprisoned; Care for the sick; Bury the dead.” And then she read: “The Works of War: Destroy crops and land; Seize food supplies; Destroy homes; Scatter families; Contaminate water; Imprison dissenters; Inflict wounds, burns; Kill the living.” The following week, General James Mattis was asked to estimate the death toll from the U.S. first use in Nangarhar province, Afghanistan, of the MOAB, or

Massive Ordinance Air Burst bomb, the largest non-nuclear weapon in U.S. arsenals. “We stay away from BDA, (bomb damage assessment), in terms of the number of enemy killed,” he told reporters traveling with him in Israel. “It is continuing our same philosophy that we don’t get into that, plus, frankly,

digging into tunnels to count dead bodies is probably not a good use of our troops’ time.” His comment seemed to echo another General,

Colin Powell, who, when asked how many Iraqi soldiers might have been killed by U.S. troops invading Iraq in 1991, commented, “That’s not really a number I’m terribly interested in.” Other generals noted that some of those Iraqi troops, conscripts trying to surrender, were literally buried alive in their trenches by plow attachments affixed to U.S. tanks. More recently, Lieutenant General

Aundre F. Piggee acknowledged that during the 2007 U.S. military surge in Iraq, when civilian casualties rose by 70%, the U.S. military wasn’t “necessarily concerned” about limiting civilian deaths.

One measure of how much suffering and death is caused every day by the United States abroad can be gleaned from the enumeration of U.S. base deployments given that stationed military and clandestine forces personnel can be counted on to be actively engaged in their geographical spheres of operations. As well, independent reporting by witnesses and writers who cover the ongoing nightmare of U.S. military aggressions and intelligence agency covert operations fills in more of the tapestry of carnage and bloodshed perpetrated upon those unfortunate enough to find themselves in the crosshairs of U.S. national security interests.

The current U.S.-generated suffering and violence in Iraq stretches over 26 years:

Bert Sacks, “

Don’t forget the harm done to children during the Gulf War,” Real Change, Oct 11, 2017

“

On destroying civilian infrastructure during the Gulf War and consequences for the civilian population,” from

Interfaith Network of Concern for the People of Iraq & Citizens Concerned for the People of Iraq

Bert Sacks:

Fined for Helping Iraqi Kids

Kathy Kelly:

“

The Quality of Mercy,” Voices for Creative Nonviolence, Nov 22, 2017

The comfortable nations often authorize the worst atrocities overseas through fear for their own safety, imagining themselves the victims to be protected from crime at all costs. Such attitudes entitle people in Iraq, Afghanistan and Yemen to look in our direction when they ask, “Who are the criminals?” They will be looking at us when they ask that, until we at last exert our historically unprecedented economic and political ability to turn our imperial nations away from ruinous war, and earn our talk of mercy.

“

How Afghans View the Endless US War,” Consortiumnews.com, Nov 2, 2017

“

What Does War Generate?,” Voices for Creative Nonviolence, Jul 3, 2017

Jason Ditz:

“

Pentagon Admits to Only Tiny Fraction of Civilians Killed in Iraq and Syria,” AntiWar.com, Nov 30, 2017

“

Pentagon to Use Armed Drones in Niger First Flights Expected Within Days ,” AntiWar.com, Nov 30, 2017

“

Pentagon Wants to Keep Report on Afghan Child Sex Abuse Classified,” AntiWar.com, Nov 26, 2017

“

US Looks to Dramatically Escalate Involvement in Libya - Permanent US Military Presence Considered,” AntiWar.com, Jul 10, 2017

Jessica Corbett:

“

Millions on Brink of Death in Yemen, But Members of Congress Can't Be Bothered With Questions,” Common Dreams, Nov 10, 2017

Moon of Alabama:

“

Yemen — Having Lost the War Saudis Try Genocide — Media Complicit, Global Research / Moon of Alabama, Nov 13 2017

Bill Van Auken:

“

Crimes against Humanity: US-backed Saudi Blockade Deprives 2.5 Million Yemenis of Clean Water, Global Research / World Socialist Web Site, Nov 22 2017

Eddie Haywood:

“

US Expands Military Offensive in Somalia,” Global Research / World Socialist Web Site, Nov 24 2017

Abayomi Azikiwe:

“

Pentagon Escalates Military Presence in Yemen: Genocidal Cholera Epidemic, U.S. Seeks to Seize Control of Yemen’s Strategic Resources,” Global Research, Aug 8, 2017

“

Trump Administration Signals Escalation of War in Somalia,” Global Research, Apr 11, 2017

Nicolas J S Davies:

“

America’s Renegade Warfare,” Consortiumnews.com, Nov 16, 2017

“

Playing Games with War Deaths,” Consortiumnews.com, Jan 17, 2016

Alex Ward:

“

The US-led War Against ISIS Is Killing 31 Times More Civilians Than Claimed. Report,” Global Research / Vox, Nov 19/16 2017

Nick Turse:

“

America’s War-Fighting Footprint in Africa - Secret U.S. Military Documents Reveal a Constellation of American Military Bases Across That Continent,” TomDispatch.com, Apr 27 2017

Rebecca Gordon:

“

It’s 2016. Do You Know Where Your Bombs Are Falling? The Forgotten War in Yemen and the Unchecked War Powers of the Presidency in the Age of Trump,” TomDispatch.com, Dec 11, 2016

“

The Secret to Winning the Nobel Peace Prize - Keep the U.S. Military Out,” TomDispatch.com, Oct 20, 2015

Bureau of Investigative Journalism:

Reports:

Somalia: Reported US covert actions 2001-2016

Afghanistan: Reported US covert actions 2017

Pakistan: Reported US strikes 2017

Somalia: Reported US actions 2017

Yemen: Reported US covert actions 2017

Drone Warfare

Drone Wars: The Full Data

Drone Strikes in Afghanistan

Drone Strikes in Pakistan

Drone Strikes in Somalia

Drone Strikes in Yemen

Stephen Lendman:

“

America’s Drone Command Centers: Remote Warriors Operate Computer Keyboards and Joysticks,” Global Research, Apr 29, 2012

James A Lucas:

“US Has Killed More Than 20 Million People in 37 ‘Victim Nations’ Since World War II,”

Global Research /

CounterCurrents.org, Nov 9, 2017 / Apr 24, 2007

John Horgan:

“

Where Is Outcry Over Children Killed by U.S.-Led Forces? Scientific American, Sep 10, 2015

[

↩]

Neta C. Crawford (Boston University),

US Budgetary Costs of Post-9/11 Wars Through FY2018: $5.6 Trillion,

COSTS OF WAR, Watson Institute International & Public Affairs, Brown University, November 2017.

Summary Article: Costs of War: “

U.S. spending on post-9/11 wars to reach $5.6 trillion by 2018,” Brown University, RI, November 7, 2017.

[

↩]

Vincent Harding,

Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero, (Maryknoll, NY:

Orbis Books, 2008)

[

↩]

Film:

Vincent Harding - The Inconvenient Hero, Martin Luther King (8:26), Ikeda Center, November 11, 2010. The complete transcript of the recording:

Dr. Harding, why do you call Martin Luther King the inconvenient hero? Mm-hmm. The first thing that I should say is that I feel very comfortable in naming him since he was my friend. Ever since we began talking about establishing a national holiday honoring King in this country it’s been very clear to me that there has been a great tension. Many of those, who, out of the best intention wanted to see the country honor Martin, many of them knew, at least they felt they knew, that the country could not take Martin as he was. That somehow Martin would have to be somewhat domesticated in order for the country to deal with him. Because he was both a prophet, seeking to speak the truth to the country, and a lover, seeking to grasp the country in his great affection for the country. And it’s very hard, as you know, for us to take both of those energies at once. There’s always a temptation to want to ask the the prophet to back off some and not to be so demanding on us and not to keep calling us to our best possibilities. That was what King was about. Calling us from our more easy, convenient stances in our old and not helpful ways, he was calling us beyond that. Always calling us to go outside of that. Calling us to give up, for instance, on the whole experience and teaching and living of white supremacy. Calling us to move away from the great levels of materialism that have always been so much a threat to our humanity and the humanity of others. And he was always calling us to look at the world, not through the eyes of a dominator, but through the eyes of sisters and brothers to the world. Those calls were hard for people to take. On the other hand people knew that there was something right about honoring King as our hero. What essentially happened is that those who were responsible both at national levels and local levels for developing the traditions of honoring King, chose the most convenient ways, the least challenging ways. So for instance, instead of taking the 1963 speech, with its presentation of the ways in which black people had been treated so unjustly and his cataloguing of that injustice, they took the piece of the speech at the very end in which he was essentially saying that as long as we continue to struggle for a better country, then he has a dream that this can come. But we took that last piece—“I have a dream.” Not talking anymore about the injustices. Not talking about the struggle that is necessary to overcome the injustices. Going as quickly as possible to the dream of the country with justice. All through our treatment of King we forgot the pieces that were most difficult for us to handle. Almost never, in most of the celebrations, is there any lifting up of his powerful statement against the war and against the machinery of war and against militarism and against our temptation to live as a new kind of imperial power in the world. We took him, we wrapped him in the most, in most cases, in the most unchallenging attire; made him convenient to where we wanted to be; made him convenient to our unchallenged pathways. So I have to call him an inconvenient hero because I am convinced that the ways in which, by and large, he has been dressed, attired, by the desire to create this national holiday, in order to get the holiday, in order to keep the holiday, in order to make the holiday acceptable to all kinds of people, we have diminished him and we have made him fit our convenience. I’m quite convinced that he can never become all that he needs to become for us unless we are willing to open ourselves to the prophetic pastor, to the crier out for justice and rightness and open ourselves to what would have to be called the very tough love that he wanted to share with us. Otherwise he’ll be a hero who has nothing to offer us except a dim reflection of ourselves and we don’t need any more of that.

[

↩]

Harding, The Inconvenient Hero, p. 28.

Concerning the Poor People’s Campaign and mobilization that was being planned by Martin Luther King to commence in the spring of 1968 in the nation’s capital, his commitment was to bring 500,000 people to Washington culminating in an encampment in the shadow of the Washington Memorial, to force the United States government to abolish poverty (see An Act of State, p. 7). In a lecture transmitted over the Canadian Broadcast Corporation radio network in late 1967, Martin King expressed his vision first of a national and then a global nonviolent revolution against the increasing concentration of financial wealth in the U.S. corporate empire state and its encompassing military power.

Nonviolent protest must now mature to a new level to correspond to heightened black impatience and stiffened white resistance. This higher level is mass civil disobedience. There must be more than a statement to the larger society; there must be a force that interrupts its functioning at some key point. That interruption must not, however, be clandestine or surreptitious. It is not necessary to invest it with guerrilla romanticism. It must be open and, above all, conducted by large masses without violence. If the jails are filled to thwart it, its meaning will become even clearer.... Mass civil disobedience as a new stage of struggle can transmute the deep rage of the ghetto into a constructive and creative force. To dislocate the functioning of a city without destroying it can be more effective than a riot because it can be longer-lasting, costly to the larger society, but not wantonly destructive. Finally, it is a device of social action that is more difficult for the government to quell by superior force. (Lecture reprinted as Chapter 1, Impasse In Race Relations, in Martin Luther King,

The Trumpet of Conscience (Boston: Beacon Press, 2010) pp. 15-16.)

Dr. King wasn’t just talking about “dislocat[ing] the functioning of a city without destroying it.” He and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference were preparing a very real plan

announced on December 4, 1967 for a Poor People’s Campaign to commence on-the-ground in Washington D.C. in the spring of 1968:

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference will lead waves of the nation’s poor and disinherited to Washington, D.C. next spring to demand redress of their grievances by the United States government and to secure at least jobs or income for all. We will go there, we will demand to be heard, and we will stay until America responds. If this means forcible repression of our movement we will confront it, for we have done this before. If this means scorn or ridicule we embrace it, for that is what America’s poor now receive. If it means jail we accept it willingly, for the millions of poor already are imprisoned by exploitation and discrimination. But we hope with growing confidence that our campaign in Washington will receive at first a sympathetic understanding across our nation followed by dramatic expansion of nonviolent demonstrations in Washington and simultaneous protests elsewhere. In short, we will be petitioning our government for specific reforms and we intend to build militant nonviolent actions until that government moves against poverty.

A measure of what the assassination of Martin Luther King resulted in was that at its peak, the 7,000 protestors who lived in Resurrection City between mid-April and June 19, 1968, was less than two percent of the half-million people Martin King was committed to bringing to Washington D.C. while he was still alive.

[

↩]

Ibid. p. 41.

[

↩]

Ibid. pp. 31-32.

[

↩]

Ibid. pp. 34-36.

[

↩]

Coretta Scott King,

My Life With Martin Luther King, Jr., Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1969,

p. 327.

[

↩]

Thomas Merton,

Cold War Letters, (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 2006), p. 43.

[

↩]

Dr. William F. Pepper Esq,

The Plot To Kill King: The Truth Behind the Assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. (NY:

Skyhorse Publishing, 2016)

[

↩]

Ibid. p. 344.

[

↩]

Jim Douglass, “

The Assassinations of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy in the Light of the Fourth Gospel,” Sewanee Theological Review 42:1 (1998), The School of Theology, University of the South, Sewanee, Tennessee, pp. 26-46.

[

↩]

Ibid. p. 40

[

↩]

Ibid. p. 45. “Why are there forty million poor people...” from Martin Luther King, “

Where Do We Go From Here?,” Delivered at the 11th Annual SCLC Convention Atlanta, GA, Aug 16, 1967.

[

↩]

The Assassinations of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy, p. 42.

[

↩]

Transcript, audio of

Address before the 18th General Assembly of the United Nations, Sep 20, 1963.

[

↩]

The Assassinations of Martin Luther King and John F. Kennedy, p. 46.

Copyright © 1996, 2008 by Vincent Harding.

Excerpts from Martin Luther King: The Inconvenient Hero reproduced with the permission of Orbis Books

Original at Ratical.org https://ratical.org/ratville/JFK/CoV-JFK-MLK-WFP.html