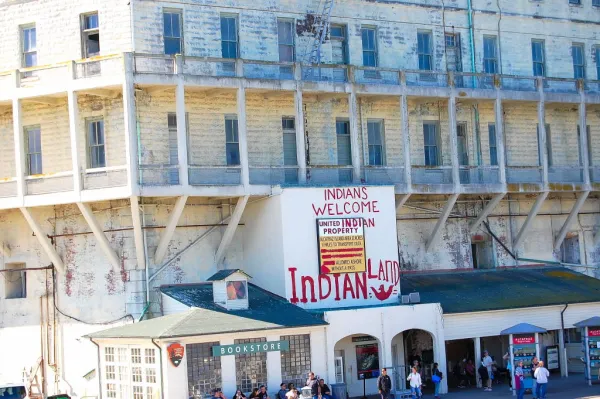

Photo Credit: Ed Rampell PitcairnAlcatrazModel = The model of Alcatraz at San Francisco Harbor's Pier 33, where you get the ferry to The Rock. PitcairnAlcatrazSanFran1 = A view of San Francisco from the ferry to Alcatraz. PitcairnAlcatrazGoldenGate = The ferry to Alcatraz offers spectacular views of San Francisco Bay, including of the Golden Gate Bridge. PitcairnAlcatraz = The ferry nears Alcatraz. PitcairnAlcatraz = More than any other isle on Earth Alcatraz epitomizes the island as a symbol of imprisonment. PitcairnAlcatrazIndian = As soon as ferry passengers arrive at Alcatraz they are greeted by "graffiti" from the 1969 American Indian occupation. PitcairnAlcatrazRanger Benny = Ranger Benny gives his talk about Alcatraz's political prisoners. PitcairnAlcatrazWaterTowerIndian = The water tower at Alcatraz is also scrawled with graffiti from the Indian occupation. PitcairnJohnsGrill = The restaurant John's Grill is a historic landmark, as well as a great place to dine. PitcairnJohnsGrilHammett = Mira Larkin, granddaughter of a Hollywood Ten screenwriter, admires John's Grill's shrine to another writer who became a political prisoner, Dashiell Hammett.

Separated by water from continents, islands have always represented freedom to me. When I graduated from Hunter College as a film major in the 1970s, I realized the Age of Aquarius was experiencing technical difficulties in ascending. So, inspired by movies like Mutiny on the Bounty, I decided to go search for paradise in the South Pacific, going on to visit and live at more than 100 islands in Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia.

Before my latest journey, only three islands remained on my bucket list. At the head of the list was the apogee of isles symbolizing liberty: Pitcairn Island, where the Bounty mutineers and their Tahitian lovers fled to escape capture and punishment by the British navy after seizing the Bounty and throwing Captain Bligh overboard in 1789.

For others, however, islands exemplify the idea of imprisonment. In 1814, Napoleon Bonaparte was confined at Elba in the Mediterranean, 6 miles off Italy’s coast. After the French Emperor returned to France and his army was defeated at Waterloo, the British took no chances and exiled Napoleon to remote St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean, 1,200 miles from southwestern Africa.

In 1852, Devil’s Island was opened 9 miles from French Guiana and served as a penal colony for a century. Devil’s Island’s most famous inmates included the wrongfully accused Captain Alfred Dreyfus and Henri Charrière, aka “Papillon.” Before winning the Nobel Peace Prize and becoming South Africa’s president, Nelson Mandela was held at the maximum security prison on Robben Island, about 4 miles from Cape Town.

However, the most iconic prison island in the world is Alcatraz. So, it seemed fitting for me to start my expedition to Pitcairn, that emblem of escaping to freedom, at the epitome of the isle as incarceration in San Francisco Bay – and to cover in this series the islands and atolls I encountered in between these polar opposites.

Jailhouse Rock: Political Prisoners

As my United Airlines flight to Tahiti – where I’ll board the cargo-cruiser Aranui 5 for my voyage to Pitcairn – is via San Francisco, I fly there from L.A. and spend my first night at the centrally-located Hilton San Francisco Union Square in a spacious room with a balcony offering a spectacular, sparkling vista of the City by the Bay. The next day I ride a taxi from downtown to Pier 33, where solar/wind-powered ferries transport about 5,000 visitors a day to “The Rock.” From afar, Coit Tower overlooks the pier, a sort of outdoors museum featuring a large model of Alcatraz, placards bearing text about and photos of the historic hoosegow and its infamous inhabitants, plus a full-size replica of a Rodman cannon, the type of artillery deployed there during the Civil War, when the lonely outpost was a fort.

The 15-minute or-so ferry ride unfolds the splendor of San Francisco Bay, from Frisco’s cityscape to Golden Gate Bridge to the west. The landing at the islet, too, features dramatic memories of days gone by: On a five-story building, beside what’s now a bookstore, oversized graffiti in red paint announces, in part, “INDIANS WELCOME… INDIAN LAND.” These and other slogans punctuate the abandoned prison on its water tower and beyond, graphic artifacts scrawled by Indigenous protesters during the American Indian Movement’s 1969 occupation that demanded repatriation of federally-owned land no longer used by the U.S. government to Native people.

Sioux poet John Trudell served as spokesman for AIM takeover of Alcatraz, which was visited by celebrities of conscience and consciousness, such as activist actors Jane Fonda and Marlon Brando, comic Dick Gregory and singer Buffy Sainte-Marie, herself of the Piapot Cree Nation and the first Indigenous talent to win an Oscar, for the song “Up Where We Belong” from the 1982 movie An Officer and a Gentleman.

The “Red Power” direct action and the fact that signposts of it remain is highly appropriate, considering the fact that according to Ranger Benny Batom, in 1895 Hopi “hostiles” were among Alcatraz’s early captives. And what was the heinous “crime” these “redskins” had perpetrated that rated their getting shipped out from Arizona all the way to San Francisco Bay to do time? The Hopis were incarcerated for refusing to send children to Indian boarding schools.

I’m in luck because immediately after I arrive at the visitor destination that’s now managed by the National Park Service, Ranger Benny begins his eye-opening Howard Zinn-like tour that could be entitled “A People’s History of Alcatraz.” Although The Rock is primarily known for imprisoning a who’s who of America’s most wanted, Ranger Benny, the site’s longtime Education Program Manager, points out that it was a federal penitentiary for only 29 years. The U.S. Army and Navy’s presence on Alcatraz began in the 1850s; military prisoners were held in the 1857-constructed Guardhouse, the isle’s oldest building still standing, including disorderly soldiers and, during the Civil War. captured Confederates.

In addition to the aforementioned recalcitrant Hopi tribesmen, Ranger Benny reveals a rather sordid tale of other political prisoners, also often minorities, largely obscured by the mist time, who were incarcerated at the frequently fog-shrouded islet for the “crime” of dissent after the passage of the Espionage Act. “In 1918 Robert Simmons was a Black soldier who was court-martialed in France” for disobeying orders during World War I, relates Ranger Benny, who is also African American. Simmons was one of 30 Conscientious Objectors imprisoned in inhumane, dungeon-like conditions at Alcatraz for being against WWI (see: https://www.nps.gov/articles/robertsimmonsprisonerconsciencealcatraz.htm).

Another forgotten C.O. was the Jewish anarchist Philip Grosser, who Ranger Benny tells us was thrown behind bars for agitating that “War is no place for a workingman.” The last antiwar inmate to be released from Alcatraz, Grosser – who was reportedly held in solitary confinement and a “coffin cage” – wrote an early exposé, a 32-page pamphlet entitled Uncle Sam’s Devil’s Island.

John’s Grill and Hollywood’s Outcasts

Surprisingly, Alcatraz didn’t become a federal pen, where 1,500 of America’s most notorious criminals served hard time, until 1934 – but more on that later. Sticking with the theme of political prisoners, the night before I went to jail, San Francisco resident Mira Larkin meets me in the lobby of the Hilton San Francisco Union Square and we stroll to the nearby John’s Grill to dine. Mira’s grandfather, Academy Award winning screenwriter Albert Maltz, who’d joined the Communist Party USA during the Depression, became one of America’s most famous political prisoners.

In 1942 Maltz wrote one of the early film noirs, the action-packed, vengeance-filled This Gun for Hire, starring Alan Ladd and Veronica Lake (see: https://www.imdb.com/title/tt0035432/?ref_=nm_flmg_t_31_wr). He also wrote the gung-ho World War II morale boosters 1943’s Destination Tokyo and 1945’s Pride of the Marines. Maltz co-won an Oscar for writing the short The House I Live In, with Frank Sinatra singing the title song, extolling America as a land of tolerance in 1946.

The following year, Mira’s grandfather was “thanked” for his patriotic scripts by being subpoenaed to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Insisting on his First Amendment right to free speech, Maltz was blacklisted along with the rest of the Hollywood Ten for refusing to inform on other suspected “subversives” and to answer invasive questions like: “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” In addition to being banned from working in the motion picture industry, the Hollywood Ten were all cited for contempt of Congress, fined and sentenced to up to one year in prison (Maltz went to Mill Point Federal Prison in West Virginia; none of the Ten did time at Alcatraz).

Homage to Hammett

At John’s Grill Mira and I enjoy creamy New England clam chowder with a soft constituency. We dine on generous portions of tasty halibut and lamb chops with broccoli and carrots, served by attentive waiters. The storied eatery bills itself as “the downtown gathering place for those who ran the town and those who wanted to run the town,” and one of its many notable patrons was novelist Dashiell Hammett, whose private eye Sam Spade dined at John’s Grill.

The author is honored in an upstairs shrine. Behind glass in a large display case are signed copies of Hammett’s detective books such as The Thin Man, as well as a replica of the eponymous The Maltese Falcon, the supposedly priceless statuette of the bird of prey in Hammett’s 1930 novel and the 1941 John Huston-directed movie nominated for three Oscars, including Best Picture, starring Humphrey Bogart. The faux falcon is perched beside an Emmy Award, while an image of the famed bird is emblazoned on the logo of John’s Grill’s which, in addition to being a fine dining establishment is a National Literary Landmark, home of “The Maltese Falcon Room.” For literary and Film Noir aficionados, this author’s altar is, in Sam Spade’s words, “The stuff that dreams are made of.”

Hammett, who had joined the CPUSA, not only wrote hardboiled fiction, but when he was summoned to testify before a District Court in 1951 refused to break under pressure and (like Maltz) become an informer. Convicted of contempt of court he was sentenced to six months, served mostly at the Federal Correctional Institution near Ashland, Kentucky. Hammett subsequently appeared before Sen. Joe McCarthy’s Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations on March 24, 1953 (the same day Langston Hughes testified) and faced off against McCarthy’s hatchet man, Roy Cohn, declining to name names. (See: http://todayinclh.com/?event=dashiell-hammett-refuses-to-provide-names-of-contributors.) Call it: “The stuff that nightmares are made of.”

Alcatraz, of course, is most widely known as the federal penitentiary where hardcore criminals like Al Capone, “Machine Gun” Kelly and the “Birdman” did hard time; more to come.

SIDEBAR:

DESTINATIONS:

Alcatraz: https://www.alcatrazislandtickets.com/; https://www.alcatrazhistory.com/factsnfig.htm; https://www.nps.gov/alca/planyourvisit/fees.htm.

French Polynesia: https://tahititourisme.com/.

Pitcairn Island: https://www.visitpitcairn.pn/; https://www.government.pn/.

GETTING THERE:

Aranui: https://www.aranui.com/en/; (800)972-7268.

United Airlines: https://www.united.com; (800)864-8331.

RESTAURANTS:

John’s Grill: https://www.johnsgrill.com/; (415)986-0069.

Delancey Street Restaurant: http://www.delanceystreetfoundation.org/enterrestaurant.php.

HOTELS:

Hilton San Francisco Union Square: https://www.hilton.com/en/hotels/sfofhhh-hilton-san-francisco-union-square/; (415)771-1400; 1-800-HILTONS.

Beacon Hotel: www.beacongrand.com; (866)377-9412.