“By God,” Bush said in triumph, “we’ve kicked the Vietnam syndrome once and for all.”

This was Bush 41, a quarter of a century ago, celebrating the terrific poll numbers his kwik-win war on Iraq was generating. Remember yellow ribbons? I think he had a point. “Vietnam syndrome” — the public aversion to war — still has a shadow presence in America, but it no longer matters.

Our official policy is endless bombing, endless war. No matter how much suffering it causes — over a million dead, maybe as many as two million, in Iraq, Afghanistan and Pakistan — and no matter how poorly it serves any rational objectives, our official response to geopolitical trouble of every sort is to bomb it into compliance with our alleged interests. The cancerous “success” of this policy may be the dominant historical event of the last three decades. Endless war is impervious to debate; it’s impervious to democracy.

Greg Grandin, writing recently at Tom Dispatch about Henry Kissinger’s extraordinary contribution over four decades to Washington’s war-no-matter-what consensus, pinpoints a moment at the onset of Gulf War I that gave me deep pause. In that moment, war had lost its controversy, its raw demand for public sacrifice. Suddenly war was little more than . . . entertainment, as cozily unifying to the American public as professional sports. War and television, you might say, had signed their post-modern peace treaty.

Back in 1969, shortly after Richard Nixon was inaugurated (on a platform that included ending the war in Vietnam), Kissinger and Nixon launched — in deep, dark secrecy — their bombing campaign against Cambodia. This campaign was a war crime of the highest order, devastating and utterly destabilizing Cambodia and creating the preconditions for genocide, as it allowed the Khmer Rouge to come to power.

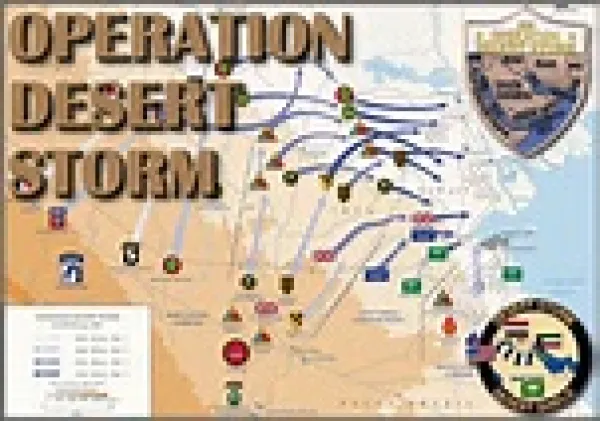

Fast-forward a few decades. Kissinger was no longer in government, but as a high-profile pundit, he was still a major player in American politics, and he pushed the war button at every opportunity. So when Saddam Hussein invaded Kuwait, Kissinger was an early proponent of a military response. Eventually, of course, George H.W. Bush launched Operation Desert Storm.

And Kissinger, wrote Grandin, “was once again a man of the moment. But how expectations had shifted since 1970! When President Bush launched his bombers on January 17, 1991, it was in the full glare of the public eye, recorded for all to see. There was no veil of secrecy and no secret furnaces, burned documents, or counterfeited flight reports. After a four-month-long on-air debate among politicians and pundits, ‘smart bombs’ lit up the sky over Baghdad and Kuwait City as the TV cameras rolled.”

I remember that all too well. I remember the sudden enormous void I felt open up as I watched what might have been the onset of World War III hit the airwaves, knowing that most of the country supported this reckless atrocity.

Grandin goes on: “Featured were new night-vision equipment, real-time satellite communications, and former U.S. commanders ready to narrate the war in the style of football announcers right down to instant replays. ‘In sports-page language,’ said CBS News anchor Dan Rather on the first night of the attack, ‘this . . . it’s not a sport. It’s war. But so far, it’s a blowout.’ . . .

“It would be a techno-display of such apparent omnipotence that President Bush got the kind of mass approval Kissinger and Nixon never dreamed possible. With instant replay came instant gratification, confirmation that the president had the public’s backing. On January 18, only a day into the assault, CBS announced that a new poll ‘indicates extremely strong support for Mr. Bush’s Gulf offensive.’”

There were yellow ribbons around every light pole as Bush proclaimed that “Vietnam syndrome” was dead. All it took was a permanent shift of responsibility away from the public at large — via elimination of the draft — combined with an ultra-sophisticated public relations effort that successfully turned our former ally, Saddam Hussein, into The Face of Evil. The slaughter of 100,000 Iraqis during the month-and-a-half-long Desert Storm was, apparently, a small price to pay for the good we had accomplished, and seemed not to mar the post-invasion celebrations.

And a different kind of syndrome — Gulf War Syndrome, a.k.a., Gulf War Illness — the name for the serious health consequences suffered by American soldiers due to an array of war-related toxic exposures, including ultra-fine depleted uranium dust, was well off in the future at that point, with bureaucratic denial and media indifference destined to minimize its impact on public awareness and forestall a re-emergence of large-scale public anti-militarism.

A decade later, another Bush in office, the Towers go down. George W. proclaims that America will take on Evil itself. And even though his successor, Barack Obama, is swept into office on the global hope for peace, war remains the default setting. Fourteen years in, war does, indeed, look endless. Obama recently announced, for instance, that he won’t be the one to pull U.S. troops out of Afghanistan. War is now, as I say, impervious to democracy, despite the incredible harm — the millions killed directly and indirectly because of the war on terror, 60 million refugees worldwide, numerous countries in chaos — it continues to cause.

Maybe, as scattered individuals, we long for peace, but for now, the interests of war are safely fortified from this longing. As we stand against these interests anyway, let’s declare, as a starting place, our belief that war is never the path to peace.